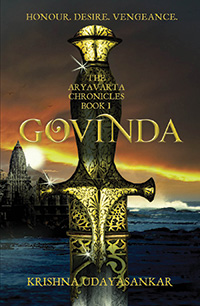

Krishna Udayasankar is a full-time lecturer living in Singapore. Her novel Govinda is the first of an intended three books in The Aryavarta Chronicles. As fast-paced as it is educative, Govinda is a labour of intensive research and passion and has a refreshingly in-depth approach to its characters, otherwise familiar to most of us, from Indian mythology.

We sat down in conversation with the first-time author about the consequences and risks of writing on revered Indian texts, Govinda’s place in the newly emerging genres of Indian writing in English and making the time to write while holding down a full-time job on the side.

“I’d place my faith in the story, in its logical integrity any day.”

It is made clear right at the outset that Govinda (part one of The Aryavarta Chronicles) is not a retelling or reinterpretation. What genre would you say The Aryavarta Chronicles belong to?

When I started work on The Aryavarta Chronicles, I did not have a genre in mind—just the aim of telling a story as best as I could. In retrospect, though, I would personally classify Govinda as alternative history or mytho-history, because it tries to reconstruct the story world of the time along different parameters, the most notable one being that everything needs a rational explanation that precludes magic or superpowers of any form. Having said that, particularly for this book, genre labels have turned out to be rather confusing, if not constraining. I’ve had people who typically enjoy fantasy or science fiction say they love the book despite the complete absence of fantastic or magical elements. Others have liked it simply for the writing and style, which I suppose puts this book in the literary fiction category. At the end of the day, I just want it to be remembered as a good book—the genre is not that important.

In the last couple of years, especially, we’ve seen publishers go out on a limb more often with new genres. Do you think if you wrote this book, say, 10 years ago, you’d have gotten it published?

Call it my ego, but I’d like to believe, yes. The reasons being twofold—(a) this genre is not really as new as we think—there is a rich and longstanding legacy of this kind of work, both in English and in vernacular languages, and (b) good writing has always had a market, irrespective of the genre of the content. I’d place my faith in the story, in its logical integrity any day.

Do you have a favourite character in Govinda?

Yes (grins). I am a huge fan of Shikandin. Not only because he has been a character who has emerged as someone very different from common perceptions, but also because I really like the kind of person he turns out to be—loyal, decent and rock solid—not to mention [that he’s] a guy with a quiet but potent sense of humour. He’s the kind of friend I’d love to sit down and have a beer with.

Govinda does a really good job of introducing readers to stories from our mythology without compromising on the ongoing narrative. You’ve had to factor in both kinds of readers, those who are well-versed with our mythological/philosophical texts and those who are entirely new to it. Were you aware of having to cater to both these audiences while writing? Does that become an added pressure, to make sure everyone is on the same page?

Thanks; I’m glad you feel that the book does a good job of balancing these two aspects. I probably was aware of the fact that there may a diverse audience, but I’m not sure I was trying to cater to either or both categories of people.

In retrospect, I feel there are layers to the story; layers that have crept in as my own (still-limited) understanding of the narrative grew. I suspect these layers are what extend the appeal of the book, despite varying levels of familiarity readers may have with the tale. Also, my aim was to get at the history behind what has subsequently been aggrandised into mythology and used to legitimise or justify today’s social structures and norms. The resultant story of a time of socio-political revolution and change in the status quo is a fundamentally interesting premise used in many genres, including even fantasy! The epic is precisely that—an epic—and such stories have a universal appeal.

It was refreshing to come across such well-developed characters in Govinda. How did you grapple with giving life to characters that have become so reified in our mythology? Were you ever afraid of perhaps transgressing this sort of code we tend to have for mythological figures?

No, not afraid, but both thrilled and humbled (and thanks again for enjoying that part of it!) But to go on, a book like this has a life of its own; the story is way, way bigger than I am. I have tried to let characters move through the storyframe and take decisions that are consistent with their role in the larger narrative—that kind of logical consistency is very important to me. I also believe strongly that these characters are no less heroic for being human beings—a faith that I have learnt from the protagonist of the book, in fact! At the end of it all, I place my trust in the integrity and timelessness of a story such as this—a story about men and women who grow to become heroes in extraordinary times. I don’t mean to be provocative, but if codes need to be transgressed to celebrate this spirit of humanity, then I’m glad to do my little part.

What made you take the plunge into writing? You mention having been a fascinated reader of mythologies and Indian history in your book. When a reader becomes a writer, what changes? Or have you essentially seen yourself as a writer first?

I love writing and have been putting pen to paper and creating imaginary worlds in my head since childhood. In retrospect, when I look at the kind of careers I chose—law and then academia—I can see the thread of logic, the attempt to complement my love for writing with the issues and ideas that I found fascinating, such as the history and philosophy of the complex socio-economic world around us. So when I finally got down to writing, I think all these different passions finally came together. To get a bit dramatic, it was as if all of life’s experiences had been geared towards that one thing.

In terms of the reader-writer transition: I have been, and remain first, a reader. But I honestly believe that every reader is a writer, in the sense that the creativity a reader brings to a book equals, if not exceeds, what a writer puts into it. I firmly believe that writing is only half of the creative process—the other half happens when people read what is written and recreate it in their heads. That’s probably why wordsmithy—the craft of writing—is important to me as reader and writer both, and it ought to be compromised for the sake of an exciting story. Conversely, I also believe that a well-written, literary kind of book does not have to be inaccessible.

