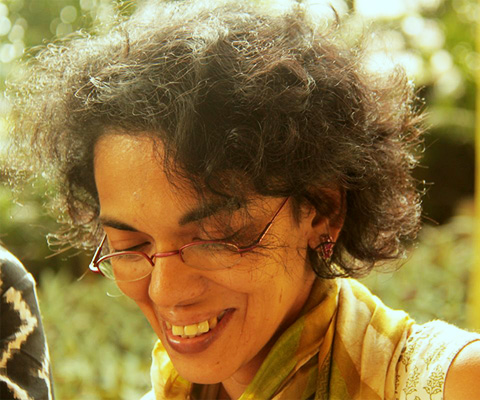

Karthika Nair is a dance producer and a poet. She translates words into dance performances, and reconstructs dance in her poems, bringing together these two universes to make us see them in a way that we’d previously not imagined. She co-scripted choreographer Akram Khan’s 2012 Laurence Olivier Award-winning dance production DESH, and Bearings, her first book of poems, was published in 2009 by HarperCollins India.

We spoke to Karthika in an exclusive interview about her poetry, scripting dances, and escaping labels. Read on for excerpts—

“Like poetry, dance happened to me.”

How did you first realise that you wanted to work in dance?

I didn’t, actually—like poetry, dance happened to me. Ironically, I landed my first job in contemporary dance because I knew nothing about the field. I had spent the first years after my D.E.S.S. in art management, working in traditional music and multidisciplinary art. Then a production manager’s position opened at the Centre national de la danse. They needed my financial and organisational skills but didn’t particularly want someone with any artistic awareness of dance. But movement art spoke to me with an immediacy that nothing else had, and I made it a point to watch as much as possible, all kinds of dance from experimental to traditional to hip-hop. I read, attended symposiums, and tried to grasp as much of its history and evolution as I could without an academic—or performative—background.

I left two years later to head the programming and production department of the Cité nationale de l’histoire de l’immigration, a new national museum in Paris. We got to invite some of the artists whose works I admired most, ones whose ghosts—or hair shirts—were most in sync with, or questioned, the concerns of the museum: the shifting nature of identity, migration, the body as a vector of memory, the permeability of borders. One of the commissioned choreographers was Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui: we enjoyed working together so much, especially writing together—Actes-Sud published a book on the piece which we co-wrote with the visual artists of the project—that when the art policy of the museum underwent some dramatic shifts (after the 2007 presidential and parliamentary elections), I left the museum to join Larbi at Het Toneelhuis, a regional theatre in Flanders. In 2009-10 we founded his company, Eastman. And since then, I’ve always been working directly alongside a choreographer as his/her producer instead of being part of an institution, where you may invite choreographers and present (or produce or commission) their work.

I was intrigued by your generous use of footnotes in the first section of Bearings. Very few writers supplement their work with context or references, but for me the notes actually lifted the words off the page and almost showed me a version of the dance. At the very least, they made me want to see the dance.

It is so heartening to hear that, and I am quite chuffed that they gave you an idea of the original piece! I wouldn’t have dared to, left to myself because I can be terribly verbose about things I love. But my publisher, V. K. Karthika at HarperCollins, really encouraged me to write those footnotes; she felt that the ekphrastic poems could be very elliptical if one didn’t have an idea about the specific performances they were referencing or ricocheting from. I loved writing those footnotes, finally, and instead of describing them, I just explained the context in which I’d encountered those works and what they meant to me. And Karthika (V. K.) was right, contemporary dance (or music) is such a small—and, in many ways, obscure—world; it needed to be mapped. It wasn’t like I was writing poetry on Da Vinci’s ‘Last Supper’ or the Taj Mahal, which everyone would immediately identify with or visualise.

Reading Bearings, I was struck by the different limitations of the two art forms (poetry and dance). In your experience, what does one do that the other can’t?

I think poetry and dance share this great strength: form mandates structure, and the bedrock for both dance and poetry for me is just that: structure, composition. The same misconceptions also exist with both: there is a belief that free verse can allow a total absence of structure, and similarly, that contemporary dance does not require composition (because it does not have a normative vocabulary like ballet, for instance). But that’s not true. What it’s given us—and I speak as a layperson—is greater freedom, but the freedom is to find our own individual structures, and those need to have their own ‘organicity’ for the piece to work, even if it doesn’t bear the label of a sonnet or a waltz. And isn’t it interesting that the French word for composition in dance is ‘écriture’ (writing)?

