Kutti Revathi is a prominent Tamil poet who has published nine books of poetry. Her second book of poems titled Mulaigal (Breasts) found itself in the middle of a raging controversy in Tamil Nadu for its portrayal of female sexuality and use of Tamil words like mulaigal and yoni (vagina).

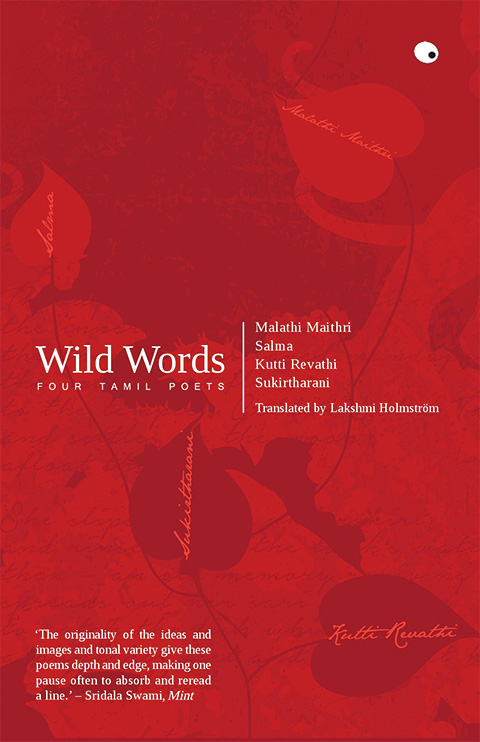

She received hate mail and death threats. Male poets expressed anger and criticism of her work. In spite of the public outrage, Revathi’s poems were recognised for their carefully crafted images and their sensitivity to body politics, and were widely read and translated. In 2015, HarperCollins published Wild Words: Four Tamil Poets, featuring translations by Lakshmi Holmstrom of the work of Malathi Maithri, Salma, Kutti Revathi, and Sukirtharani, all of whom came to prominence in the early 2000s and received censure for their depiction of female sexuality. She is also the editor of Panikkudam, a quarterly for women’s writing and also the first Tamil feminist magazine, and was featured in an award-winning short film called SheWrite about Tamil women poets. Some of her poems in the original Tamil and in translation can be read here.

In this interview, Kutti Revathi talks to us about being gifted books by her father despite her mother’s protests, the dark period in her life during the controversy surrounding her work, and coming out of that experience as a writer with a renewed sense of commitment to her writing and her feminism. Read on for excerpts—

Kutti Revathi’s poems have been recognised for their carefully crafted images and their sensitivity to body politics.

Can you share an early writing memory with us?

I started writing from my school days. My father had shared with me that he had struggled to get an education. He had an elder brother and a younger brother. They had lost their mother at a young age. Somehow their father only had an interest in providing education to his eldest son. That affected my father hugely. Whenever, my father tried to go to school, he was dragged through the roads back to the places he was supposed to be slogging in as a labourer. My father’s experiences were tearful and still lingering in my head even after his demise. He inspired me through the poems he was able to memorise through his limited exposure to literary knowledge, like Avvaiyar, Thirukural and Sangam poems. In those days, people had the habit of reciting poems by heart. My father knew very few poems and he taught me everything he knew. He introduced me to a number of books and was keen on cultivating the reading habit indirectly. Whenever my father travelled to towns and other places outside our native place, he used to buy a lot of old literary books for cheaper prices. My mother used to yell at us for this, always saying, ‘You spoil a girl by giving her more books.’ I still remember; all women of my age share this kind of strange memory in common, of reading story books by hiding them inside their school books. With the support of my father, I read all those books openly. I started participating in inter-school essays, poetry and story competitions, and my father was proud of my growth as a writer. I used to write diaries too. That way, ‘writing’ took over me in a more profound way and in an impactful measure.

What prompted you to write poetry? Were there role models in Tamil literature that influenced you?

After school, I studied Indigenous Tamil Medical System, Bachelor of Siddha Medicine and Surgery, which is a professional course in Tamil Nadu that spans five-and-a-half years. To study that, you need to have Tamil as a basic language—the complete syllabus is in Tamil and the lessons are in the form of poetic verses. It enlightened me greatly language-wise and literature-wise, and prompted me to engage in poetry continuously. That was a time, at the end of the ’90s, when an intense legacy of Tamil writers were there to inspire [one], though I am critically having different opinions on them now.

Your images are so perfectly sculpted. Do you write your poems in one sitting, or do you edit them over time?

I am glad, if you perceive [it to be] so. I am a person who thinks visually. That is because I was rooted in a film society—Kanchanai Film Society—that fed me with cinematic knowledge and the evolution of cinema. It helped me to blend language and visual insights. Most of the time, I do write in one sitting. But before writing it down on paper, it takes its intense time processing in [my] imagination. I have a habit of deleting poems if I am not satisfied with the language, composition, content, or with their intensity, even in a small way. And whenever I finish a poetry collection, I send the collection to a good poet for edits. I will opt for the final editing, though I intend to appreciate their comments. But primarily, the editing is done in my head when the poetry strikes me the very first time. I have developed the habit of catching it by the tail with all my consciousness. That is a good and simple way to write your own poems with all their original texture, isn’t it?

How has the controversy surrounding your books affected you as a writer?

