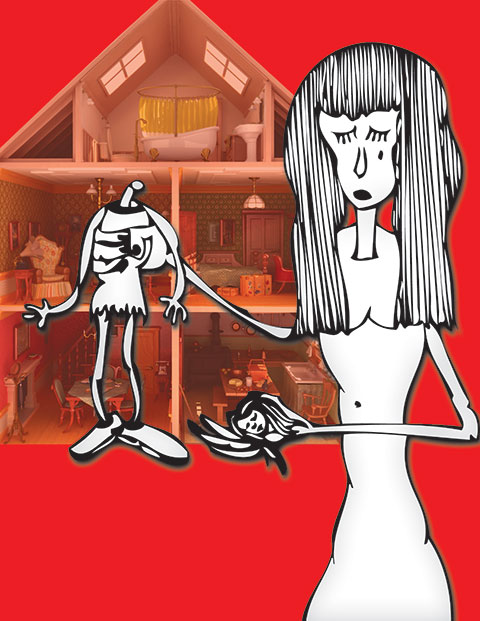

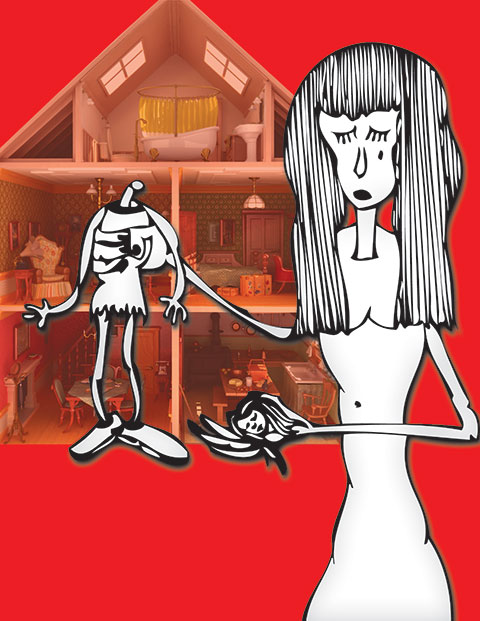

Florie’s head has rolled under the sink, her torso is slumped against the wall. One of her legs is in the bathtub, the other clogs the toilet. She has a calm and detached expression on her face; she seems unaware that her head is not where it should be. The bathroom curtains are open. Dust motes float down the hollow cavity of her neck. Her joints are stiff, but it’s nothing to worry about. It’s her natural condition.

The sink over her head is the size of a lemon. Around the sink: shampoos the size of thumbtacks; a bar of soap the size of a pill; a glass the size of a needle, in it a toothbrush the size of a nail. The bathtub is about as big as a bar of soap. The tiled bathroom floor is the size of a notebook, and the whole dollhouse sits with its back against the wall facing the girl’s bed. It’s the first thing she sees every morning.

The girl yawns and rubs her eyes, stretches her limbs and sits up on the bed, and upon witnessing Florie’s condition, she sighs. It had scared her the first few times. She had yelled, and he had been delighted. But by now, she’s used to it. She climbs out of bed, walks over to the dollhouse, and bends to gather Florie’s remains. There’s no point trying to put her back together. He’s always quite thorough.

She lightly kisses Florie’s plastic lips, then descends the stairwell and tiptoes past the kitchen, her footsteps masked by the clatter of plates, the sizzling of the stove, the faint hissing of the radio. She pushes through the backdoor and walks out of the back porch to a slight protrusion of fresh earth at the far end of the plot. She digs into the earth with bare palms, digs till she’s made a trench the size of Florie. The boot and ankle of one of his former victims pokes out. With her thumb, she pushes it down till it can no longer be seen. She puts down what’s left of Florie in the middle of the trench and arranges the parts in the right order: the arms, legs, and head go where they should be. She bends to kiss Florie’s plastic lips for the last time and begins to cover the trench.

She hears the squeaking of sandals; she doesn’t have to look up to know who it is.

“She screamed a lot, this one,” says a tinny, 12-year-old voice. “That’s why I went for the head first.”

She stands and turns around.

“She still screamed after that. She screamed when I pulled her arms out, when I pulled her legs out.”

His eyes are alight and his lips are stretched into a wide, shit-eating grin.

“Are you gonna miss her?”

Her fingers curl up into a fist. He walks a step past her and she feels something lurch within her stomach. She knows what happens next. He’s so predictable. It’s almost ritualistic, and yet, it gets to her every time. She hears him pull down his zipper, then the sound of piss splattering against earth. She counts numbers in her head. He pulls up his zipper at eleven.

“That way she doesn’t have to go thirsty.”

Nails dig into skin. Something moist accumulates at the bottom of her eyes.

“Next time, I’m gonna give her something to eat.”

In her mind’s eye, she sees his head under the sink, his torso slumped against the wall.

“Are you two fighting again?” bellows the mother from the back porch. “Come inside and have your breakfast, you’ll be late for school.”

“Coming, mom,” he shouts. “I’ll give her something to eat,” he says again, and beaming, he runs into the house.

She wipes a tear and turns to look at the piss-wet earth glistening in the sun.

“I’m sorry,” she says.

* * *

“You can ask anyone you like. You can ask Kapil, Aniket, Ajinkya, anyone from my class. You can ask Rathod Sir himself if you want. I scored the most goals at the tryouts. I scored more goals than anyone else. Hands down, I was the best player who tried out. But the fucking bastard—“

Fist meets table. The plates rattle.

“I won’t tolerate such language in my house,” says father.

A moment of silence. The toaster goes ting.

“I can fucking say what I fucking want! You can’t fucking stop me from fucking saying what I fucking want!”

The mother walks over with a plate of toast and sets it down on the table.

“It’s the films he watches,” she says. “And the music he listens to.”

