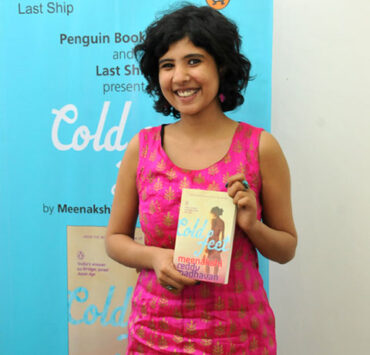

In the literary world, names have a tendency to fade away, but Aditi Rao’s hasn’t. She recently won the Toto Funds the Arts Award for Creative Writing in 2012 after winning the Srinivas Rayaprol Poetry Prize last year. Her poems have been published in journals such as The Four Quarters Magazine, Muse India and Cha: An Asian Literary Journal.

Aditi’s world extends beyond poetry: she is also an essayist, a peace educator, and a teacher. She conducts creative writing and research writing workshops, and works in the arena of social change, particularly in designing education for peace. We spoke to her in an exclusive interview about her experiences at the Sangam House writers’s residency, her writing workshops, and why she feels that the profession of writing is anything but solitary. Read on for excerpts—

Aditi Rao won the Toto Funds the Arts Award for Creative Writing in 2012.

You won the Srinivas Rayaprol Poetry Prize for 2011 and now the Toto Funds the Arts Award for Creative Writing in English for 2013. Does the poet in you feel any different?

The poet in me feels the same, only more public. When I won the Rayaprol last year, I hadn’t yet begun to send work out for publishing, so my readers were mostly friends and family, and an occasional friend of a friend. In starting to share my work with a larger audience mostly in response to solicitations from online journals after the Rayaprol, and in receiving emails from some readers about their responses to particular poems, I’ve begun to enjoy ‘going public’ with my writing. And I’ve been incredibly moved by the support and encouragement from so many quarters, the Rayaprol trust and T.F.A. amongst them—I’m sure that has bolstered my confidence in my words and my willingness to share them.

But ultimately, most of my poems are still written to an ‘audience of one’: a specific individual—dead or alive, friend or stranger—to whom I have something important to say. To that extent, the poet in me is the same, intensely personal being; the major difference is simply that I’ve started being more public with the finished product.

You moved back to Delhi a year-and-a-half ago. We know that places can seep into one’s writing—how has Delhi worked its way into yours?

I’m not entirely sure yet. There are obvious ways, like the physical landscape of the city, especially the archaeological Delhi, starting to show up in my work, as well as the presence of more desi words and images, I think. But that’s not as interesting to me—I’m more interested in seeing how my growing sense of ‘being home’ in one place affects my writing. I’ve often been told how much my work invokes travel and shifting identities, which makes sense given how many places I’ve lived in over the last decade of my life. Now, as I begin to feel at home in one physical space for the first time in many years, I’m curious to see how this more rooted identity will play out in my work. I’m not sure to what extent I’ll be able to see that in my own writing, though—maybe you’ll have to tell me.

I have to tell you, though, that I’ve found lately that some Indian writers and readers think my writing is not “Indian enough”, and some Western ones think it’s “too Indian”. To me, that feels like the right balance!

For the past year, you’ve held writing workshops in your living room, colleges, and workplaces. Could you tell us a little about what that space means to you?

Some writers will tell you that they wished they could just write full-time but that they teach to make ends meet—that isn’t me, not by a long stretch. I love teaching and facilitating workshops, and I feel really lucky to have had so many opportunities to do so in different kinds of spaces over this past year. I’m currently teaching two broad kinds of writing workshops: research writing in academic and think tank spaces, and creative writing in colleges as well as out of my living room. They’ve both been interesting in different ways.

The research writing workshops are giving me such a glimpse into where our education system has failed us. If so many educated adults, well into their academic and professional careers, are still daunted by the idea of coming up with a question about their field, finding the resources to answer it, and being able to communicate that answer to the world, then we have some serious introspection to do about our schools and colleges. But the flip-side of that is that I’ve always been met with great excitement at these workshops; people are eager to develop these skills, and I learn so much while working with them. I’ve always maintained that there’s no better way to learn more about writing than to teach it, but I’m also learning so much about the fields in which my participants’s expertise lies. For instance, last year, I did a series of workshops at the International Food Policy Research Institute (I.F.P.R.I.); I taught skills like reading actively towards literature review, outlining research papers, checking for logic and evidence, and revising. In the process, I also learned so much about nutrition, livestock, and climate-sensitive agriculture technologies. There’s something incredibly enriching about that kind of teaching-learning process.

But it’s the creative writing workshops that have a really special place in my heart, particularly the ones I teach out of my living room over a series of 12 weekends. These workshops started out somewhat on a whim—a friend had been asking me to do something like this, so I made “If I were teaching a creative writing workshop, who would sign up?” my Facebook status for a day, and enough people wrote in for me to consider it seriously. From there on, it’s mostly just been word of mouth.

I’m about to start my fourth group this week, and I’m really excited. Because this workshop is completely my space, I can follow the curriculum and teaching methodologies that work best for me, and I can create the physical ambience that I want, complete with coffee and home-baked brownies! Not being bound by any external set of expected workshop outcomes, I can also allow participants to set their own goals for our time together—some want to work towards writing professionally, some want to reconnect with a hobby, and some simply want a place to relax and enjoy words for one afternoon a week.

So far, I’ve had an age group of 18-55, and professional backgrounds ranging from students, homemakers, editors, N.G.O. workers, lawyers, economists, I.T. professionals, a comic book artist, and P.R. professionals represented in my workshop. Something very exciting happens in that cross-generational, cross-professional exchange of stories and ideas; I think we all stimulate one another to write things that none of us may have written alone. 12 weeks is also long enough for folks to really get to know each other and build a community that feels safe and supportive; having such a community of writers often allows participants to trust their voices and grow in their writing, just as much as the craft elements I teach.

