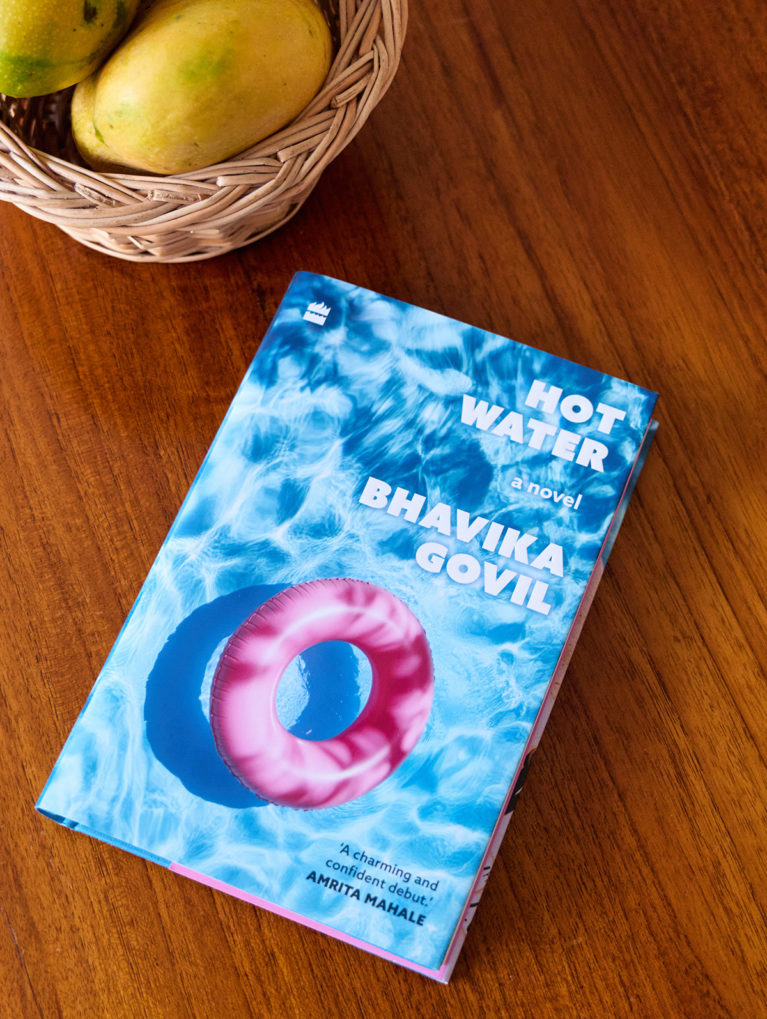

Bhavika Govil’s debut novel Hot Water takes place over the span of a long and hot summer, as nine-year-old Mira, fourteen-year-old Ashu, and Ma grapple with secrets that could imperil their entangled lives forever. Readers will view the world through the eyes of Mira, as she stows away secrets deep down in her stomach, where cake and other bad feelings reside; be privy to Ashu’s floundering as he makes sense of his yearnings; and witness Ma’s proclivity for bending and twisting her truths.

Hot Water is an intimate novel about what it means to love your family, even if it’s one you don’t quite understand. The author spoke with Helter Skelter in an exclusive interview about learning to step into the shoes of an imaginative nine-year-old, how water became the overarching theme of the novel, and the turning points in her writing journey that led to this book.

How did Hot Water start to take shape?

It was actually born out of a free writing session. The pandemic was just starting to appear in the news, and I was at a café in Edinburgh, where I was pursuing an M.Sc. in Creative Writing (from the University of Edinburgh) at the time. I was writing a scene where a little girl—who a few months later would be named Mira—has just returned home from school and entered the living room to find her mother and brother sitting on the couch, watching T.V. She senses that the atmosphere in the room isn’t the same as it was in the morning when she had left for school. She suspects that something has taken place in the room, but she doesn’t know what it may be. I ended the scene there. Soon after, the world shut down and I moved back home to India.

