Rebellion being an undercurrent running beneath the surface of any seemingly homogeneous form of culture, the indie scene has become one of the most forthright and conspicuous forms of subculture of our times. Like many subcultures before and after it which initially rejected the conformist label, indie has gradually come to become a part of the very mainstream which it rebelled against, but is nonetheless a crucial movement in what it signifies and means for cultural philosophy — a pathbreaking effort to tread the unknown and chart out your own territory.

For well over half a century now, independent cinema has provided movie buffs the world over a diverse palate of delights to refine their tastes. Defying the assembly line characteristics of much of popular cinema, with its McDonald’s-like business code (follow the recipe, please millions), the indie cult in cinema has managed to confront and reject the demands of pop culture with a rebellion that is decidedly noteworthy in its defiance. More than the defiance, however, the indie movie cult is significant in the way that it compels audiences to confront truths that are decidedly too uncomfortable to fit the conventional paradigms of more conventional, mainstream movies. More often than not, independent cinema has always been viewed as a cinematic experience which dares to go beyond feeding audiences their regular diet of rehashed stories and mindless sequels of the studio system, and provides them with a ‘true slice of life’.

Indie movies: The road to Oscar fame?

The archetype of an indie movie, at least the way it started out in the West, has always been that of a movie made outside the ubiquitous studio system, not only daring to tackle subjects that were too squeamish to be dealt with by more mainstream studios and filmmakers, but dealing with them in a manner which breathed fresh air into stagnating cinematic attempts. The heydays of indie cinema, the ’80s and the early ’90s, saw the emergence of such directors as Jim Jarmusch, Quentin Tarantino, Spike Lee, the Coen brothers, and Steven Soderbergh, whose films have been pure cinematic delights for the true cinema connoisseur, and whose very names today stand for cinematic excellence of the highest order. David Lynch, one of the Big Daddies of indie, raised the bar with his path-breaking Blue Velvet, and John Waters, with his markedly oddball sense of humour, mocked the traditional staples of studio cinema with gems such as Polyester and Cry-Baby. With the Sundance Film Festival providing a forum for independent filmmakers to showcase their talents to the world, the rise of the indie had truly begun.

It was perhaps the very rise of this interest in indie which has subsequently led to its decline and stagnation. Confronted with a growing base of a moviegoing audience asking for more such movies which did not simply mock their intelligence, the studios realised that ignoring this growing customer base of cinema would be to their own detriment, resulting in the studios creating a number of subsidiaries designed to cash in on the burgeoning demand for such movies. The process, in the end, has resulted in movies that are, by and large, designed to cater to the demands of studios to pitch in for an Oscar nomination, create buzz, and generate cash at the box office. Moreover, the proliferation and popularisation of such movies, combined with the advent of affordable digital technology at the consumer level, meant that there was a resurgence in short films, which of late have actually carried forward the true maverick and unconventional character of indie.

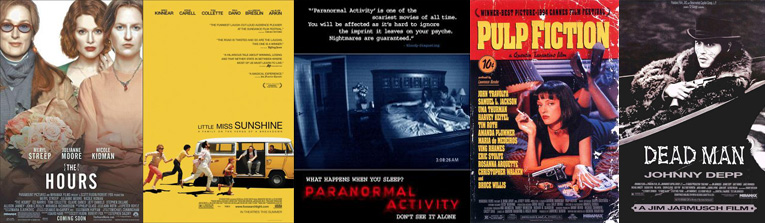

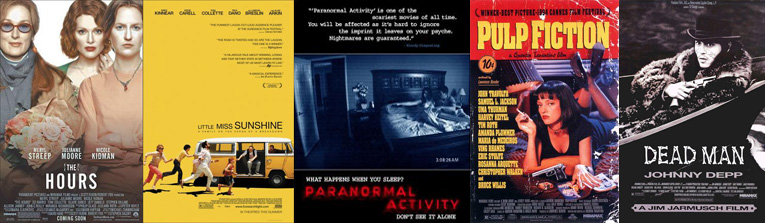

While providing indie moviemakers a bigger canvas was a crucial step in ensuring that their works found the visibility they truly deserved, indie moviemaking by and large seems to have gone the route of a formulaic convention. Most movies seem designed to be tearjerkers simply to tug at the hearts of the Oscar jury and gain attention, without the heart or the soul that truly made them indie in the first place (Case in point: The House of Sand and Fog, The Hours). An indie movie has become synonymous with what many would call the road to Oscar fame, what with fledgling starlets and down-in-the-dumps directors all desperate for an ‘independent movie’ which would gain them credibility and respect in the eyes of their peers. Even as that has ensured that both studios and actors have found routes to bask in the glory of an Oscar, what has been killed in the process is true independent thinking and audacity to go against the grain of conventional wisdom. Unconventionality has been sacrificed at the altar of mercenary ends.

