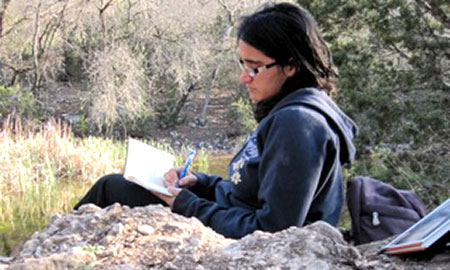

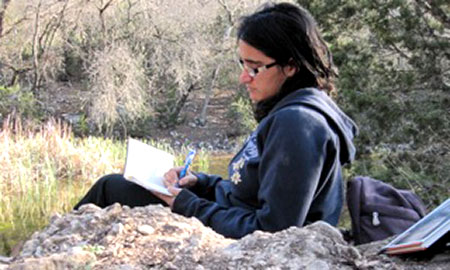

Aditi Rao is a poet, potter, and peace educator. Over the last eight years, she’s hopped between Argentina, Mexico, and the United States for her education and volunteer work. Her work has been long-listed for the Toto Funds the Arts Award for Creative Writing twice and won the Srinivas Rayaprol Poetry Prize in 2011. She’s the newest face in India’s tiny, but incendiary circle of young poets. Read on for excerpts from an exclusive interview—

Could you share an early writing memory with us?

We were assigned an essay, ‘If I were a peacock’ or something like that. My partner and I in school decided that we wanted to find interesting words to use. And I remember wanting to use a word other than ‘happy’ for when it’s raining and the thesaurus gave me the word ‘rhapsodic’. And I had no idea what ‘rhapsodic’ meant but there was just something about the sound of that word that just made me happy. And so many years later I remember the feeling of using that word because it sounded nice. The reason that strikes me, in retrospect, is that what sets poetry apart from other writing is that you’re listening for meaning, but you’re also listening for music.

Poet, potter, and peace educator.

That reminds me of what you said in one of your blog posts, about being surprised to win an award for poetry when you had published more prose than poetry. Do you write more prose?

I actually write more poetry. Publishing more prose has a little to do with that. Besides writing, my career path has been more in the N.G.O., youth development, peace education sector. It’s… easier to write for a cause in prose. I’ve started believing that it can be done in poetry but in terms of reaching an audience, it’s just easier to do it in prose. Most of the writing I’ve published has been in those kind of spaces rather than literary spaces. And even when it has been literary, it’s been with the Earth Charter and those kinds of things.

Over time, I’ve definitely started writing more poetry and I feel like I’m more honest and more fully myself in poetry. I’m not sure when this moment happened, but sometime in the last two years, as recently as that, that I realised that, because I really experience the world in images, in metaphor, and just that moment of realising that I could just say that, that I didn’t have to translate it into literal-speak. A lot of times I experienced the world physically, like I could feel an emotion in my body. And to just be able to say that instead of having to explain it through some other medium was an oddly liberating feeling. And I think you get away with that more in poetry than in prose. I think poetry draws more upon that sense where I may not get a poem literally, but I get the feeling that the author is trying to convey when she is saying that her hand is doing this or whatever.

So I think, in a lot of ways, it became the medium through which I expressed things, through which I felt I communicate in a different way. So, I don’t think I communicate better in poetry or prose, it’s just different kinds of communication. But I think the not having to publish has more to do with my never considering writing a career path. I do share my writing, I make little chapbooks of my writing and share them with friends. And it’s only now that I’m beginning to think about sending my work out into public spaces. But it feels like a very different kind of sharing.

What environment do you end up writing most productively in?

Time of day, definitely, morning. In terms of where, I think it has a lot to do with the mood I’m in and, of course, what I’m writing. If it’s something I’m doing research on then I like to be here [in my home office] because I have my books and my Internet [connection]. But I write, fairly regularly, in cafes and places like that. I can’t write in place like a library, it’s too quiet. But I do write well in a place like a café where nobody knows me, so they’re not talking to me, but their energy around me means there’s life around me. But I have created this home office space because I like the idea of writing at home and for extended periods of time. It depends a little also on what stage of writing [I’m at].

Actually the other interesting thing I think of in response to your question is that I discovered how different my writing is depending on where it’s written. In the summer of 2010, I had gone back to Mexico for six weeks to a small rural indigenous part of the country where I was working with a few friends and it was one of those times when you have absolutely no private space. Three or four of us shared a room, and I had no computer. And it was the first time in a long time when I just had to take a notebook and go out into the town public square or the market and my writing changed a lot over that summer. Because suddenly a lot of other people started entering it. Suddenly a lot of characters and their stories were emerging in my poetry and it wasn’t as closed somehow. Also, in terms of sounds, Spanish is my third language, and it’s their second language and they speak a local dialect which I don’t understand at all. So those unfamiliar sounds started to influence me. Since then I’ve made more of an effort to change the spaces from time to time. When I’m in the metro, I’ll just jot down interesting things that people say. I won’t write a poem then and there but they often become the start of something I end up writing.