Until that point, I believed that a novel was at least 10 years down the line for me, that it was something I would have to chart out and plan far in advance. At the time, I had been writing short stories, some of which had been published. I intended to work on the short-story form further and hone my craft, but I kept finding myself drawn to that one scene. Something about it intrigued me. I was locked down at home with my family, and had to work on my dissertation, and I thought that while I could write more short stories—and it’s a form I admire so much—what’s the worst that could happen if I tried writing a novel? So I took a chance and leaned into Mira’s voice.

In 2021, a year into working on the novel, I submitted it on a whim to the Pontas & J J Bola Emerging Writers Prize. To my delight, I won the prize, following which I had an agent’s guidance. I spent a little over two years writing the first draft, and took another six months to polish it before submitting it to publishers. Again, in another serendipitous stroke, I found my publisher rather quickly; within two weeks of submission, I had an offer from HarperCollins India. While each stage of my journey has been lengthy, I’ve been fortunate to find people who have liked the novel and been open to collaborations.

Did you have a specific process or routine that you liked to follow while working on Hot Water?

This book has really travelled with me. I lived in lots of different cities around the world while I was working on Hot Water and somehow, each time I was uprooting myself from one place and moving on to the next, I also found myself with an important deadline to meet. While most of my time spent writing was peaceful, my most important writing days saw me dealing with major upheavals.

When it came to this novel, I liked to stick to a routine where I didn’t set very ambitious rules. I would get myself to write about 500 words a day. Once I got a sense of where the story was headed, writing would come a lot easier. And then, for the next two or three months, it would be easier to show up and just follow the lead that I had set for myself the previous day. Of course, there are always days that feel like pulling teeth, days when you’re struggling with the shape of the story. Those days lack structure. You can show up but you may not get very much done at all. Days like that involve oscillating between despair and desolation, and trying to write at least a little bit.

“While each stage of my journey has been lengthy, I’ve been fortunate to find people who have liked the novel and been open to collaborations.”

In Hot Water, you first introduce readers to Mira, an imaginative, eager-to-please nine-year-old. What was it like writing from the point of view of somebody so young?

Strangely, it was the easiest part of the novel for me. The novel was born from her— there was something so magnetic about her voice that drew me to her. It was liberating to write from her perspective because it felt like an exercise in being a child all over again, and getting to see the world again through her eyes. It helps, of course, to have read other child narrators in fiction. As a teenager, I loved the novel Room by Emma Donoghue. During the process of learning how to write Mira better, I read a quote by Elizabeth Baines that resonated with me. She said that the key to writing from a child’s point of view is simply never forgetting what it was like to be a child. Every time I entered Mira’s world, it was like shedding everything from over the many years I have gained since being her age. It was about seeing everything in a simple and more profound way. There was this de-familiarisation, questioning things that adults may assume as normal. Why is a word called what it is? Why is somebody not talking to me? Why is something called The Silent Treatment?

Writing from Mira’s point of view was also horrifying in a way, because you are occupying two spaces at the same time. You’re Mira and nine years old, but you’re still the writer who’s an adult, and you can see the things that she hasn’t understood and decoded yet. You’re innocent and you’re extremely aware, all at the same time. You want to protect the person you’re writing about, but you know that they must experience and go through things on their own.

“In a sense, I wanted the novel to be a manual for learning how to breathe, and by extension, learning how to live.”

The reader gets to experience the world through the eyes of all three characters: Mira, Ashu, and Ma. Was that always the direction or was it something that you arrived at later on?

It was always a story about the three of them, but whom the mic would pass to at what point in the novel, that was something that I figured out later. I wasn’t sure about the structure until I reached the end of Mira’s story. Ashu and Ma were always pivotal, even in the first scene; Mira’s world and imagination revolved around them, and getting to observe them. Both Ashu and Ma are as important to Hot Water as Mira is, but the decision to tell their stories was something that happened later. While they were always in my peripheral vision, I realised that I needed to let them turn towards me so that I could have the light shine on them.