At least in my work, the choice of form depends on the source material. Take Tempus Fugit and the kissing tango I riff on for the villanelle by the same name (click here for the duet and here for the poem): the movement pattern just screamed for a villanelle—the coming together, the drawing apart, the final union, the lips that must not unlock. But we’ve written very different ‘stories’, Larbi and I: the kissing tango in his original dance piece has a distinct story for him, linked with the overall narrative, whereas in the poem I extrapolate it from the piece and transform it into a duet between the narrator and Time. But it is subjective. The day I wrote that poem I had seen the duet some seven times in one afternoon, during rehearsals, so the patterns leapt out at me, rather than the dance’s own narrative. And I thought, villanelle. Another poet could have seen something completely different, could have written a canzone, a ballade.

Dance’s greatest limitation, but also its incredible power, its grandeur, lies in its ephemeral nature. No two performances will ever be identical. Dance is calligraphy on water: the ripples vanish from sight even as they are being created. You could say that about music, I suppose, or all performance, to an extent. But technology has circumvented that to a great extent (and the music industry is flourishing proof of that). That isn’t true with dance. Merce Cunningham once said that we should see dance like we go visit a loved one whose time is near. I believe that: dance, each time, is like gulping a summer breeze while standing on the ledge of a cliff and waiting to be knocked down into the void.

Poetry, on the other hand, can be revisited: again and again and again. Bless it, that’s one of the things that makes life livable. The fact you can return to it, for clarity, for consolation, but also for the cruelty of truth and for strength. For remembrance. But poetry is not the body, directly. It is one step more, well, processed, perhaps. I think dance is imbibed—for want of a better word—in a slightly different way than poetry. There’s something very visceral that happens, from the body as instrument to the body as recipient, whereas poetry goes from brain to hands to paper/screen to hands that hold and eyes that read.

I think dance is imbibed in a slightly different way than poetry.

What kind of places do you find yourself writing in?

Hotel rooms. In the hospital, once I have the drip out of my arm—I never quite mastered the skill of writing with an I.V. line up my arm. Airports. The Thalys and Eurostar are great favourites. Home. Sometimes when I am desperate, the metro. I don’t get a lot of time to write, so all of it is precious.

Do you script dances often? Where do you usually find the stories for them?

DESH was my first and it was a staggering surprise when Akram Khan and his producer Farooq Chaudhry invited me to script the piece. Finding stories for DESH was not difficult—if anything, Akram and I devised and wrote far more than we used. Some of the stories were born out of the recent political history of Bangladesh, like the narrative of Noor Hossain, the martyr of the Dhaka Blocade of 1987. Others were inherited memories from Akram’s larger family, like the story of his uncle’s friend, who had the soles of his feet skinned by Pakistani soldiers during the 1971 war (which he turned into the story of his father for the piece). And one is an invented fable, which I wrote springboarding on two existing deities in the Sundarban, Bonbibi and Dakkhin Rai. Those are just most of the ones that made the final cut. I think we wrote about half-a-dozen more.

Every dance you script or produce must be a journey from inception to end. How does it feel when a production is done?

They are two different experiences. A dance piece one has produced doesn’t end with the premiere, that happens when the show stops touring—and then it’s a little like witnessing the death of an old, dear relative. Not because of the sorrow, even though there will be a bit of that, but from the sense of a passing on, of an approaching absence in the physical world. But a piece that you produce is not really yours—you are not the parent; you are the midwife, or the guardian. So there’s a distance you always maintain—for your own sanity, but also out of respect for the real parent. You accompany the piece, steer it away from puddles and sparks and make sure it is well-fed, warm, and, of course, you have long conversations with the real parent about its upbringing, its deportment, and so on. Ownership in this case would be misplaced.

