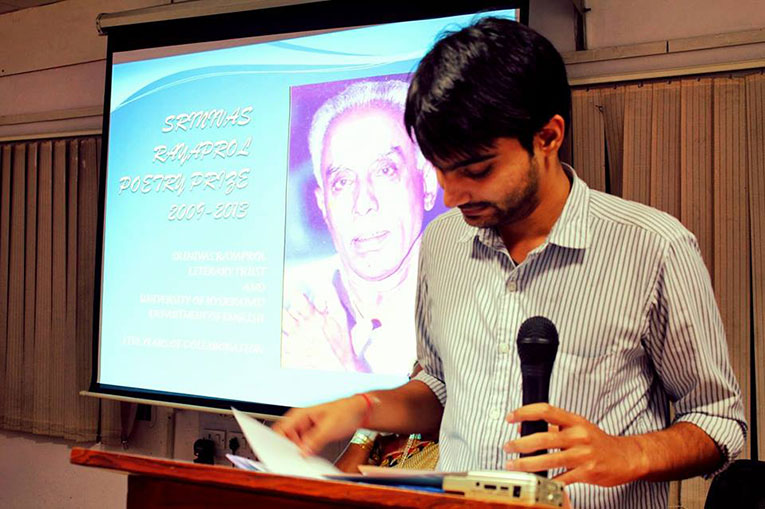

Mihir Vatsa is the recipient of the Srinivas Rayaprol Poetry Prize for 2013. He grew up in Hazaribagh, Jharkhand, and currently lives in New Delhi where he is pursuing a postgraduate degree in English. His poems have appeared in Eclectica Magazine, The Four Quarters Magazine, UCity Review and elsewhere. Since its inception in 2011, Mihir has been the poetry editor at Vayavya, and he also curates Tales of Hazaribagh, a website dedicated to documenting his home-town.

We spoke to the young writer in an exclusive interview about poetry and growing up in Jharkhand. Read on for excerpts—

Mihir Vatsa speaking at the Srinivas Rayaprol Poetry Prize event in Hyderabad. Photograph by Shruti Singhal.

If you had to describe the town where you grew up in a few sentences, what would you say?

I grew up in Hazaribagh, a small town in the lesser-known state of Jharkhand. It’s a lovely place in the North Chhotanagpur plateau, heavily forested in certain areas, surrounded by a few hills, with excellent weather. If you are courageous enough to venture into the woods then there are chances that you may discover a waterfall or two on your own. Besides being a cool, quiet place for someone who enjoys a rustic lifestyle, Hazaribagh also offers a great deal of insight into the intermingling of the tribal culture of Jharkhand with the “mainstream” one. There are a few market complexes as well as villages practising the indigenous art form of Sohrai on the sun-baked mud walls. There are prehistoric rock-art sites which are believed to date back as far as to 9500 B.C., megalithic complexes displaying an excellent understanding of astronomy, and ruins of the Ramgarh royal kingdom of the Raj period.

In a way, Hazaribagh offers a chronology, starting from 9500 B.C. to the present, and it’s something which fascinates me. The Hazaribagh town itself can be circled in a radius of about 5 k.m., so you can always find one or two familiar faces on every street. Then there are some shops whose identities have become synonymous with the goods they sell. For example, there’s a shop called Khandelwal, where everyone from Hazaribagh buys books—textbooks, novels, self-help, everything. Even if the store-boys don’t know what ‘self-help’ means, the store will have a selection for you anyway. It’s cute. I remember placing an advance order for Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows at the store so that I could get it on the day of its release.

Tell us about a poem you particularly favour, something that’s close to you.

What Work Is by Philip Levine. It’s a poem I can read all day and yet feel that urge to read it once again. It’s a poem I force my friends to read because it’s so bluntly honest and true. Lines like, “You know what work is—if you’re / old enough to read this you know what / work is, although you may not do it” ring a bell. And how wonderfully he creates that particular scene where this “you” person mistakes a man for his brother because of a few similar physical attributes only to realise later that “of course, it’s someone else’s brother”. There’s no forced introduction of poetic devices in this poem, the language is simple and effective. No useless diversions.

“The more I read, the more I interacted, the more perspectives I got.”

What kind of environment do you find yourself writing most productively in?

Nights, certainly. Also, I need to have my laptop with me, otherwise I can’t write a thing. Maybe it’s because I began writing on Microsoft Word itself. 12-point, Baskerville Old Face. I also like Garamond. Sometimes I write immediately after reading a poem on the Internet. Some poems are like that. They have certain words or phrases that trigger an idea. Once I read a poem with such an elusive language that I ended up writing a poem about a dream with Derrida in it.

Who would you say are your main poetic influences?

When I started writing on a regular basis, around 2010, I made a major mistake which every excited young writer makes. I did not read enough. Yes, I read what was in my course, like a good student. I read the poems we had by Browning, and I was stunned by the poems of Jayanta Mahapatra. I liked Donne because he didn’t focus much on preserving chastity and other virtues. His narration was bold and refreshing. I couldn’t believe that someone in the 16th century could be so cool! So, my early influences were the poets I came to know from the course itself. Somehow the idea of poetry existing outside of a literature course didn’t occur to me. It was only in late 2011 that I started looking for poetry in our own time.

