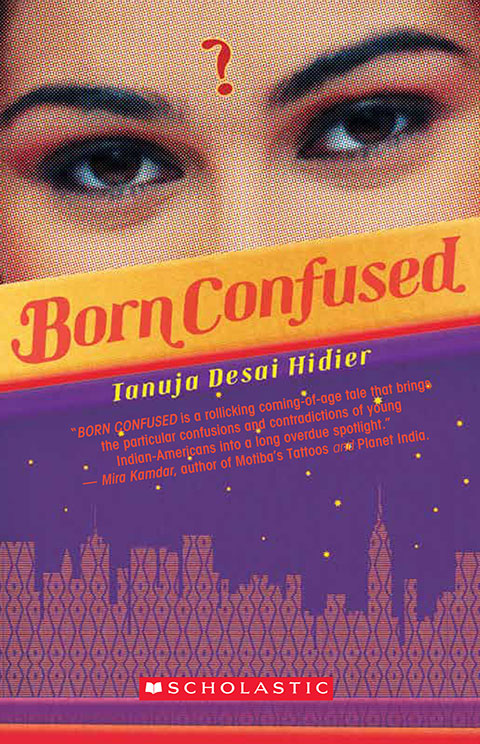

In her debut novel Born Confused (2002), Tanuja Desai Hidier, a talented singer-songwriter and writer based in London, introduced us to Dimple Lala, her 17-year-old Indian-American protagonist from New Jersey.

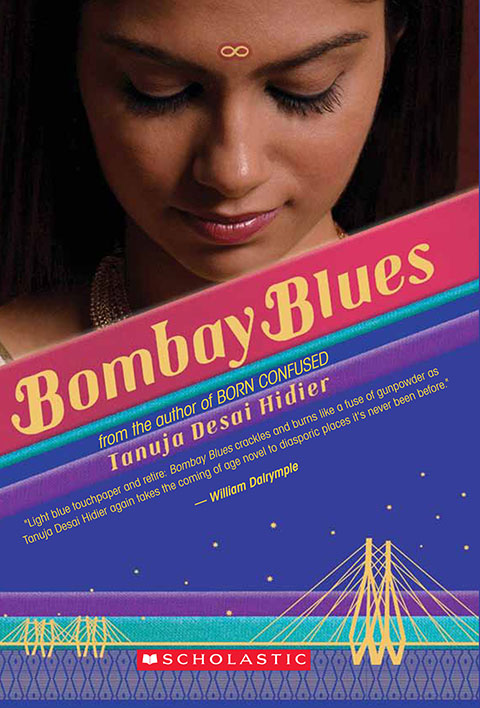

After its release, the novel was hailed by Rolling Stone and Entertainment Weekly as the one of the best young-adult novels of all time. Desai Hidier has recently released Bombay Blues, the sequel to her debut novel, which continues Dimple’s journey as she navigates her way from adolescence to adulthood against the backdrop of a globalised India and the city of Bombay, all the while discovering and blurring boundaries between the modern and the traditional, the self and the other; what it means to be an American and what it means to be Indian.

With thoughtful prose and a captivating stream-of-consciousness narrative, Desai Hidier captures the flavour of a manic and vivacious city like Bombay. There’s a wonderful rhythm to her writing, a musicality and playfulness that makes it a compelling read and a richly layered text. This novel is also accompanied by an album of music titled Bombay Spleen, featuring songs that are inspired from the book.

Read on for excerpts from an exclusive interview with the author—

“With Born Confused I wanted to fill a hole that had been on my childhood bookshelf, with a South Asian-American coming-of-age story.” Photograph by Gaurav Vaz.

You released Born Confused in 2002. Were you expecting the kind of acclaim and success that it received?

I wasn’t expecting a thing! Honestly, writing it was gift enough. I was just so overjoyed to finally have found my story, to be writing ‘the book’ whose unwritten weight had been upon me for so many years, that really the only thing on my mind was getting in that zone, that flow, and remaining there: being absolutely true to my characters and to their journey. Really, with Born Confused I wanted to fill a hole that had been on my childhood bookshelf, with a South Asian-American coming-of-age story. An exploration of ‘brown’. (And, many years after that, one of the reasons I wrote Bombay Blues—an exploration of ‘blue’—was to move beyond the skin.)

