Marjorie Kramer is of the view that there is no such thing as the ‘Anatomy is Destiny’ theory, that women have some inherent feminine quality which encompasses all their works and constitutes a ‘feminine aesthetic’, such as vaginal images.

“Henry Moore does holes as much as Georgia O’Keeffe and Bonnard’s work has a feminine quality… Up to now, feminine sensibility has been slave sensibility.” What Kramer is trying to say is that there is always a need for good art and it should be produced irrespective of the artist’s gender. Landscape, for example, where both the sexes have been more or less in agreement, has been projected beautifully by men and women artists.

The above three paintings are by Georgia O’Keeffe, a part of her Black Iris series. One cannot help but notice the resemblance between the flower and the vagina in these images.

The two main kinds of feminist painting are conscious and unconscious, from the women’s perspective. Unconscious feminist art could be male nudes, self-portraits, portraits, scenes from the domestic life (kitchen) whereas conscious feminist art is borne out of one’s own experience and essentially feminist aesthetic comes out of female consciousness. Such art does not exploit women or portray them to be some sort of weak/man-eating monsters/objects of only sexual desire. Feminist art cannot be in quintessence abstract, it has to convey some sort of progressive truth, has to be socially legible.

As is stated over and over again by feminist art historians and theoreticians, the woman artist tends to directly associate with emotions, which shows very blatantly in her works, and is often misconstrued by the male in the society who tends to judge it on the parameters set out by him. “So if a woman’s work is deeply involved with her feelings as a female it is likely that a man will: (a) approach it in the same way as he does the work of a man; (b) expect ideas which he can apprehend intellectually; (c) disregard as unreal or invalid ideas that do not conform to his conception of reality; and/or (d) be unwilling to experience reality as if he were a woman. (Judy Chicago)” The all-man is generally conditioned to be afraid of the purported feminine feelings and thus there is a common disdain for anything remotely linked with feelings of softness, vulnerability, gentleness, delicacy and so on and so forth. In order to make it into a man’s world, the woman artist is liable to prove that she’s as good as a man, thus often not wanting to associate with the female which is treated as an object.

Critics of feminist art have stated that it is opportunist, reactionary, rooted in biological determinism, and instead of being progressive it is propagandist sharing its ideologies with the political movement of which it is a part. Feminist art is very distinctly different from feminine sensibility. As Pat Mainardi very bluntly put it:

1. Women have got to have something to sell.

2. It had to be something you couldn’t buy from a man but could only get from a woman.

3. It shouldn’t challenge too many of the market’s standards at once but should be similar to what men are doing and collectors want.

4. Female aesthetic should be based on form, not on content, just like everything else in the art world.

Judith Stein counters Mainardi’s claims of feminist art being a regressive thing by differentiating between a ‘liberated’ woman and feminist. The former would compete in a man’s world on his terms and try to create a niche for herself whereas the “feminist sees herself as a part of the broader movement. She understands the implications of sisterhood and Marxism. She does not strive for a bigger piece of the male-defined pie, but rather towards a society where not only all women, but all people are able to define their own existences.” Now, art which comes directly out of a feminist such as this could not be degenerate. Also, one fails to understand why the feminist imageries of rape, childbirth, and cunt paintings are looked down upon. Art need not be beautiful, it could be disturbing and haunting. As long as it leaves an impact on one’s consciousness and is memorable, the purpose is solved and is just as great as any other works by the masters. Often it is considered negative but from the women’s point of view it is quite positive, “an act of truthfulness”.

Publicly showcasing pain and suffering has a therapeutic effect. Also, women, who have been bestowed with the gift of giving life, have been reduced to tools for procreation and this anguish is portrayed though images of ‘labour’ of childbirth and the trials and tribulations of mothering. In order to truly and absolutely liberate themselves and attain closure, feminist artists tend to annihilate themselves. “The feminist iconography of the body often tells us less about essential experiences of being female than about how patriarchy has mapped and controlled the female body and used it as an object of exchange between men,” said Whitney Chadwick.