While Mira and Ma are written in the first person, Ashu’s world is written using a third-person perspective. What influenced that decision?

I attempted to write Ashu in the first person, but he did not really reveal himself to me. Due to his introverted and gentle nature, it somehow felt out of character to write him in the first person. However, when written in the third person, the narrator hovers so close to Ashu that the reader has access to his inner world in a way that they’re able to see things that Ashu can’t quite see himself. Ashu is a boy of few words, with a vast and profound inner world, who lacks the skills to make sense of that deep interiority. Writing him in the third person helped me gain access to that world.

Among the three of them, Ashu was the most difficult to figure out. His world is so tainted with the love from his sister and the lack of it from other spaces, I ended up feeling deeply for him, and writing about him proved to be difficult. While the voices of Mira and Ma flowed easier, Ashu’s voice came through much like a trickle, and took its own time. He’s sort of a wallflower; it required an effort to seek him out and hear what he had to say, and yet, it was such a joy to put in that effort to bring him to life. He’s one of my favourite characters.

Were the section breaks in the novel—bearing swimming-related titles such as ‘Plunge’, ‘Surface’, and ‘Float’—always part of your plan for the novel?

The section breaks feel so natural now, but they weren’t always a part of the novel. They were always at the back of my mind, though. Someone I know told me that the novel seemed to have a swimming-floating-sinking structure, in the context of the three-act structure in fiction. Initially, the structure was such that one was introduced to Mira first, who represented the swimming bit, followed by Ashu, who, by virtue of occupying two spaces at once, resembled the act of floating, and Ma’s darkness mirrored that of sinking. The novel’s structure eventually shifted, but that comment remained with me.

From the outset, water (and the act of swimming) has been indelibly associated with the story. It’s a place that the characters keep returning to, and as they do, newer parts of them are revealed. Once I had the structure of the novel in place, I wondered how I could marry the text with the overarching theme of water. To me, it resembles, so closely, the theme of learning how to breathe amidst the claustrophobia and suffocation of being with your family, whom you love and at the same time, don’t understand. In a sense, I wanted the novel to be a manual for learning how to breathe, and by extension, learning how to live. I’m also quite happy with the design choice that the publishers made: white text offset against a dark background. It brings to mind the sensation of being engulfed in deep waters.

Even the cover, which at first glance looks like it’s perfect for taking along to the beach or to the pool, has both light and dark patches on it, suggesting ominous undercurrents. It contains both lightness and darkness, much like the novel does.

You’d already published several short stories before Hot Water. How did the experience of writing a novel compare?

Short stories are very rewarding in that they demand less from you in terms of time; there is a sense of instant gratification. When things go off course, it’s easier to fix them and have them return to where you want them to be. I also love short stories for the experience they offer, of inhabiting the lives of different characters and occupying their spaces in such a short span of time. The novel, on the other hand, is a much longer journey. With Hot Water, this journey has felt very intimate for me. I have spent so much time over the last few years thinking about Mira, Ashu, and Ma, and their lives leading up to the events of that summer, and what their futures might look like following the ending of Hot Water. They’re not just voices in my head. They’re real, and have flesh and blood and bone. It has felt very rewarding to hold on to their lives, even on days when writing about them was difficult.

You now lead writing workshops—how did that start? Do you see yourself continuing to offer more of them in the future?

Apart from writing, I love reading about writing and speaking about it. Since I have gained so much from attending writing classes, learning from the experiences of writers who spend far more time doing this than I do, and being in feedback circles, I want to pass that on to other writers. Writers often like to imagine we’re navigating the journey alone, working in isolation—but the truth is, no part of making art is ever entirely solitary. For instance, Hot Water would not have been possible without other people’s feedback, them being generous with their time, and even choosing to pick up a copy of the book now. Teaching entails being at a point where curiosity meets a love of craft, and that’s where I am right now. I’m currently enjoying conducting writing workshops, but in the future, I hope to take on different kinds of sessions, perhaps addressing voice and writing authentically.