You’re fluent at Spanish. Since you have two languages at hand, do you end up thinking and writing in both? Is it a mishmash?

Yes. And Hindi, of course. My base language is English but there are phrases from Hindi and Spanish that you can’t translate into English. Maybe you can, but… for instance something like adrak, in something that I was writing recently—I could say tea with ginger but it’s something that doesn’t feel right to me. Because saying chai with adrak is something completely different for me. In which case, I will say chai with adrak. This is something that used to be interesting while I was doing my Master’s because I was the only international and non-white student in my year. So all of them would stumble upon those words and ask ‘Why can’t you just say ginger if you mean ginger?’ and to someone who doesn’t speak more than one language it’s really hard to explain that ‘ginger’ and ‘adrak‘ feel completely different. So other languages do enter my work, I write my diary in a mix of languages for the same reason. While in the long run I would really like to write in different languages, that’s not where I am yet.

Is that a way of ensuring that you write your diary more regularly?

(Laughs) No, I don’t write my diary regularly. I wish I did. But I’ve written a diary since I was 12 and that’s just a way of not losing my mind. Sometimes it’s about how I record something really important that happened or something someone said or did. I also collect a lot of random things that remind me of particular places or people, some of which I stick into my diary. So in that sense I do hoard memories. But the real reason I write a diary is that I don’t know how else to clear my head. Lately I think why I don’t write as regularly is that I end up writing long emails to people. And a lot of that is because I’ve moved around so much in the last eight years; a lot of my closest friends are scattered all over the world. And so a lot of the processing and thinking that I would do in my diary now I do over emails.

Aditi Rao won the Srinivas Rayaprol Poetry Prize in 2011.

You’re also into pottery. Is there a different kind of fulfilment that you get from that than from writing?

Yes, there is. I think I got into pottery initially with no purpose in particular. My college had a mandatory arts class and I liked the idea of doing a pottery class, and then I did another. And while I was in New York doing my Master’s, I was doing a regular poetry class. My class was a few blocks away from the public library. So I would go to class and I would work there for a few hours and then I would walk over to the library and write. Pottery uses a different part of your mind and your attitude, because it’s completely non-verbal. It’s very skilled as an art form, you spend a lot of time just doing this (indicates with her hands the turning of clay). But you have to do that with a lot of focus, if your pressure is too much or too little, you could ruin your pot. And there’s something about having to be that still that creates this interesting mood from which to write. And I did find that I used to write very productively after pottery. And I think the reverse is also true. I think sometimes as a writer, you can get so caught up in the world of thoughts and ideas that there’s something about having to focus completely on something that has no words. You can’t really think about words when you’re doing pottery. They complement each other nicely.

That’s one part of the explanation. The other part is that since I was a kid I’ve always just really liked doing things with my hands. I’ve always been really big on making gifts for friends. I don’t like buying gifts and so almost all of my poetry from the last two years belongs to one or the other friend. And it would be a challenge I would give myself that for a particular birthday I’m going to make a mug that reminds me of a certain person.

In the narrow world of Indian Writing in English, what did winning the Rayaprol do for your writing?

I don’t know if it did anything to my writing. I don’t think an award or recognition should ever make a fundamental difference to one’s writing; that would be falling into the trap that I’ve been resisting by not publishing before I was ready to. My writing has to be honest to me and to my reader, and awards aren’t part of that equation. That said, winning the Rayaprol has definitely made a difference in terms of giving me exposure. Especially since it was awarded at the Hyderabad Literary Festival, where there were so many wonderful writers present, it gave me a chance to interact with and understand so much more about the whole world of contemporary Indian writing in English. I discovered poets whose work I had never read, and I got a chance to interact with them as a poet. Those conversations and friendships are perhaps the most important thing I got with the Rayaprol.

There was, of course, also the wonderful experience of having a huge audience for my reading at the festival. Being able to share my poetry with so many people who care about poetry back here in India, and then having so many of them come up to me later to share a thought or an experience or a memory sparked by that poem, was really special. Srilata (who was on my jury) and I also got a chance to read along with Adil Jussawalla for the students at the University of Hyderabad, and it was truly wonderful to share that platform. I had a poem called November in New York, Srilata read one about December in New York, and Adil took that forward with one about December in the U.K., and all of those spoke to similar themes of identity and foreignness. I think that was the most exciting part—discovering these other writers and feeling how our work was becoming part of a conversation. I think the main thing about the Rayaprol that I’m really grateful for is that introduction into a larger literary community and the sense of camaraderie I felt with so many other writers at the festival. It feels good to be able to claim and inhabit those spaces now that I’m back in India after so much time away. It’s like coming home… to a home I didn’t know existed.