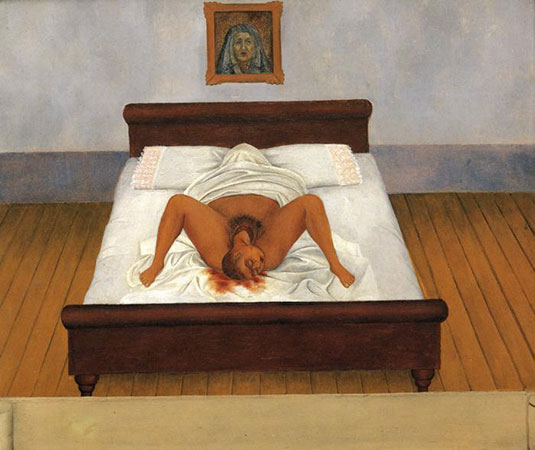

A painting by Frida Kahlo representing child birth, a central theme around which a large part of the feminist movement revolved.

Chadwick adds, “Surrealism offered many women their first glimpse of a world in which creative activity and liberation from family-imposed social expectations might coexist.” The painting above by Frida Kahlo very aptly depicts how painful it is to give life to someone. It is most probable that in this particular painting, the mother died while giving birth. This is hinted at with the face of the mother being covered by a white cloth. It could also be that the painter could not or did not wish to directly show the pain on her face and thus decided to cover it. Another, more personal aspect of it could be the fact that Kahlo longed to have children all her life but could not and her yearning came out through her paintings.

Kahlo is a classic example of marginalisation in terms of location and gender and she worked marvellously well given the circumstances she was presented with. Joan Borsa said that “Critical responses tend to gloss over Kahlo’s complex reworking of the personal, ignoring or minimising her interrogation of sexuality, sexual difference, marginality, cultural identity, female subjectivity, politics and power.” Hayden Herrera, the biographer of Kahlo, tended to overtly romanticise her life: “By the end of the book it has been established that Frida Kahlo’s life revolved around love, marriage, and pain; in short a traditional feminine sphere has been presented.” Her works questions marginal contexts and representations of the body and sexuality and instead of glorifying and celebrating the feminine form she parodies and capsizes the way women have been presented.

According to Shulamith Firestone, “It would take a denial of all cultural tradition for women to produce a ‘true’ female art.” It is not practically possible to create a counter-culture as most of women artists worked within the larger masculine tradition and the aim of the feminist movement is not one of separatist at that. This leaves most historians frustrated and with the only doable alternative of modifying the existing tradition to our own convenience.

In conclusion, one would like to say that feminism in art theory cannot afford to just provide a perspective aiming to improve the structuring of art history. It is greater than that and the myths of a restricted masculine creativity and the inferiority of feminine art stretches beyond and into the ideological level in reproducing the hierarchy between the two sexes. There are differing opinions but more or less feminists are agreed upon the fact that culturally, woman is constructed as the other to the man, who is the norm.

The women artists who have been discussed above such as Keeffe and Kahlo are feminists with a distinct feminine/female aesthetic. The myth of ‘great’ art has been destroyed; it was primarily a bunch of men professionally into painting for generations together, who patted each other on their shoulders since they had nobody else to do it for them. Also, that the theory of biological determinism does not hold true and has been discredited overall and has been replaced by the theory that women are closer to nature as opposed to men, who partook in the formation of culture which came to be dominated by them. Women by far and large were denigrated and labelled as machines for furthering the human race. Female artists were given the illusion of freedom of expression but in actuality were socially restricted to painting the domestic lifestyle. They had to compete in the male-game on male terms and were sidelined in most of cases. But this has come to change over the past few decades with the second wave of feminist movement where the set notions were finally challenged and paintings of artists such as Kahlo, Keeffe, Chicago, Schapiro, etc. were brought to the forefront. Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro spearheaded the movement in art with their Project Womanhouse and since then there was no looking back. Feminist art is still an ongoing process but in many cases has given way to post-feminism.