I grew up in a small, predominantly white town in western Massachusetts. We were the first ‘brown’ people—South Asians—there, though there were a couple of African-American families. At that time there were no people of our particular colour anywhere: on bookshelves, in bands, on T.V., even forecasting the weather. (Add to that the fact my parents were the first from both sides of the family to immigrate to the U.S.A.) And really, this was my main struggle as a writer: doubting whether I had what it took to write a novel. Utter confusion about what to write, how to express my cultures. In short: not recognising the value of my own story. That, though I’d never fully felt a part of either side of my hyphen—Indian-American—that was a part of being part of it.

The city we live in, as humans, is multiplicity. A hyphen doesn’t have to be a border: it can also be a bridge. (And for me, Bombay Blues is about walking this hyphen, existing on that bridge, not on either side of it.) It may be, in fact, by inhabiting this in-between that we finally ‘arrive’.

And what an incredible experience it’s been to find that Dimple’s story seemed to resonate with so many people once it came out. It was thrilling for me that Born Confused was recognised as the first ever South Asian-American coming-of-age novel, but equally thrilling was hearing from readers from all kinds of backgrounds and ages who’d connected to Dimple Lala’s journey. In fact, I often hear from non-South-Asian readers telling me, “That’s exactly my life… except the food is different!”

What were some of the challenges you faced in getting your work out there?

I actually sold Born Confused on a proposal before having written it. It’s a serendipitous story: I met David Levithan, the man who would become my editor through the violinist in the punk-pop band I was frontwoman in at the time in N.Y.C., when a group of us went to see Fiona Apple play at Roseland. We hit it off, though we didn’t talk books at all that night—just music. A couple of months later, when I knew I was moving to London, I set up a meeting with David at Scholastic to see if I could rustle up some editorial work so I’d have something to do, could hit the ground running in the U.K. I’d been working as a freelance editor/copyeditor in N.Y.C., amongst myriad other ‘day jobs’; I’d also been working on short stories, short films, scripts, music. Unbeknownst to me, David was just about to launch the Push book imprint, and within moments of my arrival, said: “Perfect timing! So what’s your book idea?”

Somehow I knew it wasn’t the moment to say: Um, I just want to proofread someone else’s book. So I told him a truth: ‘Well, I’ve been working on a South Asian-American character’s journey through my short stories and would love to tell that tale in a novel.’ And David said, ‘Well, that’s a book I’d love to help you get on the bookshelf. So get to London. Unpack. And send me a one-page synopsis.’

So I got to London. Unpacked, and unpacked my idea as well: I sent that page. He liked it. And then, a few months later I’d delivered a final proposal that consisted of a twenty-five-page outline of the action (for which I used what I’d learned in a screenplay writing course in terms of structure), about fifty pages of my short stories, and a couple scenes from the proposed book. And Scholastic bought it, which was very exciting. It was a bit unusual to sell a book on a proposal like this, and it helped me immensely to know there was someone out there waiting for it.

What inspired you to write a sequel to Born Confused? For how long have you had it in mind? And why did you choose Bombay as a setting for the novel?

During the decade that passed between both books, I played around with a lot of different ideas for my second novel. I had considered launching right into a sequel when Born Confused came out. But as time went on, I began to think—perhaps even feel a self-imposed pressure—that perhaps I should work with another set of characters the second time around. I had a few different files for next-novel ideas, and a sort of back-burner Word document called ‘BC2’. And though the next-novel files filled up with notes, I began to find that every time I’d get an idea that really sparked something for me, I’d think, ‘Maybe I should save this one for Dimple’. Over time the ‘back-burner’ BC2 file of notes for Dimple grew to nearly 200 pages long! Though I’m not sure a lot of those notes in fact made their way into Bombay Blues, it was pretty clear from the sheer number of them that my heart was still with her.

It’s a funny thing with characters—Dimple is like a friend, a sister, another version, avatar of my journey. But I began to feel a really maternal feeling towards her as well—protective, a little concerned, curious—and just started wondering what she’d been up to, where she was and what was happening with her. And I knew the only way to find out would be to write it.