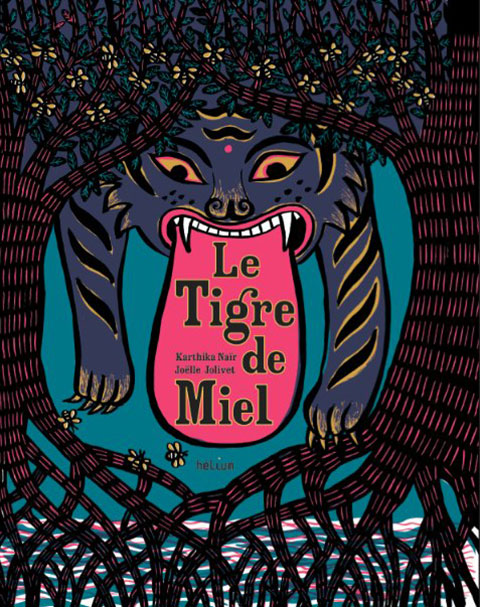

Le Tigre de Miel by Karthika Nair and Joëlle Jolivet.

How do you feel about your poems being set to music and staged? Does it ever feel like your work is moving away from the meaning and space in which you first conceptualised it?

The good thing about coming to scripting/writing for dance (or having one’s poems set to music) after years of working in the field as an enabler is that you are very clear that your poems and stories, your words, are no more and no less than raw material for each of the collaborators to transform into his or her medium. You are aware of the danger of retaining words just for their own sake. In fact, we had a guiding principle in DESH: the words were to remain words only when they could not become something else. So what you hear on stage as the spoken word is the pared down bits that are visible after all else has become, well, other matter.

Sometimes, when I see the piece again, there are sequences where I’d like even fewer words to be there. I’m a great advocate of silence, of the less-is-more policy. But that’s just my reaction—and it’s because I know those words by heart.

It is impossible for the audience, or most dance critics, to even fathom just how much writing has gone into this; they think all that’s happening is just the truth transposed. A dance piece isn’t like a play, so despite the credits clearly stating what our contribution is, most people think that “the poets wrote the text”—the spoken bits—whereas we actually devised and wrote the stories, only bits of which are still text, the rest is absorbed into multiple media. There are elaborate sequences that were scripted before they became animation and movement. One journalist asked me if I had written down the stories Akram told me—in other words, [if I had] been a glorified stenographer. That was really funny. But at least I don’t have to deal with the stuff Akram does—some journalists wrote about “his late father’s presence” in the piece. Mr. Khan, fortunately, is very much alive.

Would you identify yourself as a poet? Or is dance your everyday world, and poetry something that occurs in interludes?

That’s a very interesting question. It’s true that I tend to look over my shoulder when I am introduced as a poet, it doesn’t immediately occur to me that I am the person being referred to. But that isn’t really due to the omnipresence—or even intrusiveness—of dance in my world, it’s more a question of labels. I don’t always feel comfortable with labels—even wonderful ones, like poet, which, by the way, I still don’t always feel deserving of—after spending a good part of life battling the tag of the sick kid. It took escaping to another continent and rebuilding life from scratch to evade that partially. One never escapes labels. In France, for a long time I was labelled the Indian production manager (Indians in performing arts aren’t a dime a dozen, not in France). In Belgium, I am Larbi’s producer or—during the 15 months I was working with another choreographer—Larbi’s former manager. I am in Korea right now, and I keep getting introduced as the French poet (even if I don’t write in French); they are oblivious to the dance part of my life. Identity is a mutant and wriggly beast.

Akram said something startling the other day: he remarked that I look at dance as a poem (not surprising) and at poetry as choreography. That last bit was scarily perceptive, as it struck me that yes, words mean movement, and movement is what I constantly seek.

What’s next on the agenda for you?

Editions Hélium are publishing Le Tigre de Miel—the (translated) French edition of The Honey Hunter. The launch is this month. That’s the children’s book born from one of the stories I wrote for DESH, brilliantly illustrated by Joëlle Jolivet and translated into French by Dominique Vitalyos, whose work I’ve admired for long (her translation of Vaikom Muhammad Basheer’s Ntuppuppakkoranendarnnu—from Malayalam to French—is just pure delight). The original English edition is being published by Young Zubaan in India, and should be out early next year. Meanwhile, I am working on my next poetry collection, which revisits the Mahabharata through the eyes of 18 characters. There are plans to stage a part of that. So once I’ve finished the book, we begin work on the adaptation.