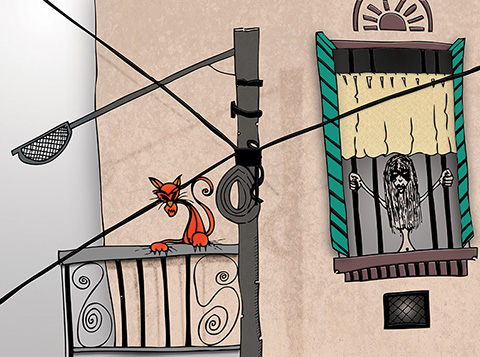

A school day gets over. Children mill around the area, with their parents in tow. Mini buses and other public vehicles clog the road, while aloo kabli vendors and puchkawalas and cotton candy sellers jostle with soft drink and ice cream carts. I stand at the tree across the road and stare up at the old house facing the skyscraper. A woman stands at the window grill, naked.

(It is a bathroom window. I know, because I have seen this several times before—the plasticity of the slightly raised curtain and its occasional wetness, the constant nakedness of the figure which is always there, in the same pose, every day. Her hands on the grill, breasts resting on the sill, almost breathless, as if about to take flight.)

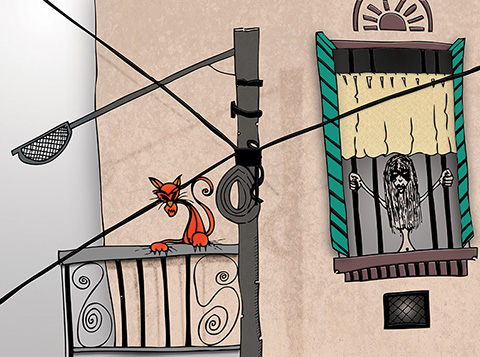

I sketch her from memory, a shadowy, faceless woman; her nakedness strangely un-sexy, almost absurd in its banality. How do I know she’s naked? I cannot see her beyond a silhouette, a mere shadow, flitting almost wraith-like against the window grill. And yet, I know her. Intimately. There is something intense about that still posture, delicately balanced (on her toes?) and yet pressing in its urgent reaching out to the world. Who lives there, in that house? One day I saw a cat stretch out on the balcony, just beyond that window, almost reaching out to her, almost as if it were familiar, her own kin. Her only kin, perhaps?

No, of course there is a family. There almost always is, in these mildewed city paras, sheltered by the ubiquitous mishti shops and the grocers and the gallis with their specialist reporters. And yet I have never seen anyone in all these days that I have been watching. The blinds stay down on the balcony, the only other part of the floor that is visible from the road. I watch the house. There is a mandap beyond the main building, but within the larger complex, overgrown with weeds and an abnormally large shiuli tree. I can imagine the annual Durga Puja festivities in full flow in the good old days. People come and go from this part of the house. Derelict, but alive. But is it connected to her? I cannot tell.

Why is it that no one else sees her? Downstairs, a semi-blind watchman has turned up a few times, casting a curious eye on me as he rubs his khaini into his palm. He is accompanied by an obese Dachshund that pants breathlessly in the summer humidity and obscenely wraps its over-long body around his aged legs. I have sometimes had a strong urge to speak to him about her, ask him who she is. But something about her raised arm, the tilt of the head that sometimes rests on her arm, stops me. I feel her despair, a few hundred feet away. It reaches out to me in surges of passionate appeal. She knows I am outside. She must have seen me, felt my eyes on her. Or is she so insulated that she sees nothing but her own pain as she clutches the grill so urgently? Her intensity is what attracts me to her, watching, relentlessly, day after day, yet unable somehow to close the gap that separates us. I write poems to her on Facebook, imagining that she reads them and smiles, perhaps, to herself? What does her smile look like? Does she have crooked teeth like me? Do her eyes crinkle up when she smiles? So many times I have thought of getting my binoculars. All the better to see her with. And yet I’ve been afraid to use them. I carry them now, rubbing them with the diligence of a serial watcher, yet quite unable to actually raise them to my eyes and let the world know that I’m watching.

Today I notice a slight difference. But what? Her hands? Both raised, but only one holds the grill. Loosely. There is none of the regular urgency in her slight swaying movement. Something seems to be trickling down her arm. Goose pimples rise on my arm, and the hair on my nape stands at attention. Has she seen me? Has she, perhaps, in all the time I’ve watched her, watched me too? And has she chosen this day of all days to paint me? Is she, perhaps, a nudist? Is she so lonely that her nakedness has ceased to matter—to her or to anyone else? A glint of metal. She sways, again. She opens her mouth, and throws back her head, gripping the grill with one hand. The free hand rises, strokes her neck. A single line appears across it. Almost in slow motion, she straightens up and looks out again. She stares straight at me. I know she sees me, because she smiles. Then she raises her hand in a slow wave. Almost featherlike, she floats down below my line of vision. Her hand follows, clutching at the air left behind.

Tring! A cycle rickshaw passes, blocking my view. Bile rises up my throat. I stare, frozen.