And Bombay, it became compellingly clear, was where I could—where I wanted to—find her. I longed to write my way towards this metropolis of myth and memory—and, hopefully, into it. And it also felt like a natural next phase for my characters: exploring what would happen if they were transplanted to the supposed motherland—to their art, and their hearts.

To what extent do you think a city shapes one’s identity?

Some of the greatest inspirations for my work are: People. People. People. The dynamics, fireworks, fallouts between them. The joys and the blunders, the pain and the wonders on the route to connections. Cultures, which are, like the people who compose them, ever evolving, ever changing, ever in flux. And cities, as shifting homes of these ever-fluctuating cultures, and yes: most certainly as shapers of identity (and of course, it works both ways: people shape cities too), to the point where I’d say cities are protagonists in my books, too: N.Y.C. in Born Confused, Bombay in Bombay Blues.

Humans have avatars; so do places. In Bombay Blues, Dimple explores Bombay—the place of a personal past, of family history and mythology that she is seeking her own connection with (which I, on my parallel journey, was doing writing it). But she also explores Mumbai—the modern-day metropolis and perhaps a future one too; Unbombay—a fictitious zone that she unexpectedly discovers when she drops the map; less a place, more a mental space about existing in the present flux; a city that exists for that moment, then is gone; and Heptanesia (the before the ‘before’): the earliest documented name for the islands that were Bombay, from the ancient Greek for ‘cluster of seven islands’.

On another level, though many miles away, she forges a different kind of connection and perspective on New York City, too. And, writing her journey, I did, too—and even deepened my connection to London, from where I was writing my and her blues.

We see Dimple grappling with issues pertaining to her cultural identity, her identity as an artist and her sense of self. What were your experiences in dealing with these notions as a writer and a musician?

I think I’d always known I wanted to write, but after a childhood spent in utter faith that this was, therefore, what I would do, insecurity—and endless distraction, a.k.a. N.Y.C.—struck. During my own N.Y.C. years of great highs and lows, endless adventures and eras of confusion (about career, culture, love, life, which subway line to take), I worked several jobs as a copyeditor. I also interned at the literary magazine The Paris Review, hostessed at a Tex Mex restaurant, worked as a secretary in the Whitney Museum’s Film and Video Department, walked a saluki dog (who one day escaped me and sent me on a 100mph chase through Central Park), co-hosted an online streaming music program that vaporised almost overnight when the Internet bubble burst, and promoted parties at a nightclub—all this while collecting course catalogues and contemplating my escape from it all by going to grad school—though I could never figure out for what.

For a fiction writer, it’s all fodder, right? Unfortunately it often seemed to be all fodder, no fiction. I did take some creative writing workshops in N.Y.C., but couldn’t work past several connected stories with a white protagonist who—with very little manoeuvring—turned Indian-American along the way. Similarly, as a kid I used to spend eons inventing band and singer names, designing the album art for these imagined crooners, and sometimes even writing the songs themselves. I had a whole set of index cards where I’d draw these fictitious frontwomen on the front and write out their bios in great detail on the back. Always women. Always frontwomen. And always—all of them—each and every single one: white. Incredible, when I look back on it, that I never ever pictured myself singing the very songs I was writing, even designing the art for.

Funnily, in some ways I got into performing music because I was so scared to do it. The more terrified I was, the deeper my desire went. I tend to be extreme when I finally get around to facing my fears, questions. I was the kind of kid who’d hear a noise in the dead of night, be petrified there was some kind of phantom in the basement boiler closet, and therefore would have to work my shiv-shaking way to that closet, fling it open, and run into it. It was, similarly, a provocative mix of fear and desire that led me to start performing music in front of people.

Inhabiting a song, a story always feels like an opportunity to inhabit, explore another avatar. Sometimes you open a can of worms as well. But then, I guess you’ve got to grow wings and eat them. I’m very interested in avatars of ourselves. I believe reincarnation happens within this lifetime, in a sense—all at once, even. This is a theme in both of my books: life viewed from different angles, life played at manifold tempos. Mixed; montaged; multiple. Constantly shedding and growing new skins. Maybe that’s what reincarnation’s all about: reinvention. And ironically, sometimes we can be most ourself—when we embrace ourselves. In all our contradictions, which are no longer contradictions if we widen, deepen our definitions, our angles, frame, lighting.

