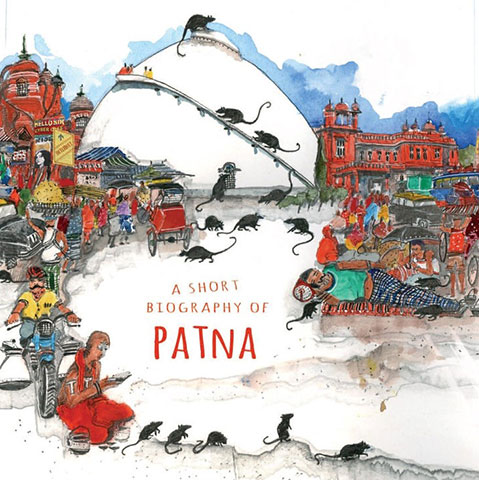

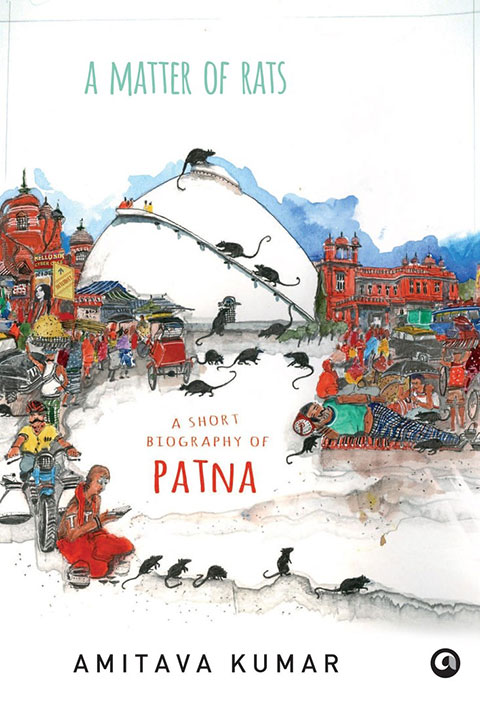

Amitava Kumar’s recently released biography of Patna opens with a lurid account of rats in the city: they are voracious hunters of the night, debauched drunkards, destroyers of crops, thieves of grains, and despoilers of libraries.

These residents of the chthonic city pay nocturnal visits to the surface to forage upon the city’s resources and bloat up to be as “big as cats”. Once, while Kumar was watching television at night during a visit to his parents’ house in Patna, they teetered into the dining room like “stout ladies, on tiny heels, on their way to the market”. They even stole his mother’s dentures.

In this opening chapter, Kumar sets himself up as a literary Pied Piper seducing Patna’s multifarious rats out of closets everywhere. Their presence seems malignant and reminded me of Hieronymous Bosch’s nightmarish paintings of hell littered with chimerical monsters, each of which inevitably had a rat’s face, sharp teeth, and stiff whiskers. Is Kumar trying to say that Patna is a hellish city on the verge of decay? It’s clear from the beginning that the rat is the leitmotif that Kumar uses to express Patna’s reality as a city of nightmarish squalour. But he soon expands the symbol: Patna is not only haunted by these visceral, ever-present, and pesky rats, but also by the absent, escapist rats that have deserted it. The decay is caused by the deserters as much as the insiders. And Kumar himself belongs to the former category. Through a single sentence, he transposes the ratty characteristics upon himself and ascribes the noble characteristics of loyalty and resilience to these primitive creatures. He writes, “I have some admiration for the rat that, unlike me, hasn’t fled Patna and has found it possible to live and thrive there. Oh biradar, who is the rat now?”

Amitava Kumar’s A Matter of Rats

It seems as though Kumar’s sympathies lie with these rats that have stayed behind. Even their gluttony and destructive nature is explained as a biological compulsion: “If it doesn’t cut with those night and day, those teeth will go right through its head.” For Kumar their constant biting reflects their industriousness and survival strategies in the face of adversity, and here these rats become the metaphor for the all the citizens living in Patna. You sense a gossamer of guilt or a certain ruefulness within the author for his desertion, but the knowledge that this city of his childhood would not have been able to contain him is stronger and firmer than this guilt. He writes about his shame and rejection of Patna when he was younger: “I told stories about Patna because they were a part of my shame at having come from nowhere.” More recently, Patna has been reduced to a locus of his parents’ mortality and old age. When he lands in Patna, on a visit from New York where he lives, his only preoccupation is to “see how much older my parents look.”

