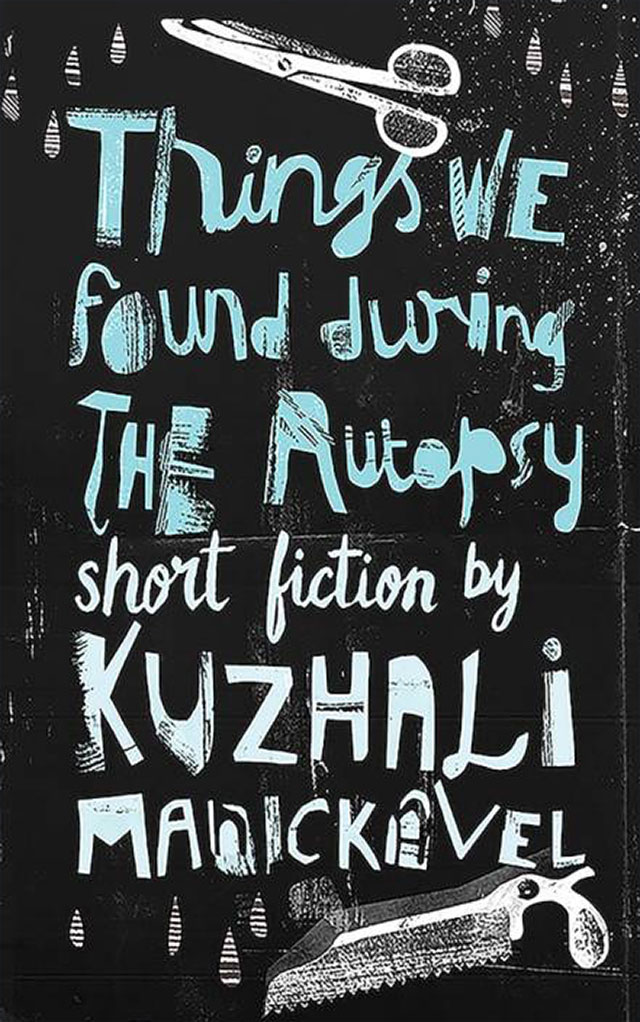

Things We Found During the Autopsy is the second short-fiction collection from Winnipeg-born, Bangalore resident Kuzhali Manickavel. Rather, perhaps ‘anti-fiction’ would be a better way to categorise this book.

George P Elliott describes this genre well: “Anti-fiction may include a story, but will fracture it. It may include characters, but they will be neither credible nor coherent. It forbids, ignores, or frustrates the reader’s usual sympathies and antipathies. Instead, it connects the reader with the narrator’s mind, which is in an abnormal state. At the mildest, it is in a state of perplexity about itself and its contents; at the extreme, it is in a state of despair, or of megalomaniacal suspiciousness (paranoia being anti-fiction’s madness of choice), or of nihilism.” Things We Found During the Autopsy brings together forty-five of Manickavel’s writings, from the micro-fiction-length ‘The Ash Eaters’ to the rare complete short story like ‘How Juniper Parsnip Saved Christmas Eve’.

The narratives follow thoughts, dreams, and memories into their remote, often-inaccessible dungeons—the ‘windmills of the mind’—culminating in unabashed explorations of taboo topics like rape fantasies or the stoning of children. The autopsy of the title is a reference to the picking apart of the human mind, sometimes leading to underground bird sanctuaries and at other times, to hilariously convoluted film plots. The lightly sketched-in characters who populate the book are all those who have fallen off the radar of conventional society and literally live in a world of their own. Some stories even congregate to make an internally consistent absurdist world, like the five set in a ‘Tropicool Icy-Land Urban Indian Slum’, with recurring bicycle-stealing Gentoo penguins and singing albino killer-whales. Dead seahorses falling from the sky are distinctly Murakamiesque. Some motifs that can be traced through the collection are casually cruel residents of women’s hostels, mistrustful, and broke friends and lovers, pretentious urban ideologues (Naxalites or ‘homeless’ hippies) and different manifestations of pornography.

