There are so many primeval experiences that are universal yet remote if one tries to approach them through language. Amruta Patil finds the words and the images; images she calls ‘scaffolding for the text’ to describe these moments.

Whether it’s suggesting that humans have a weakness for cigarettes because of an ancient desire to hold fire between our fingers or understanding Ganga’s drowning of infants as ‘timely culling’, she will find the words. The graphic novel form only makes her prose more effective; you’re moved in the quietest way by the sparse words; like a conversation with the right number of words in it, nothing over, nothing under.

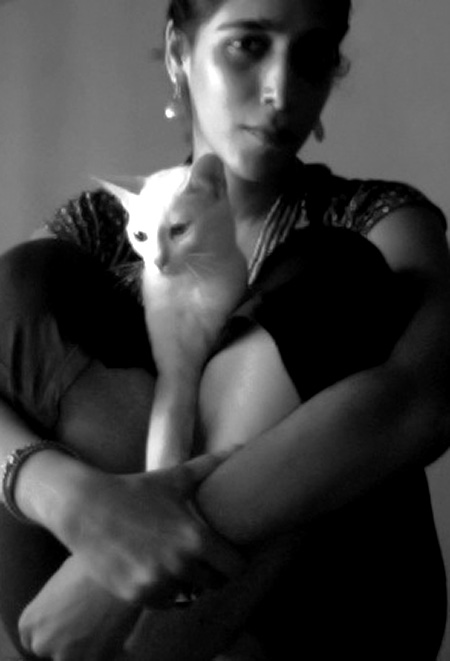

Amruta Patil: An artist and a storyteller.

She’s worn many masks in this lifetime. She’s worked as a schoolteacher, copywriter, and intriguingly enough, as an art museum gallery lecturer. She edits a quarterly print journal called Mindfields that compiles articles about innovative ideas and progressive education, and her visual stories have appeared in journals such as Art Review, TimeOut, and Forbes Life.

Her first book, Kari, was published in 2008. It has since gone on to move people the world over and has been translated into both French and Italian. She is a TED fellow and currently working on Parva, a graphic reworking of the Mahabharata. In a recent interview with Paul Gravett, she described it as the epic about “every human preoccupation under the sun”. The first in this series is Adi Parva: Churning of the Ocean, to be released by HarperCollins this month. Read on for excerpts from an exclusive interview with Ms. Patil, followed by a preview of Adi Parva—

A graphic novelist is both an artist and a storyteller. You’ve said in numerous interviews that it’s the written word you lean towards. Do you see a day in the future where you could create a work with just one of the two mediums?

Yes. I am hoping to do exactly that when the Parva books are done—which would be after a year or two, if everything about world and limb is intact by then. Working sans-image is a bit of a personal challenge. Like cycling without trainer wheels or giving up a security blanket. Without the inflatable armbands of illustration, does my work have what it takes to float?

Is there somewhere in particular that you like to work?

We deserve harmonious settings, but can’t always afford them. I hope India borrows the European tradition of independent artists renting large, beautiful studio space collectively, and working out of it. Except for snatches of time at the art residency abroad, I have never had the financial liberty to be overly picky. In a perfect world, I’d like to work in the Kangra valley; but perfect settings are famous for breeding dysfunction, so its just as well.

So I’ve worked out of the living room of my barsaati in Delhi. I work out of the living room of my apartment in Goa. Not the best thing—to live and work out of the same place—but it’s what I can manage now. To make a distinction between non-work and work, to be ‘in the zone’ despite being just five feet away from rumpled bed clothes, I have a ritual: I always dress with utmost care, down to the correct earrings, even if I am going to interact with zero human beings in the day. There’s something respectful about not being a slouch while you’re around the sanctum of work.

Do you ever discard drawings? How many attempts does it usually take to get a drawing right?

I work fast and furious; mostly, there is no redrawing. It’s interesting you ask this, though. Since Adi Parva is as much a personal journey of striving, as it is Ganga’s narrative about the lunar dynasty, I made a decision early on that I would not discard a single drawing. If something felt wrong, I kept working on it until the paper risked giving way and then I stopped. I had never painted before Adi Parva, so sometimes, even with all that work, certain pages just look like they’re wearing sloppy makeup. But that’s okay. The gawky, the good, the awful, the resolved: it’s all there for the world to see. I offer myself, vulnerable. Sauptik Parva will be better. In any case, in this book (and in any books I will be associated with), the pictures are a scaffolding for the text. Where it’s really at, as far as I am concerned, is in the written.

Kari had an overwhelming response from all over the world. Is releasing a second very different book a daunting idea?

Kari wasn’t a tornado vis-a-vis sales figures, but she did receive an extraordinary amount of love, the sort that I wouldn’t have predicted for her prickly, painfully private little heart. I am fortunate. Kari was the wild card entry that no one expected anything from. It’s easier to reel people in with a personal tale. Adi Parva belongs to our collective wealth, our collective memory—people are going to have more opinions about it, and are quite likely to reject what doesn’t validate their own point of view. Grandiose settings (which is what the setting of epics is assumed to be, though I disagree; I see the setting of mythology as being inside of human beings) seem naturally to evoke resentment, hostility. People are wary of meeting a Brahminical or messianic voice, I guess. Who is to blame them? The world is full of irritating new-agey charlatans.

“I need to cut the umbilical cord the minute the book is in stores.”

Adi Parva (read our review) is deliciously complicated. Retellings of the Indian epics have provoked controversy in the past. With respect to that, how do you think this book will be received?

For my own sake, I need to cut the umbilical cord the minute the book is in stores. If the work is good, it will find its people. If it’s not, it will (and should) tank. Easier said than done; and I’d be such a bad liar if I said there was no pain involved in someone rejecting an egg you’ve squatted on for years. But it is distracting, time-consuming and pointless to decimate one’s heart over things that are not in one’s control any more. Eyes to the horizon. Onward ho.

Could you tell us a little about your artistic influences?

Adi Parva marks the beginning of my relationship with paint and painters. I’ve been feasting on all that is pigment-saturated. Odilon Redon. Paul Gauguin. Amrita Sher-Gil. Folk art from our subcontinent, but also from Mexico. The pages for collage are ripped out from fashion magazines, and the jewel box was an important motif.

The previews for Adi Parva look stunning. In contrast to Kari, colours dominate the illustrations here. Is there a reason for the change?

Kari was rendered predominantly in grey because that is what the protagonist’s state of mind was like. So if you’re willing to share my belief that people are responsible in creating the worlds around them, then you can make the connection as to why Adi Parva had to be vivid instead of dreary. It helped that HarperCollins was willing to put in the money into printing an all-colour book, of course (smiles).

It’s a commonly held belief that writers spend their entire creative lives telling the same story over and over. If that’s true, what common story are Kari and Adi Parva telling?

What a terrifying thought: death-by-monotonous-plotlines! But if one were to consider that there is truth in that statement and dance with it: I’d say that the Kari prototype is very much that of a fledgling Bodhisattva—if she doesn’t slit her vein or jump off a building before attaining some sort of maturity and realisation, that is. There is a terrible bit of purple-prose in Kari (pg. 14) about Ruth “striding towards a flame-coloured calling”. Adi Parva is a mile walked in that direction.

Preview: Adi Parva

Click here to purchase Adi Parva: Churning of the Ocean.

Click here to read our review of Adi Parva: Churning of the Ocean.

Read our June 2010 interview with Amruta Patil at this location.