Your novel looks at gender, marriage, and sexuality from the point of view of a young woman. How similar/different are the experiences of young women in these areas as compared to young men?

My experience has only been as a woman (thus far!), and is the only one I can speak of from firsthand experience—and it’s been blessed. I’ve been lucky in that I’ve grown up in a family where there’s been a lot of trust and not only open communication but open hearts and minds—so I think I’ve had a lot more freedom in my personal life and with my personal choices than many people have.

But it depends on what you mean. If we’re looking at societal ‘norms’ and expectations, I would venture to say that there are far more double standards, and some extremely, horrifically dangerous ones, placed on women generally. To be ‘feminine’, ‘suitable’, ‘sweet’ (can I scream now?)—to submit. Sit still. Shut up. Be ‘good’. The whole cliché of the Madonna/whore complex—still unfortunately alive and unwell in many parts. These pressures come at all levels of society—yes, even the very educated and supposedly enlightened echelons as well.

These pressures can be on pretty much anyone who doesn’t fit in the ‘box’. But we need to realise: This box simply does not exist! (If it does, it’s a coffin.) We are bigger than boxable, bigger than bannable, bleepable. Human beings and their, our, hearts, cannot be contained in this way. When we try to do this, all those fears, feelings, frustrations, impulses go underground; lead to illness: cultural, personal. Societal. And always, always, must find a way out, a release.

“We, as individuals, as societies, need to activate compassion.” Photograph by Gaurav Vaz.

We see generation gaps and differences in beliefs between parents and their children, through the exchanges between Dimple, Sangita, and Kavita. What, according to you, can be done to overcome these differences?

It’s a tricky one. But communication is the key. Communication within families—and also outside of the home: creating learning environments where people are encouraged to question things, not just swallow belief systems wholesale. Nurturing curiosity. And mutual respect. The youngers for the elders—but the elders for our youth as well. I’m very lucky in that my family were and are absolutely my support pillars. They’ve always encouraged me, and even better, had faith in me—even when, for many years, I had none in myself.

I think part of the reason for this is—well, it’s just who they are. Very compassionate and open people. Also, the lines of communication were always open between my parents and me growing up; I think this removed any potential ‘shock’ element, as we had a dialogue going all along the way, so any kind of changes/developments happened gradually, organically.

My parents had dealt with opposition in their own time as well: They met in medical school in Parel, and married out of caste, had a love marriage, which was quite a bit of a scandal in my father’s Gujarati village. My mother also was one of the few women in medical school at the time. And then they were the first from either side of the family to emigrate to the U.S.A. So they’d already been living, thinking, colouring outside the lines. They were the pilgrims, the founding mother and father of our family in the New World.

We, as individuals, as societies, need to activate compassion. And to be willing to step into another set of shoes and observe that person’s experience, with heart. Tradition and ‘modernity’ can still find a meeting ground—but one has to be open, as with a story, to revising, rewriting. People, relationships, cultures are always evolving. Some traditions may need to as well—especially those that are inherently unhealthy, detrimental, founded on the devaluation of some members of the very society practising them.

Art, storytelling can help immensely in this process. Writing, imagining things into reality. If you can’t have a direct conversation—maybe there is a story, a character out there who can help you have it. Make the first move.

Both your books have soundtracks accompanying them. Had you always planned on doing this? How did the idea of booktracks come to you?

Music (and songwriting) and books (and fiction/poetry writing) have been a major part of my life since I was a child. And as an adult, I played in bands for many years, in New York and also in London. When I lived in New York I was the frontwoman in a punk-pop band, io. When I moved to London, I joined the band San Transisto. I’ve also made a couple of short films, which perhaps tuned me in to the idea of making soundtracks, albeit on a smaller scale.

And music is a main theme in both my books: how it brings people together, as a universal language, as well as the way it transforms with culture and chronos, moves its grooves with the diaspora. It’s also what some of the characters actually do and are pursuing (both novels are populated with DJs, musicians, producers, nightclubs, live music). So it felt like a natural progression.