I was introduced to a few poems by Sharon Olds and I began to understand the dynamics of relationships, especially within a family, through her work. Family is a theme I am currently interested in. Amitav Ghosh’s The Shadow Lines taught me that time need not always be a rope starting at one point and ending in another. From there, I started splitting time into segments to look for stories in them. This process helped me understand many things, including a few incidents from my own life, which I wouldn’t have understood otherwise. I began interacting with other writers active in the present—Nabina Das, Sumana Roy, Aruni Kashyap, among many others. I wrote emails to writers whose works I found on the Internet and loved. The more I read, the more I interacted, the more perspectives I got. So it’s tough to list my influences, for there are many.

Are you primarily a poet or do you also write prose?

I feel more confident with poetry right now, not so much with prose. Even when I do write prose, I prefer non-fiction. Short essays and memoirs. I have written a few short stories, but am also aware that I need more practice and discipline to turn them into stories that “work”. Maybe someday I’ll write a novel. I don’t know. But right now, it’s only poetry.

What does being a poetry editor bring to your life? Does it bring anything to your poetry?

First of all, it brings me lots and lots of poems for free! Yes, it’s a perk. But it’s also an inferior perk. Some poems are good and some not so good. You don’t have an option to savour only the cream. It takes time as well—right now, I spend one hour every day with the submissions. Sometimes I get lucky with an empty inbox, and sometimes, especially after an issue goes live, submissions come rushing in. Sometimes, a brilliant submission comes my way and blows my mind, and the poet in me aspires to reach to that level. I will be lying if I say it doesn’t happen. It does. It’s easier to identify a good poem than to write one. When a senior poet with an impressive cover letter sends their submission, yes, I do feel a bit intimidated. But I also know that I have in me what it takes to be an editor, thanks to my peers who have very rigorously taught me the technical aspects of poetry. Then there are also those dreadful moments when you must say no to a submission made by a friend. It’s a learning experience, which I enjoy, given one or two cons that come with the job.

“I have decided not to think too much about what my future is going to hold.”

What’s next for you? What are you hoping for?

I returned from Hyderabad at midnight on October 26. The [Srinivas Rayaprol Poetry Prize] event, reading, and the response I received were all wonderful. However, upon returning, Delhi grounded me again. There is a term paper due soon and semester exams begin on November 20. I’m worried about both. But honestly, I have little idea about my future. Would I like to do an M.F.A.? Yes, I would. When? I don’t know. Would I like to do an M.Phil. or a Ph.D.? Yes, I would. However, there are chances that I may end up doing neither of the two. I think of these questions sometimes and get anxious. So I have decided not to think too much about what my future is going to hold. Some would call it carelessness, but that’s fine by me. Like I said earlier, I like breaking time and enjoying the segments for what they are. This is also one such segment, this affirmation which has come with the award that I am a poet, and I hope to enjoy it as much as I can, only to return to it later with a fresh perspective. I would like to do many things. I’d like to do things for my hometown to which I owe this award. I’d like to make Vayavya a paying venture. I don’t know when it would be possible, but I do know that though I may not have much experience in my life so far, though I may be a student still, learning the ways of poetry and world, I have time on my hands. I guess that’s one advantage of being twenty-two.

You said you owed the Srinivas Rayaprol Poetry Prize to Hazaribagh. Could you elaborate?

It’s complicated. For me, Hazaribagh is a town which breathes, though slowly, and sleeps a lot. It is alive, like a lazy person, and has given me memories I often go back to in my poems. I enjoy travelling, and consider myself a place enthusiast. I identify a place with a particular sense. For example, I recall the government quarters I grew up in whenever I smell a fresh coat of quicklime on the walls. In doing so, I build a relationship which I want others to understand and appreciate. If not appreciate, then thrash, but do something. So I write about it in my poems. When I say that I am a poet from Jharkhand, it’s a conscious decision to present myself that way. I’m not ashamed of the idea that I come from an under-developed state. I was born there, and I can’t change this fact. However, I want others to know Hazaribagh as I do, the good and bad of it, and not think of it solely as a Maoist-infested town in eastern India.

So yes, this is why I owe this award to Hazaribagh—the land and its people—for giving me my share of both good and bad experiences. Hazaribagh can, indeed, be acidic. People felt uncertain about my future when I refused to be an engineer, otherwise a norm for science stream senior school boys. But I have no complaints. I am thankful, rather, to the town for questioning my choice because that uneasy interrogation propelled me to work harder. And the more I involved myself with the place, the more I travelled to its interiors, the more aware I became. I loved it more and hated it more. I know it doesn’t answer your question in a straightforward way, but it’s simply because there is no straightforward way for me in the first place. There’s something Hazaribagh and I share which might be esoteric to others. It’s like an inside joke, or a secret, which I cherish. But I hate it as a writer. I consider it a failure on my part—this inability to break this “something” for others to understand.

What a lovely interview! I really enjoyed Mihir’s ‘place enthusiasm’ and his refusal to get bogged down with the future. It would have been nice if the interview had carried a few lines from his poems though.