Nitoo Das is a teacher, poet, and photographer. She teaches English Literature at Indraprastha College for Women at the University of Delhi. Her poems have appeared in national and international publications such as Tehelka, Muse India, Pratilipi, Eclectica, Poetry International Web, and elsewhere. Her book of poems, Boki, was published in 2008 by Virtual Artists Collective.

An Assamese woman writing in English, Nitoo’s poems draw from the language and culture she grew up in. Her roots and her preoccupation with the natural world lend an earthy quality unique to her writing. One of the subjects that dominates her photography and to some extent her poetry is birds, and in both mediums she is able to capture them with immense clarity. She often reads out her poems, revealing greater rhythm and texture in her words than can be gauged from the page. Whether she is invoking the thumri to give Geeta Dutt a voice, or searching for the words to describe a wet cow, her poems resonate because of the depth with which she brings her canvases alive.

Nitoo recently spoke to us in an exclusive interview about writing and performing her poetry, teaching, and her love of birds. Read on for excerpts—

How long have you been writing poetry?

I remember my first poem. I was nine years old when I wrote it. It was a tragic poem about a “poor, church mouse”. A year earlier, at the age of eight, I had written an essay titled Autobiography of an Apple, which my teacher read out in grammar class. My first love, all through school and college, was prose: short stories and essays. In those days, I wrote very little poetry. At university, for a number of reasons, I stopped writing and did not write for almost a decade. In 2003, I was granted leave from work to complete my Ph.D. During this year, I got back to poetry with a vengeance.

The outsider. Photograph by Sanjay Gautam.

You are also a prolific photographer of birds. Numerous times in your poems, your love of birds and poetry intertwines. Could you tell us a little about how similar or dissimilar the two arts are?

This is a question that worries me. When I started photographing birds around four years ago, I thought that I would use birding and photography only as triggers for my poetry: something that would spark off ideas of seeing, framing, reconfiguring, etc. in my writing. However, birding soon became an obsession. I could no longer see it as merely a prompt for my writing. My poetry explores ideas of haziness, unknowability, subtraction, and blurring, whereas bird photography is about exactitude, knowing, and representation, almost in surplus of the bird’s presence. This difference haunts me, but “Without contraries is no progression”; therefore, I accept this fracture. Unlike poetry, birding demands physical mobility, the handling of heavy equipment, and study of taxonomy. It is also an entry into a predominantly male preserve. These issues further complicate my negotiations with two very varied ways of constructing reality. The only way in which they are slightly similar is in the space of post-processing. Photoshopping a photograph (cloning out a disturbing branch, saturating the colours, adding to the contrasts, blurring the background, etc.) and editing a poem can be seen as comparable methods of revising the original flash of the bird/poem.

Workspaces are fascinatingly diverse where writers are concerned. What kind of place do you prefer to write in or find yourself writing in?

I can write/make notes anywhere, but I prefer writing when I am at my desk; I write directly on the computer. Sometimes, very rarely, I go back to writing on paper with coloured pens. Writing on paper is a problem for me because I invariably end up making enormous and elaborate doodles. I like the freedom of writing onscreen. The possibilities that arise from constant deletion and the ease with which words, lines, stanzas can slither-skid around on the page make me happy. Also, I started understanding the rich potential of lineation and the visual impact of words on a page only after I started using the computer. I write only at night.

Can you describe to us the experience of performing poetry?

I like reading from my work. It gives me a high. I have some experience of theatre, which I try to bring to my readings. It is, I think, connected to my work as a teacher. In my opinion, a good teacher is also a good performer. I like poetry readings to be “theatrical”, even melodramatic on occasion. The audience, naturally, is a key component in the structuring of this performance.

There is a line in Sharanya Manivannan’s First Language that goes: ‘There’s a ghost of another language shadow-dancing under my words’. Does that come close to describing those of your poems that have their roots in the culture you grew up in?

Yes, that’s an apt way to describe some of my poems. Indeed, sometimes, they do not just shadow-dance, they violently colonise the poem I am writing. In Voiceless Velar Fricative, for example, Assamese words ambush the meaning of the poem.

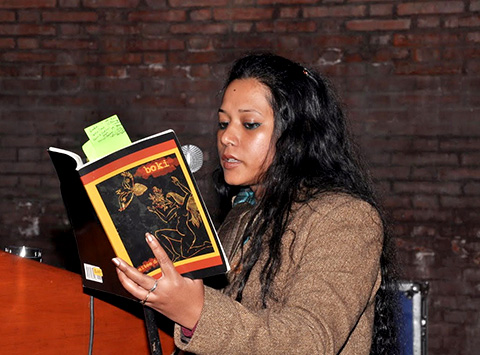

Nitoo Das reading from Boki. Photograph courtesy of Zubaan Books.