With Born Confused, I made my first ‘booktrack’ album of accompanying songs, When We Were Twins, though this was two years after Born Confused released. The album was featured in Wired for being the first ever ‘booktrack’—exciting! With Bombay Spleen, the book and album-writing process were simultaneous and thoroughly intertwined. It took me three years to complete both—and they were literally finished within days of each other, during a very hectic April in N.Y.C. I’d often be in the studio in Brooklyn with producer Dave Sharma all day, and then doing my final edits on the book all night.

For me, Bombay Blues and Bombay Spleen are part and parcel of the same project—different media for exploring the same story. Bombay Blues is my prose poem to Bombay; Bombay Spleen is the sonic part of this same tale (the title is a reference to Baudelaire’s Paris Spleen, which heroine Dimple Lala is reading when the story opens). The prose and songs developed organically side by side; I don’t recall it being an overly thought out decision so much as a natural way for me to explore and express the story.

Interestingly, during the process I realised that the narrator of the songs is not quite the narrator in the books. They’re like sisters on parallel journeys. Sororal twins. Unidentical. So that was the idea behind the structure of the album, though the songs evolved, of course (like the book!) out of order and over time.

What are your views on the representations of gender, race, and culture in popular culture?

Well, as long as the question has to be asked—and it does—we’ve still got a way to go. That said, certainly ‘progress’ has been made, in that a greater diversity of representations are making themselves felt in pop culture, especially relative to my growing-up years. This isn’t an entirely new phenomenon. Some of the musicians, for example, who I find to be the most inspiring, have been testing conventional notions of gender and sexuality for years now (David Bowie, Patti Smith).

In literature, certainly, there are voices from a more diverse range of backgrounds being heard now (in the U.S., for example, see the buzz #WeNeedDiverseBooks has engendered). Which is wonderful, because we obviously need as many voices from as many backgrounds as possible to approximate a kind of ‘truth’—to represent the roundness of a cultural, or any, experience. Also as a more diverse group of ‘storytellers’ enters positions of power—which is happening—pop culture representations of gender and race are shifting (for example, in the TV/film area, Mindy Kaling, Lena Dunham, Tina Fey).

This is a key to change in pop culture. We need to take authority for our voices, tell our stories ourselves. We must reveal and revel in our multidimensional selves—and share them with the world, if we can. Our stories are our arsenal, our fuel, our example: of other ways to be, alternatives that could, perhaps should be norms. We’re a powerful chorus when we bring our voices together. When we make ourselves heard.

Finding one’s voice can take time. I know this from experience. But I also know it can be done, and is vital work.

Where does the term ‘American Born Confused Desi’ stand at the present moment, in a globalised world?

At the time of writing Born Confused, I think that particular type of cultural confusion—the hyphenated identity diasporic sort—was likely more prevalent among those of us who were living outside the country of our cultural origin. We were first-generation Americans. Our parents were, in a sense, the founding mothers and fathers of this iteration of the diaspora. And as we came of age, we had to create a language to express this evolution as well (through literature, music, etc.). This takes time.

When I was living in New York in the late ’90s I heard this term A.B.C.D. bandied about quite a bit. But it was in the process of becoming outdated even then. The late ’90s was an incredible moment in terms of the subculture’s gaining of critical mass and momentum: we witnessed the birth of South Asian Studies departments, South Asian Student, Journalist, Lesbian and Gay associations, parties such as DJ Rekha’s Basement Bhangra and Mutiny, South Asian film festivals, and more. At the same time, mainstream culture was adopting (some would argue co-opting) many aspects of South Asian culture: Gwen Stefani in the bindi, Madonna’s yoga period, and so on.

Part of what I wanted to do in Born Confused is turn the ‘C’ for Confused into one for Creative in the moniker ‘American Born Confused Desi’—as this seemed to more accurately reflect the desis that peopled this world I’d known in N.Y.C. Today, in many ways, the culture has ingested and journeyed past that musical moment and all the diasporic paths it drew together. And with Bombay Blues—written a decade after Born Confused—I suppose I was less concerned with identity in strictly cultural terms. I wasn’t even really thinking about ‘confused desis’; on a personal level, writing Born Confused resolved that question for me.

———

Click here to visit Tanuja Desai Hidier’s official website. You can watch the video for ‘Heptanesia’ from Bombay Spleen at this location.