“Fuck your films and fuck your music! It’s fucking you who’s…”

The father takes a deep breath, sighs, pictures the neighbours sniggering and realises just how badly he doesn’t want to situation to escalate.

“Calm down, son,” he says. “You don’t want the neighbours to hear, do you?”

“I don’t care if the fucking neighbours hear! I don’t care if the whole fucking world hears! No one fucking understands me anyway!”

Again, the fist. This time, the silence persists.

“You will calm down, lower your voice, apologise to your mother, sit down quietly, and finish your breakfast. Then you will tell me what’s bothering you.”

He lowers his head, mutters something under his breath.

“Be quiet. And finish your breakfast.”

His face grows redder in degrees.

“Fuck you! None of you understand me!” He storms out of the kitchen.

“Son, son, where are you going?” yells the mother and runs after him.

The father finally looks at the girl. The second time was a mistake, he says to himself. I shouldn’t have let my self be pressured. This one turned out just right. Or did she? She’s eating toast unbuttered. When was the last time she actually opened her mouth?

“What’s the matter, kid? Here, you want some butter to go with that?”

He passes the butter. She ignores it, takes another bite.

“What’s wrong? He’s breaking your dolls again?”

She nods, looks away.

“Well… I could tell him to stop, but when has that ever worked?”

He gestures in the general direction of the sounds trickling in from outside. Neither of them can listen to the conversation, but they can tell what it’s about.

She shrugs.

“And aren’t you too old to be playing with dolls anyway?”

She wrinkles her nose.

“Alright, alright,” he chuckles and pats her shoulder. “To each his own, I guess.”

He takes a long sip of his coffee. “What a horrible way to start the day,” he says. “And the clincher? It’s going to get worse. Your grandmother’s coming.”

He sees her shudder and laughs.

“Oh, come on! She’s not that bad. There’s a reason why your brother turned out this way, there’s a reason why your mother think’s the sales meeting ends at 10 when it actually ends at 6, but she’s not that bad.”

She looks away.

“Yeah, you’re right. Who am I kidding?”

* * *

The teacher is talking about atoms. The words float about around her, but she can’t tell them apart. She’s zoning out. She tries to concentrate on what the teacher is saying, but his monotonous drawl makes it so much harder to stay awake. She leans back, closes her eyes, gives in. Soon, she’s in a tub, naked. There’s a certain coldness rubbing against her thighs. She looks down and sees her legs intertwined with another pair. What she feels against her skin isn’t flesh. Far from it, it’s synthetic and glistening, like plastic. The legs end at a mound. Above the mound: a flat plastic stomach, breasts without nipples, a face she recognises. It had rolled under the sink just the night before.

“People can be mean, yes?” she hears. “We give them hands and look what they do with them.”

Florie’s lips remain sealed, but the girl can hear the sounds in her head. She opens her mouth to talk, then realises she doesn’t have to.

Florie understands.

“Don’t worry child. He’ll learn his lesson. They all do.”

* * *

She climbs out of the school bus. As she’s walking through the foyer, she hears something break. Inside, the mother is shrieking, and she can hear something thumping against the floor. The sounds come muffled through the door. She rings the doorbell.

“I’ll get it,” says a twangy voice. It reminds her of her brother. Two clicks and the door swings open.

“What took you so long?” says the grandmother. “You aren’t going around with boys, are you?”

She shakes her head.

“God knows what she does. Never opens her mouth, that girl,” says the grandmother in a lowered voice, as if to herself. “That doesn’t matter. What matters is that you’re here. Give your granny a big hug.” And she locks her into a fierce bodylock, knocking the air out of her lungs.

Beyond the grandmother’s shoulder, she can see him running along the back of the sofa, bouncing a ball the size of Florie’s head against the floor, the ceiling, the walls. The mother is running behind him, shouting, “Son, stop! Stop already! Do you really want to see your mother cry?”

The grandmother lets her go, and just before she’s about to say something uncomfortable, the mother grabs her arm and says, “Mother, why don’t you say something? He never listens to me, but he listens to you.”

“Let him play! Look at him! So happy and energetic. Why do you want to clamp him down? You don’t want him to end up like you, do you? You and your books. You wasted your entire childhood locked in your ro—”

“For god’s sake, mother. Now is not the time.”

“That’s what you’ve been saying all your life! And look where that’s got you.”

“For god’s sake, mother,” the boy mocks from the other end of the room. He throws the ball hard against a shelf. It knocks a vase out of balance. It hits the ground and shatters.

The grandmother guffaws.

“For god’s sake, mother.”

Sniggering, he begins to climb the stairs, bouncing the ball off each subsequent step.

“Son! Son! Don’t go up there!”

She follows him up the stairs.

“So,” says the grandmother, holding her shoulders. “How has my granddaughter been? Has she learned to talk yet?”

She nods. Her grandmother opens her mouth to speak, but she’s cut short by an enormous thud and the sound of wood splintering. She feels something twist in her chest. It can’t be. He couldn’t have.

She shoves her grandmother aside and, ignoring her cries, rushes up the stairs, skipping every alternate step.

“I SAID STOP IT!” She hears her mother’s climactic banshee shriek. It comes from within her room. No. He wouldn’t dare. She turns the corner, sees the door open, and hurries in, seeing that her fears have materialised. The ball has torn through the kitchen of the dollhouse, taking the table and all the counters with it. It has ripped a hole right through the faux-wood floor and disappeared within it.

“Where did the damn thing go?” he says.

He bends and reaches for the ball inside the hole. His hands disappear into the darkness.

“FUCK!” he shrieks. He has never managed to be so loud, even at the breakfast table. She can see the agony on his face. Despite her dismay, she cracks a smile. She knows that when he pulls his hands out, they won’t be the same.

Not again.

Not anymore.