Some of the darker preoccupations like those of suicide, depression, and spirit possession, are presented in a matter-of-fact and inevitable tone. Disturbing themes of everyday sexism and routine racism, are presented as strikingly banal. For instance, ‘Whore’ features a young girl’s encounter with sexual harassment and the unsettling ways she comes to terms with this trauma and internalises guilt and shame. In this and other stories, readers are refused any comfortable distance from the narrative, and instead find themselves directly implicated, by the use of the second-person pronoun. But nor is the narrator always innocent; in the opening story, she unflinchingly explains to us, “He did not think whores were into longevity and honourable things like that.”

At other places, entire stories are narrated in the future tense, in a wildly disconcerting sequence of events about to occur, before being wound up back into the uneventful present, like in ‘This Is Us and This Is Us Outside’. Especially lacerating are the several instances of scathing sarcasm—two of the methods towards attaining national greatness in ‘Discuss How India Will Become a Prosperous and Secure Nation in the Next Five Years’, are smiling benevolently at suicidal farmers, and saying ‘jai hind’in anticipation of the same reply. In similar faux-instructional manner parodying poverty tourism, is presented the foreigner’s guide, ‘How to Wear an Indian Village’.

This is not to imply that all such ‘experiments’ are successful; some are too self-indulgent, condensed and rushed; for instance, the listicle like titular story or ‘The Four Steps of Standard Plastination’, and ‘The Twins’. But what cannot be denied is the striking effect of sudden imageries and (temporarily) wistful longings. Sample for instance, “an angry tangle of love for his wife that sits on top of his stomach and gives him indigestion every night”. Or: “We sat by the telephone like we were waiting for someone to call us and tell us what was going to happen next”. The autobiographical undercurrent of the collection is nowhere more prominent than in the last piece, ‘Anarch’, where the angst-ridden experiences of growing up in a foreign country with conservative parents, resisting one’s home culture, coming to terms with suicidal friends, wondering about one’s sexuality, are traced through to the equally alienating experience of being sent to India, whose cultural codes become increasingly recognisable, if not relatable. N.R.I. experience here is not the usual fulfilled American dream of the melting pot, nor nostalgic yearning to go back to the homeland, but an amalgamation of frostbite, cheap shopping, maladjusted schoolmates, and racism.

A sense of unmoored rootlessness pervades the work, though not presented as tragic. Self-pity quickly gives way to self-deprecating humour at childish fantasies, with revealing sentences like, “You are sent to an all-girls college in India and this ruins any chances you have of becoming a single mother and living in an apartment with someone called Ryan or Darren.” The “one christmas story for children” (as whimsically listed out by the back cover as one of the constituent elements of this book), is ‘How Juniper Parsnip Saved Christmas Eve’, the most uncharacteristic entry in this collection. Adhering to conventional norms of a short story, and coming closest perhaps to the fairy tale genre, it nonetheless can be read as a cheekily subversive anti-Christmas story. Elsewhere, instead of Noah’s ark, we have Sully, the pimp who puts the bodies of his whores to literally make a ‘whore raft’.

The language suitably and disconcertingly, is a mixture of American slang, undifferentiated Tamil and Indianisms like ‘brothersister fellow’ and ‘fanty’. Epigraphs are purposefully misplaced, and create an uncanny sense of déjà vu. These experiments in form and content are refreshing at the least, in these times of political correctness. A cathartic experience is not what the book offers, but instead, the surprising recognition of oneself in the hints of characters, finding humour in the dreadful and darkness in cheerful, happy situations. Prepare to be thoroughly unsettled. Irreverent, rebellious, and blasphemous, the author’s schizophrenic voice bringing together the dark contours of her Canadian experience and her Indian one, shapes a distinctly compelling postmodern voice that cannot be ignored.

[Blaft Publications; ISBN 9789380636177]