Some of your poems like Matsyagandha and Geeta Sings a Thumri rewrite female histories. Revisionist mythmaking is just one of the many practices common to your work and that of other women poets writing today. Why do you think this is so?

When I first started “voicing women” in my poetry, it was because I was trying to play with the form of the Dramatic Monologue. When I travelled back to writing in 2003, I had been teaching Robert Browning for three years or so. I used to teach Pandita Ramabai to students who had taken up Women’s Writing as an optional paper. Pandita Ramabai moved me enough to make me want to write about her. I wrote an epistolary series on her life, which was also an experiment with the Dramatic Monologue. Many of my early poems, written between 2002 and 2004—the Pandita Ramabai series, Swarn Noora, Doiboki, Harriet Hosmer to Louisa Ashburton, Gulabi Sapera, Naani to Ramher’s Bapu, Veerappan’s Daughter—were poems that dealt with experiments of voice/voicing. It was only later that I realised nearly all my voices were [those] of women who had not been able to voice themselves or had been silenced. The revisionist mythmaking that you refer to in your question is an idea that dawned on me after I had been writing such poetry for more than a year. Certainly, there was a vague germ at the back of my mind, but I started theorising about it post facto. Perhaps many women poets—my contemporaries—participate in this act of retrieval as part of their belief in the recovery of lost struggles. For a while, I did this myself. It is an intuitive act of faith. A desire to resurrect all those women who were abandoned by their societies. I have almost stopped writing poems with this schema because of a crisis in my conviction regarding issues of representation. What gives me the right to represent these women? Why should my version be a truer, a more privileged representation? Because I couldn’t find satisfactory answers to these questions, I have stopped writing poems like Matsyagandha and Geeta Sings a Thumri. I may return to such writing if I find suitable resolutions to the problems that trouble me.

I notice that you don’t write confessional poetry. Are there other ways in which you draw the personal into your poems?

The reason I don’t write (or seem not to write) “confessional poetry” is connected to my answer about the use of Dramatic Monologues. In a blog post I wrote in 2005, I had said the following: “1. I try not to write about myself. I write about people. Other people. 2. If in the tales of these other people, things, trees, something of my Self remains hidden, well then, fine. At least it’s hidden. 3. I look at the world around me and feel myself kindle with stories. So many stories to be told, why should I be trapped by mine? 4. An escape from my Self is not necessarily an escape from emotion.” The inside/outside divide is a false one, but can be used for specific purposes. In this sense, a poem about an ant or a bird would still be a confession about who I am. The Dramatic Monologue aided me in complicating problems of voice, ideological positioning, spatial/temporal location, embodiment itself. Now, when I think of the dependence on dissimilar voices to tell stories, the use of multiple conceptual personae, I cannot evade the idea that the self-styled “I” is a makeshift, provisional one, but an “I”, nonetheless. An “I” that looks like me in the mirror. Only inverted. In a twisted kind of way, this is one of the reasons why I no longer write poems like Matsyagandha.

You attended the Sangam House Residency last year. Could you tell us a little about what this time did for your writing?

It was a time of quiet. I documented the resident birds at Nrityagram. I met some wonderful people: dancers, writers, birdwatchers. (Meeting wonderful people is always good for one’s writing.) I organised the manuscript of my second book. I wrote some poems. A series I wrote on a woman called Padmamma is among the best I wrote there. Best is a relative term, but it means that I wrote about a person without feeling the need for disguises.

Do you think poetry can be taught?

Yes and no. I am definitely a teacher of poetry. There is no arguing with that. I am trained to dissect a poem—analyse all its images, count its syllables, examine the metaphors, break down its grammar into a bare skeleton—until it surrenders just about all its meanings. All one can do is teach someone to read a poem. I do not know if I have the answer to whether one can also teach someone to write a poem.

It’s been a few years since your book Boki came out. Is there another poetry collection in the pipeline?

I have a manuscript ready. It has been ready for more than a year now. Nobody has ever seen it in its entirety. Several poems from it have already been published. I am not sure if I want another book out yet. I have always had doubts about the place of mainstream publication of poetry. I oscillate between the need to publish and the need to disappear. I also suffer from a severe lack of ambition. I go through long periods when I do not think about writing poetry at all. Most poets will look askance at a statement like this. It is true for me, though. I do not feel an urgency to write down all the words and images that flit through me every day. I also think a physical book is overrated. Once in a while, magazines and journals request me for work and I send it to them. There is no guarantee that more people will read me if I publish a book. People do read me. On their phone screens, perhaps. And that’s enough.

This is a really good, insightful interview. Loved the questions as well as the answers. Thank you so much. Interviews so often make one feel as if one did not really learn or gain anything new after reading it which one did not already know before, but this one is really perceptive and satisfying, both by way of questions as well as answers. :-)

Where and why did my comment disappear?!