This winter you spent three weeks at the Sangam House writers’s residency. Writers always return touched by the rustic allure of the place. What did the place and the company do for you?

Sangam House was magical. Because I do so many other things professionally, it is rare for me to devote three whole weeks to writing. While I can often manage to write poems in the middle of my everyday life, I found I needed that kind of dedicated time and space, sans distractions, in order to work on a larger project—in this case, pulling together a manuscript of my first book. The process of organising a manuscript demanded holding seventy poems, in various permutations and combinations, in my head at once; I don’t think I could have done that while also juggling various other responsibilities. In that way, Sangam House was crucial to getting that manuscript ready for the world.

“I enormously value and enjoy community in and of itself.”

But I will say that the conversations and relationships that came out of those three weeks are even more important to me than the writing and editing that happened there. I often wrote outdoors during the day, taking breaks to discuss poetry with another poet and translator. Most evenings, after finishing the day’s work, I would go for a long walk or bike ride alone or with another writer. I spent many nights stargazing, or talking well past midnight with other writers at the dining table or in our rooms, sometimes about books and words, sometimes about our lives in general. There’s something about the isolation of that physical space and the distance from everything we consider regular life (family, pets, paychecks, schedules, even cell phone reception!) that allows for a certain intensity and intimacy that is hard to replicate elsewhere.

More simply, Sangam House was also just a lot of fun. Reading particularly bad literature out to each other after lunch, a two a.m. chai-and-Maggi picnic under a meteor shower, baking cakes and brownies in a pressure cooker, long conversations about the Sunday newspaper’s matrimonial ads, managing to find vanilla essence in a tiny Karnataka village, learning about histories and cultures of societies I had never particularly wondered about but now had a close friend from—all of those memories are a huge part of what made the residency so special. Some of these experiences worked their way directly into my writing (at least three new poems that I wrote during this time were directly inspired by them), but many were simply about building friendships and real relationships that will far outlast the time we spent at Sangam House. And to me, these friendships with other writers, across genres, languages, and cultures are ultimately the most important thing I got out of the experience, even if it isn’t always possible to quantify how and why.

You talk a lot about community. How would you respond to the idea that writing is a solitary profession?

Writing is not a solitary profession. Even though the actual job of putting words on paper is a solitary one, the process of being a writer is, for me, a deep engagement with the world and therefore with the people around me. If I were to write only based on the thoughts in my head as I sit alone at a desk, I’d get really bored, really quickly. In order to stay excited and fresh in my work, I need to care about the story of that woman I met on the bus who told me that “the best part about marriage is that you always have someone to hug”, and about that sabziwala in Jaipur who sings to get your attention, and about that child at the airport who is pointing and shouting “Look! The plane is about to crash into the moon!” Inasmuch as my writing self pushes me to engage more deeply with the stories all around me, I think of writing as the opposite of a solitary profession.

Also, in the process of writing, I have come to a deep appreciation for having a community of writers I trust. I once had a wonderful teacher who set up a ‘writing buddy’ system, pairing each of us up with another writer in the class, so we all had that sense of partnership and camaraderie as we wrestled with our words. I found it useful enough and enjoyable enough to continue that informally in my own way. One of my closest friends is a playwright in New York; he and I have developed what we call a “process partnership”—we set up regular conversations specifically to talk about our writing process, working through the obstacles and the joys together, sometimes offering each other feedback on new work, sometimes simply providing a space where the other person can share a story and feel heard. Another friend and I have a private blog where we set ourselves certain writing challenges. Again, we’ll offer each other feedback when requested, although the main aim of the blog isn’t feedback as much as it is holding ourselves accountable as writers. And I know that I often learn what a piece of writing needs just by sharing it with someone, even without the other person saying anything in response.

I also think every writer has stories that she or he is afraid to tell: [stories] that make us feel too vulnerable, too exposed, but that are often our most powerful stories. Having a set of close friends, who are also usually my first readers, allows me to start sharing some of those; I couldn’t go public with some of that writing right away, but I can allow these people whom I trust to read it, and that becomes the first step to sharing it with the world in general. This was also part of why the community at Sangam House became so special to me; I developed that kind of trust with at least one other writer there, and I think that helped both of us find the courage to tell stories we may not have told otherwise.

Ultimately, I guess it’s also just that I enormously value and enjoy community in and of itself. Having this community of writers enriches my writing, but more importantly, as we engage with early drafts of each other’s writing and therefore with each other’s deepest thoughts and feelings, it also enriches my life. What more could I ask for?

You travelled to Sangam House in the winter to write, and to Himachal Pradesh and West Bengal a few months before that. Do poems come to you as you travel? Or is it a process that requires some time and distance to develop?

Images come to me as I travel. There’s something about travel, especially solo travel, that makes one so observant—so aware even of the mundane—that makes things jump out with a certain freshness. When I’m outside a familiar context, I also find myself sitting down to listen to strangers’s stories in ways that I am not always able to do back at home.

So yes, I make notes towards poems on these journeys, but the process of turning those notes into poems usually does require some time and distance (I say usually because I’m yet to discover any hard and fast rules about my writing—sometimes, those notes do become the first draft of a poem on the spot, and sometimes they stay in a file for years).

What’s next for you and your writing?

Well, hopefully the publication of this manuscript I finished at Sangam House, for one. And an attempt at a more disciplined writing life, including a series of quasi-historical poems that I have begun working towards. And more freelance and consultancy projects than you have space for me to list in this interview!