While he has been away, Patna has plunged further into lawlessness, corruption, political instability, and cultural poverty. There have been various negative stereotypes about the city, targeting its language, corruption, and the belligerence and macho-ism of its people. Meanwhile Kumar himself has been prolifically writing about other parts of the world; his last book A Foreigner Carrying in the Crook of His Arm a Tiny Bomb was about the American war on terror. This physical and creative distance from his homeland makes him distant from these clichés in this collection of stories dealing with themes of history, migration, representation, and love. He neither gets defensive nor dodges the prejudices in the book; rather he reminds one of what existed, excavates what is lost, and shows what still is. This wistful mood is set at the outset through quotes from writer Upamanyu Chatterjee and poet Shrikant Verma that reflect the fatality, loss, and memory of the buried time. And despite the emotions that bind this collection of stories, Kumar’s prose is never elegiac. There is always humour, love, and the possibility of redemption.

Pride reflects from his discussion of Patna’s history as a city of prominence in the chapter titled Patliputra. It includes some interesting information about how the Greek ambassador to Patliputra, Megasthenes, claimed that people left their houses unlocked, and the Chinese monk Fa-Hien noted that the Sanskrit word for Patna meant “the city of flowers”. For a while, Kumar wallows in past glory before a reality check is brought upon by a visit to Qila House, a museum in Patna that supposedly houses Napoleon’s four-poster bed. His excitement is shattered at finding the bed in shambles. The cloth hanging from the canopy is in tatters like “a widow’s veil forgotten in a theatre closet”. The collection of nearly ten thousand artefacts in the museum is a mish-mash and includes Marie Antoinette’s china, Birbal’s silver plates, and a Crown Derby dinner set designed for King George III. The contextual tactility and sensuousness of the lived past is reduced to these deracinated, dead objects housed in a museum “with rain-stained walls and windows that overlooked the brown waters of the Ganga”.

This reduction of the city’s past into scant, leftover objects, and its degradation has become a reason for Patna’s degeneration. Objects as well as ideas suffer from this malady. The city experiences the continuous, protracted failure of a body in its many organs: its archive, its monuments, and its stories. The worst part is that there is nobody to record these many deaths, to record what Walter Benjamin called, the “fecundity of decomposition”. In one anecdote, Kumar remembers a rat as the destructor of his pet parrot. In this way, Kumar has encoded one of the most poignant decays of Patna: the death of storytelling and its representation in stories. Parrots are symbols of sophisticated storytellers; by making rats destroy parrots, Kumar has symbolically represented the triumph of opportunism over creativity in Patna. It is not for nothing that he rues the mushrooming of coaching centres in Patna even though he adulates the effort of one of the teachers. As a result of these centres, real education that is supposed to open consciousness and imagination has given way to tailor-made, restricted studies hinged upon competitive exams. Patna has turned into a wasteland without an oasis of stories. Kumar addresses this aridity in a chapter titled Patna in a Hole.

By writing this book, Kumar has tried to fill this hole. Through this exercise he has fallen in with artists like Subodh Gupta, the elsewhere rat, who keeps the memory of Patna alive through creative processes (Kumar mentions Gupta in his division of Patna into three categories: Patna as a magnet for people from other places to enter in to, the Patna of the original inhabitants, and the Patna of elsewhere, inhabited by people who have left the city). Both Gupta and Kumar reproduce their memories of Patna as forms of art. While Gupta has remade the utensils of his mother’s kitchen and recreated the rituals for hungry gods in huge steel-pot, Wagnerian installations, Kumar has rewritten a biography of his hometown. In Kumar’s case, the memory is sociological and historical rather than personal, which causes a textual thinness—the only grouse that I have with this book.

It is when the personal memories, histories, landscapes, and stories of people coagulate that the thickness and density of a city emerges. In the book, Kumar talks about historical memory but is silent about his own personal memory. We know that he felt shame but he never talks about why and when he felt this shame, the events associated with it, or how (and if) he got over them. (Surely reading Ian Jack’s representation of Biharis in Granta could not have been that epiphanic moment?) Besides, it is difficult to imagine the city without the description of its physical ingredients: its food, markets, and streets. I could not help thinking about Ernest Hemingway’s The Moveable Feast in which he gives a vivid account of Paris through his walk along the Seine or his relationship with his wife and other writers like Gertrude Stein and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Closer home, Vishwanath Mukherjee wrote a book called Bana Rahe Benaras in which he tells stories about the staircases, alleys, houses, and even the bulls of Benaras.

Kumar has told the story of the city through the lives of its people and he has done it well, especially the stories about the coaching institute teacher Anand, who coined the phrase “meouw meow English”, and the love story of poet-postman Raghav. Ultimately, however, reading A Matter of Rats is like experiencing a frisson instead of an actual touch; encountering a beautiful spectre rather than a living person.

[Aleph Book Company; ISBN 9789382277224]