Poonaiyai Pola Alaiyum Velichcham (Light Prowls Like a Cat) was my first collection of poems. It received good reviews from all quarters and I was seen as a hopeful young woman poet. Then happened the publishing of my second poetry collection titled Mulaigal (Breasts). The scenario changed drastically. In a commercial film, Sandaikozhi, my name was used specifically for abusing a character in the movie. Many women writers protested against the film, the scriptwriter (who is a novelist himself) and the director, asking them to remove the dialogue. For that, I was getting hundreds of posts with obnoxious comments. I see the hatred still prevailing among the community, even among women writers who cannot digest a poet naming her book Mulaigal. As a medical person by profession, I could see the sociofeminist politics of breasts as a woman. Then I realised the importance of me continuing my writing as a poet exploring body politics and the role of women’s sexuality in writing. Though for a short period, I was very depressed and was threatened non-stop by the media, I was able to come back to writing because by then I understood that society has sent back a number of emerging women writers to their homes like this before. The controversy effected me hugely in a positive way and made me stronger, I believe, when I look back on it today. One good thing that happened for Tamil women poetry is Anjali Monteiro and Jeyasankar made a documentary on the women poets who wrote on body politics, SheWrite, that opened national literary doors and emphasised the necessity to discuss the issue. Next, Arshia Sattar, of Sangam House, made the effort to bring out a translation of these poetry that made it an international discussion.

You received a grant from Sahitya Akademi to travel and meet leading littérateurs from India. Can you tell us a little about that experience?

I decided to meet the powerful writer Mahasweta Devi at her place and to stay with her for few days. Though I informed and fixed a date with her, she had completely forgotten when I reached her. She was very disturbed when I entered her house, as her schedule is fully piled up with a number of appointments. Despite that, she decided to take me in and kept me by her side the whole day. She shared a number of things with me as she was working along. One of the things that I can never forget from her insights are that our writing should always reflect the oppressed people of the society. That will make you a powerful writer. And another thing is that women should not wear bangles, earrings, and anklets, as they are the symbols of manacles.

When you see your poems in translation, how do you feel?

You know, it was difficult to find a space to express my views and publish my poems after the controversy of Mulaigal in the media. I was totally negated from the literary scenario. But I felt a huge urge to put forth the poetic outcomes that I had explored after Mulaigal. So I initiated a publication and a feminist literary magazine called, Panikkudam (Amniotic Sac). It was like a platform for renowned women writers who were addressing body politics, predominantly. For so many years, after being neglected and eliminated from the mainstream, the translation of my poems was quite a change of scenario, not only for me, but for every writer who was affected by the controversy. To see the translation of my poems was a thrilling experience, and it took us, our poetic cry, to the other side of the world, [to] all the corners of the literary and feministic world. Lakshmi Holmstrom was generous enough to do the translation of our poems and I was proud to take it with me to international poetry festivals wherever I went. The translation opened the floors to the powerful poems of the poets who were continuing to write about body politics in spite of controversies. And now, after fifteen years of the struggle, the mainstream magazines don’t have any resistance, hesitation, or inhibition in publishing poetry by women. The scenario has changed only after the translation and only because of the translation. The power of the poems is visible.

They call you poet, feminist, activist. How do you identify?

I am only entirely happy when I am titled poet. In the Indian scenario, women cannot be brought under one single umbrella, as ‘women’, as we are discriminated by caste, religion, and other oppressive factors. The feminism that has been downloaded from western countries is not supportive enough to address the complexities and the intricacies of our issues, as every single woman has to come up with her own notion of feminism and rights. To overcome this huge difference, casteism and oppression of women of different social strata in our country has to be discussed elaborately, with much social concern and understanding. But mostly the intellectualism of Indian women is a collective one, from the urban class and upper caste, that thinks that caste is a privileged identity and they are not ready to see their vulnerability. The oppression and violence are not just because they are women but also because they carry a caste tag with them. These days being a poet itself is being an activist after the demise of Rohith Vemula and the emergence of the oppressed in this country that has followed. Being a poet is a very powerful thing in this nation, whether you write in regional languages or in English.

In another interview, you said: “The present social condition demands us women writers to be a lot of things at once. Earlier, writers had the privilege to be only writers…” Do you feel the pressure to be a certain kind of writer?

I long only to be a writer. But even to be only a writer, we need to carry a number of demanding roles. The pressure of vulnerability, oppression, sexism, and violence of women is growing, as her personality is an evolving one. So, to come out of these, freeing herself, she has to be a lot of things at once; has to handle herself. She has to realise what kind of systems the family and marriage are and has to accommodate her powerful womanhood in that patriarchal and Brahminical system of dynamics. She has to feed herself with all the knowledge and the wisdom of modern ages and has to be playing a role in the social domain so that she is not identifying herself as a single woman anymore but part of the women community of the nation. She has to be in terms and updating herself with the demands of contemporary feministic intentions and notions. She has to be thinking ultra-modern and of being an alpha woman. There are a number of demands. But the longing to be a writer, and at times to be an anonymous writer so that you can voice your opinion more frankly and uncensored, is my big dream. To be only a writer, that is what I wish for.

What are you working on at the moment?

I am going to direct a movie now. Everything is set up for the production and it will start sometime in May. It is a script by a renowned fiction writer, Dhamayanthi. She is a very sensitive screenplay writer. In this story, we have addressed a very contemporary issue which the society needs to heed urgently. As I said in the beginning of this interview, I have always wanted to interpret women and the caste issues of India through visual elements. Laura Mulvey, a feminist scholar, clearly addressed this in her times and in her writings. The female gaze can bring out liberation in this age of social media. We are inundated with images that have no sensitivity on the understanding of women, men, humanity, body. The oppressed women are the most vulnerable. I want to make a serious attempt regarding this in my movie profession.