So while these machinations of studios such as Miramax and the efforts of producers such as Harvey Weinstein have actually enabled independent moviemakers to aspire to carve a space for themselves in the crowded Hollywood scene, the very spirit of indie has gone missing from the movies of late. No doubt, the policy of embracing indie did indeed pay rich dividends for the discerning cinema goer for a while — movies such as Pulp Fiction and Good Will Hunting are testimony to the fact. More recently, while such movies like Little Miss Sunshine and Juno have been crowd-pullers as well as critical darlings, they lack the audacity of a Blue Velvet or the surrealism of a Dead Man. The movies of late have been devoid of the spark which made independent movies in their heydays what they were — the edginess and weirdness that characterised such movies as Donnie Darko or Down By Law have been missing from the screens for some time now, with the occasional odd gem like The Station Agent, or the quirky Humpday providing some measure of relief. More often than not, they have gone the route of hiding their pretentiousness and boring content behind the facade and excuse of “real life” — if you want to be entertained, there are other options out there. It is this affectation and refusal to serve audiences what they primarily want — to be entertained and told interesting stories — that has eroded not just audience interest in indie, but also its credibility.

Moreover, the recessionary period of late has ensured that Hollywood’s tolerance of the maverick moviemaker and his vision has been worn down severely, with several indie-flavoured subsidiaries of major studios being forced to scale down productions and lay down staff. In such a scenario, it is no wonder that the reliance on formulaic cinema has increased more than ever before, with studios preferring to bank their box office hopes on a Transformer than pin them onto a daringly original and striking movie such as Precious, one of the dark horses in the running for the Oscars this year.

So where does all this leave the new era of a maverick who just wants to make a heartfelt, truly independent movie, without being bogged down with the problems of where to showcase a movie, how to thwart pirates, use 3D or deal with complexities of Blu-Ray? Small-scale independent film festivals such as SXSW, and the reliance on word-of-mouth, along with internet chatting, podcasting, and blogging have become the alternatives, which are slowly but surely resulting in a new wave of indie film making which has resulted in quirky delights such as Alexander The Great and Goodbye Solo. American backwaters like Austin and Seattle have become the new hotbeds of talent, with independent movies now being supported by the strong community network of small-town America, which has ensured that their budding indie prides find their own footing through movie screenings at the local theatre. The success that was Paranormal Activity resulted from just such a strategy. While there is still a long way to go for indie to return to its glory days, technology and the proliferation of the Internet has ensured that indie movies have at least found a platform to make themselves seen and heard, and it is up to this new wave of moviemakers to see to it that they best use this opportunity, or risk succumbing to the mind-numbing cinema which has deluged the brains of moviegoing audiences for generations.

The new, emerging wave of Indian indie films.

In India too, the problems are not very different. Although there is of course the problem of language and entertaining a multitude of people speaking a plethora of different languages, indie in India has had to struggle not only against the lack of a maverick disposition among filmmakers, but also garnering support and recognition for itself. “Indie” movies in India have a different connotation altogether, as “parallel cinema” which attempts to break free of the stranglehold of the populist Bollywood fare. With its roots harping back to the era of such stalwarts in Indian cinema as Satyajit Ray and Bimal Roy, Indian “indie” has had its heyday in the ’80s, when actors like Smita Patil, Amol Palekar, and Shabana Azmi, along with such directors as Shyam Benegal and Govind Nihalani infused new life and vision into films. From then on, it has been downhill for indie in the country. With burgeoning budgets and poor returns on investments, the indie scene in India was left with lone mavericks like Adoor Gopalakrisknan who dared to face the bleak period with a brave face, taking his movies to independent film festivals abroad and gaining recognition for them in the process. This however, created another dilemma for the indie scene. As poor relatives of the mass-appealing Bollywood masala fare, and devoid of the support of popular moviemakers, unlike their indie counterparts in the West, they were left to fend for themselves in the bleak honours of film festivals, and then quietly fade into oblivion.

Although an attempt at revival was made with the emergence of multiplexes, which allowed the indie movies to compete alongside their Bollywood counterparts, the effort seems to have been mostly a fad. While moviemakers like Aparna Sen, Rituparno Ghosh, Sudhir Mishra, and Onir provided us with delights like Mr. and Mrs. Iyer, Hazaaron Khwahishein Aisi, and My Brother… Nikhil, the passion and the pizzazz which characterised the bold attempts of the ’80s stalwarts with movies such as Swaham and Ankur have fizzled out. With the emergence of “crossover” movies which seem to attempt at pleasing both the commercial-loving audiences as well as those with higher sensibilities, the whole spirit of indie has ebbed out of contemporary Indian cinema.

This is not to say that crossover cinema is bad or there is not the occasional breath of fresh air which infuses new hope. Far from it, crossover cinema has actually kept alive the hope for a revival of indie in its true form, as the trailblazing phenomenon which dares to break free of the shackles of popular cinema which begrudges the audience their slice of critically looking at life. Crossover favourites such as Dev.D and Manorama Six Feet Under might have provided respite from the mundane and done-to-death narratives of more mainstream Indian cinema, yet such movies fail to provide a truly pathbreaking insight into moviemaking, as they lack the vision and the motivation to chart out new territories.

To compound creative issues, there is the ever-present problem of financing and distribution. While things have improved over the years, the fact remains that being an indie filmmaker, especially as you set to chart out your very first movie, is not easy in India. The road ahead is laden with Herculean challenges, not the least of which is the fact that most people seem content with the brainless fare being meted out to them. While the technological incumbrances present in India mean that the options available to indie movie makers in the West are not viable for distribution purposes, what is desperately needed, and certainly within the grasp of Indian moviemakers, is the creative explosion to jumpstart the indie wagon again. Until then, the subculture of rebellious moviemaking and appreciation of the same seems out of reach of Indian audiences.