What was your writing/ideating process while coming up with The Aryavarta Chronicles? Did you know exactly how the books would be divided in the upcoming series when you first hit upon the idea?

Nope! No clue whatsoever! For me the whole writing process begins around a scene, a moment in the story around which the whole world converges. I try to begin by putting that down, finding its place in a large plot by answering the questions that it suggests: who are these people, why are they here, etc. After that, at some point, the story writes itself, following an internal logical consistency. In fact, when I began, I had the one book in mind—look at where we are now!

In your acknowledgements, you mention the idea of a writer essentially being a “resident of another universe”. How important is this space, physical and mental for writing, to you? More importantly, how did you manage to find that space to write, along with being a lecturer?

My ‘alternative universe’ is pretty important to me, and if it weren’t for my family, I doubt I’d ever resurface, or even want to. I’m very much your dorky, reclusive writer, so I tend to live in my head most of the time. The space is very important for me, mentally, but I have somehow managed to compress the physical space part of it—I could be anywhere, on a bus, walking down a road, sitting in front of the T.V. But my mind is in Aryavarta or some other such place.

Being a lecturer—I teach international business environments—complements my writing, I find. In fact, talking about some of the things that come up during class—democracy, capitalism, international trade, and political relations—all of these give me the grounding to approach my books the way I do, as stories of socio-political change.

“I do fear visibility as an author will change me a person, and I’m not ready for

that at all.”

Between conceptualisation of the series and the actual book release, were there any moments that stand out to you? Instances perhaps where it all got too overwhelming, given the sheer volume of work and opinion already out on the subject.

Oh yes! The amount of material that is out there—both popular and scholarly—which deals with the epic and the epic ages both is simply astounding. Consequently, it did take a lot of research and many months of painstaking work trying to reconcile legend with logic and scholarly evidence and variations in English and vernacular literature across India and other parts of Asia too. As someone trained in social sciences research, I have tried my best to bring that strength to the books when coming to conclusions on why or how things happened in a particular way.

Sometimes, when I find that research corroborates my plot-based construction of what I think may have happened or even opens new doors altogether, it is a soaring-to-seventh-heaven moment. There are also equally impassioned moments of self-doubt: I find it particularly difficult to deal with the sense of guilt, the haunting thought that I have not done right by my story, my characters; that I have not given it my best.

The only thing to do at all these times is to remind myself that a story like this is way larger than I am, that it writes itself. I am but an instrument.

Do you look up reader reviews and comments on websites? At the end of the day, whether good or bad, a novel is a product of painstaking labour, and deeply personal for any author. How do you then prepare to deal with this newfangled online world where anonymity gives way to opinions that can be rather hurtful, if not damaging?

Eeks! How did you know? Alright; I shall confess I do! I try not to do it too often, though, and am learning, but…

One of the best things that could have happened to me (in hindsight) was that the very first review I got (from a reader, by the way) was dismissive and completely negative (smiles). But the good thing is, after a couple of days of agonising and feeling sorry for myself (more of the latter than the former), I picked myself up off the floor and moved on. Thankfully, there haven’t been many negative comments since, but the lesson has stood in good stead.

I realise that people cannot be disappointed with my writing, unless they have actually been drawn into the world of the book. So to that extent, I try and reassure myself that I have been able to engage my readers, even the critical ones. Beyond that, I ask myself if I could have done things differently. And once I answer that question—either way—I have made my peace with that particular input. I don’t believe in writing to suit a particular audience, but it would be irresponsible of me to not ask myself if I have done the best I could, for and with a story.

It’s become imperative these days to be a visible author. There is this compulsion to pin a face to the name of the author, at the very least. There are events, book launches, press releases, etc. to attend to promote your book. Have you felt that sort of pressure?

L.O.L. (can I say that in an interview?), yes! I can’t pretend that I did not enjoy the attention, initially; but it’s not in my personality to sustain that kind of activity for long. At some point, I begin wanting to be left alone with the next book. Don’t get me wrong, I love interacting with readers. I’ve sometimes gone on for hours exchanging tweets or Facebook messages with readers, but I count that as friendly conversation.

Visibility—I do fear it will change me a person, and I’m not ready for that at all. I’m not as mature or as detached as I ought to be, and it’s very tempting sometimes, to begin taking myself seriously.

What has the initial reaction been like? What’s been your most treasured feedback yet?

I think all the formal reviews have been positive. As someone who loves the craft of writing, positive mentions of style and language do mean a lot to me, as do acknowledgements of the research involved, and of the logical consistency of the plot.

But the really precious inputs come from the readers, firstly with the fact that they take the trouble to write in and say they’ve enjoyed the book, and then, of course, the personal glimpses they share: one person even admitted to having dreams about the characters, while another tweeted to say I was the first contemporary writer his father was reading in 10 years, and that his mother had stepped out to buy a copy for herself since the family copy of the book was in such demand!

One of the nicest things about being a writer—one of the things that I did not expect at all—is that you don’t just have readers. You make friends.

———

Click here to purchase Govinda.