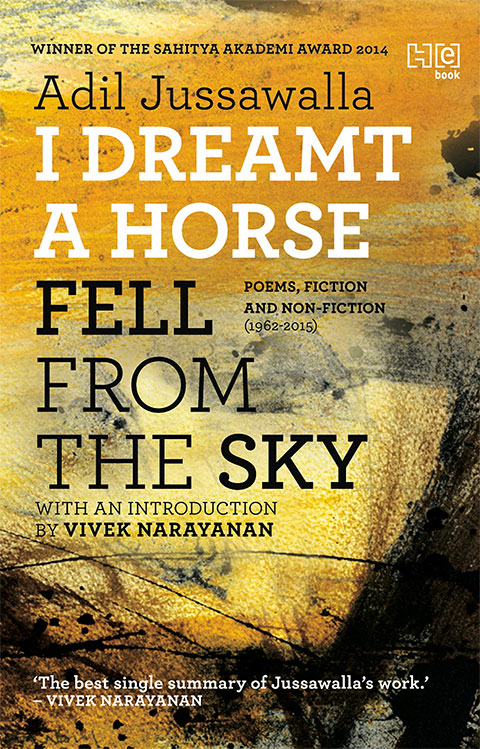

The eighteen new poems that comprise the first section of Adil Jussawalla’s recently published I Dreamt a Horse Fell From the Sky, which brings together a selection of his verse, fiction and essays, open “into each other/ like rooms that share a door”. That is how the narrator of the second poem, Shorelines, describes the looks exchanged by two women who give him shelter one stormy night. “We’re all castaways here,” a woman who gives him refuge on another shoreline says. The next poem, set in the bleak future, picks up this line; other poems, other themes, other images, creating a kaleidoscopic chain of echoes.

These new poems come rather close on the heels of Jussawalla’s previous collection, Trying to Say Goodbye (2012), while also building on two major themes from that work: ageing and memory. Certainly, we are glad that the goodbye, which itself was attempted after a long gap of thirty-six years (Jussawalla’s last volume of poems was published in 1976), never actually happened. The opening poem in the selection, The Deep, beckons us to slide down to a watery underworld where the “emptied mind” will have to confront both illumination and terror: “Well caught but bravely astir/ is how most of us try to live after all”, the poem tells us. And so we stir and shudder, “our bodies subject to [growing] bends and cramps”, until one day we lose the ability to “sail home as steady as herons” (Old Men on a Beach).

The sea figures prominently here, sweeping its way into poem after poem, calmly and ineluctably, limitless in The Sea at Den Haag and almost invisible at night in Shorelines, but beyond which lie other unseen and imagined worlds, other wonders. The sea also becomes the site of religious conversion for the narrator’s friend, Suleiman, in the mock-serious The Road to Versova. Saul becomes Suleiman, and Damascus, Versova, in this twenty-first century and local rendering of the famous biblical episode. The Kolis of the fishing village come giggling to the aid of the thunderstruck man, while in the clipped tones of the scriptures, we are told: “The air stank and fish dried”. Was Suleiman, too, out on some sinister mission? Was he blinded? Did the Kolis see or hear what Suleiman did? We are not told. But, on some roads, “the thunder of the question doesn’t stop”.

Matters of faith are again taken up in the last two poems, which deal with snake worship and canonised specks of dust. In the first, the “flat pan” (Cobra Bhakti) of the narrator’s brain shrinks the innumerable names of the snake god to the single and humble, but variously intoned, pronoun “You”, while in St. Mote, we gain inspiration from a particle that drifts into “our lives on a chance ray of light”.

Two poems talk about gardens. The papery narrator of Turning Seventy sits calmly in the face of imminent incineration, because he has taken up the Persian poet Sa’adi’s invocation: “Breathe easy in the garden and be glad”. In the second, The Garden’s Earth Yawns and also breathes and pants like its resident dog, although this excitement is restricted to certain days.

Two other poems concern kites and kite fights. Soaring no more, watched by “people [who] have gathered/ as though wanting to see if someone will let it in” (Kite), a cut and plummeting kite becomes an object of idle curiosity, like a victim of an accident or a crime, “till a boy shouts and shows what it means to him”. Defeated kites also recall The Deep, for they may be found “… balancing/ like nervous divers on the rims of wells” (Reply to a Postcard from Overseas).

Wandering from poem to poem, much like castaways ourselves, we encounter visions of haunting clarity: “acres of bloodless coral” (The Deep), “dud robots, pouches of spoiled powders” (Castaway City), “oils, turds, the slops of ritual” (Cuffe Parade) and a fish eye “fixed on you in wonder, as you scrape out what’s left in its head” (Evolution, After a Fashion – 1). From a Manual of Maritime Signals consists of a series of eerily calm and slowly fading messages beamed to and from a vessel in peril. (It makes me think of Gary Lockwood’s astronaut in 2001: A Space Odyssey, spinning mutely and helplessly through the vastness of space.) And in Just in Case, we find what could become a veritable catchphrase for our troubled age: “Why? Why? Why?/ It’s a national puzzle”. (That’s two whys less, you will notice, than Sakichi Toyoda’s celebrated problem-solving method. Will that get us any sooner, though, to the source of the burning issue?)

But to return to and close with that potent and recurring symbol, the sea: the narrator of Cuffe Parade, wakeful and watching the “flat eye” of cautionary but unconsoling light, muses:

But why be depressed?

So this curse be lightly lifted—

or to make us believe it will be—

so our days get no heavier,

it’ll soon be sunrise.

Strain your ears a little, and you might hear the gentle rustle of a kite landing, or the garden’s earth or Suleiman sigh, “Amen.”