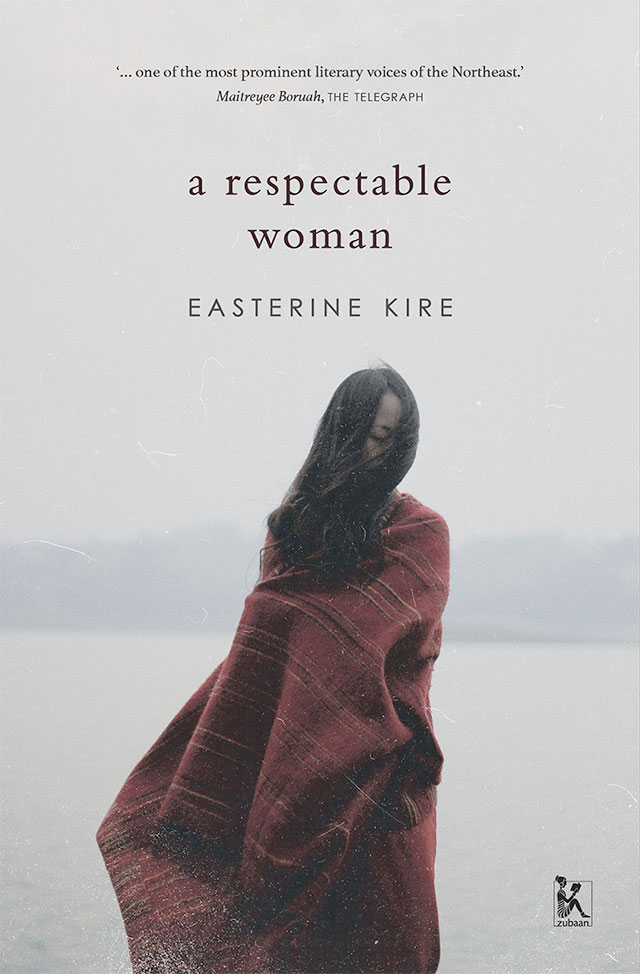

Easterine Kire’s new novel A Respectable Woman effortlessly weaves together generational family narratives with chapters of Nagaland’s tumultuous history, beginning with the Japanese invasion of Kohima during World War II.

Through the eyes of a mother and daughter, this unflinching feminist work explores the lives of characters fighting for a sense of normalcy during periods of upheaval and change. Kire, who is from Nagaland, uses intricate details and personal accounts to firmly ground the story in time and place, as she moves the reader through more than sixty years of Nagaland history.

Read on for an interview with the author—

Easterine Kire. Photograph by Per Wollen.

Your book is filled with meticulous detail. Can you tell us about how you approached the research process?

A Respectable Woman represents storytelling through the oral tradition. It begins from the post-war years in my hometown, Kohima, which was bombed out of existence during the Japanese invasion of 1944. The only books written about this were by British soldiers who had participated in the war, and the only insider nonfiction book on the war was the recently published The Road to Kohima by authors Charles Chasie and Harry Fecitt. I interviewed survivors and got their memories and used that to reconstruct what Kohima would have been like immediately after the war. I had earlier written a biographical novel, Mari, which was the first insider perspective on the war and the way it affected the Nagas. I had my notes from that earlier research as a starter. But you know, a book of this kind where very little written material is available, means you have to use what I call ‘living books of history.’ I interviewed many survivors and used their memories and recorded the history they carry with them.

What was it like speaking to members of your own family, and in particular your mother, about the war and its aftermath? Were there any elements of the conversation that surprised you?

I was fortunate to have made many notes when my mum was still alive. She was a teacher of history and gave me many valuable historical details. Plus, as a young girl of twelve, she had been a witness to the bombing of her home town and a few months later, she witnessed the major work of rebuilding. Not just that, my mum gave me so much information on the social structure, the school system, and the layout of the fledgling Kohima town in those days.

I also interviewed older cousins who were born after the war, and they were able to give me a very visual image of the town in the fifties. I greatly admired the spirit of the people. They had gone through so much and lost everything, but when peace came, everyone contributed to rebuilding the village and town. It was community spirit at its best, with the more fortunate ones helping those less fortunate than themselves.

Tell us about the title of the book. What made you want to engage, in this story’s context, with concepts of female respectability?

I wanted readers to question the title as it is such an arrogant, self-righteous concept. I mean, who should decide who is a respectable person and who is not? It’s a sad world where such notions exist, and right-thinking people should repudiate them.

What drives you to tell stories set in Nagaland? Tell us about your experience writing about a place underrepresented in popular literature.

I think being underrepresented should not be seen as a negative thing; rather, I would look at it as a big opportunity for our younger writers. It offers a space for Naga writers to decide in which direction they want to go.

We have an ancient oral, unwritten literature and a young written literature dating back to the 1970s when academic works by Nagas appeared in print. Before that, the writings that existed on Nagas were by western anthropologists and British political officers and American missionaries. I started writing historical novels on my people’s history because the insider’s voice was silent in all the historical narratives on us. Writing historical novels gave me the opportunity to give a socio-cultural presentation of my community. I always include the spiritual element as that is a big part of our reality as a people. I see the role of Naga writers as one of chronicling our history and our socio-cultural reality in the format of written literature.

Has Nagaland’s rich tradition of oral storytelling shaped your work? If so, in what ways?

Whichever story tradition a person comes from, it sits inside you and informs you and colours your imagination and your engagement with the world around you. For me, it is there at the core of me when I write stories of Nagaland.

In A Respectable Woman, characters occasionally encounter spirits of the deceased. Have you ever felt the presence of spirits?

We Nagas accept that the spiritual world is coexistent with the physical world. My grandfather saw a number of spirits in his lifetime. So have my cousin Marion Sircar and my brother David Kire. It is an exciting part of our reality.

I was five or six when I saw a child spirit, a little boy who invited me to play hide-and-seek. He was hiding under the dining table and calling to me. When I refused (because playtime was over), he disappeared, by degrees, not all at once. I remember feeling bad because he had looked so disappointed. Since that introduction to the world of spirits, I have had other spirit encounters as a grownup.

The spirit that the old woman encountered [in the book] often was a territorial spirit also sighted by the American missionary and by a young British soldier in 1944.

A fascinating aspect of the book is the characters’ fraught relationship with India. Are there elements of Nagaland’s history that you wish the rest of the country understood better?

A Respectable Woman is a book that touches on different phases of Naga history. The violent conflict between the new nation of India and the people of the Naga Hills in the fifties was a political conflict which the Nehru government tried to solve militarily. Terrible events happened at different points in history, under different leaders. Some people have problems differentiating between the historical and current political climate. When I write about historical events, I am documenting unwritten history. I am not trying to incite a movement, it’s very important to get that.

Has moving to Norway altered the ways you approach writing about Nagaland? Thinking about Nagaland?

Geographical distance provides different perspectives on a place, a culture, on socio-cultural and historical issues. I believe my writing is more objective because I have this geographical distance. It hasn’t altered the ways I think of Nagaland, but it has widened my perspectives to be more inclusive of the perspectives of others.

In addition to being a novelist, you are also a jazz poet. Tell us more about that. How did you first get interested in jazz poetry?

My father loved jazz and I inherited it from him. I am a member of a jazz poetry band in Norway, and I also perform with jazz musicians whenever the opportunity presents itself. In Delhi, we have a band called Jazztri, and we have done some gigs in the city. Quite fun.

Jazzing up poetry gives rhythm to music and also takes from it. It is an uplifting way to perform poetry and I love the liberating aspect that improvisation brings to performances.