I just want to say two things about Pachuca. First: Pachuca es una ciudad darks. And second: Rebo, my source, had a centipede named Scully and a dog that took itself out for walks.

About the first, I need to clarify one thing. Pachuca es una ciudad darks roughly translates as Pachuca is a haunted city, but that doesn’t capture the humour contained in the word darks, which came from a meme about Mexico City goths.

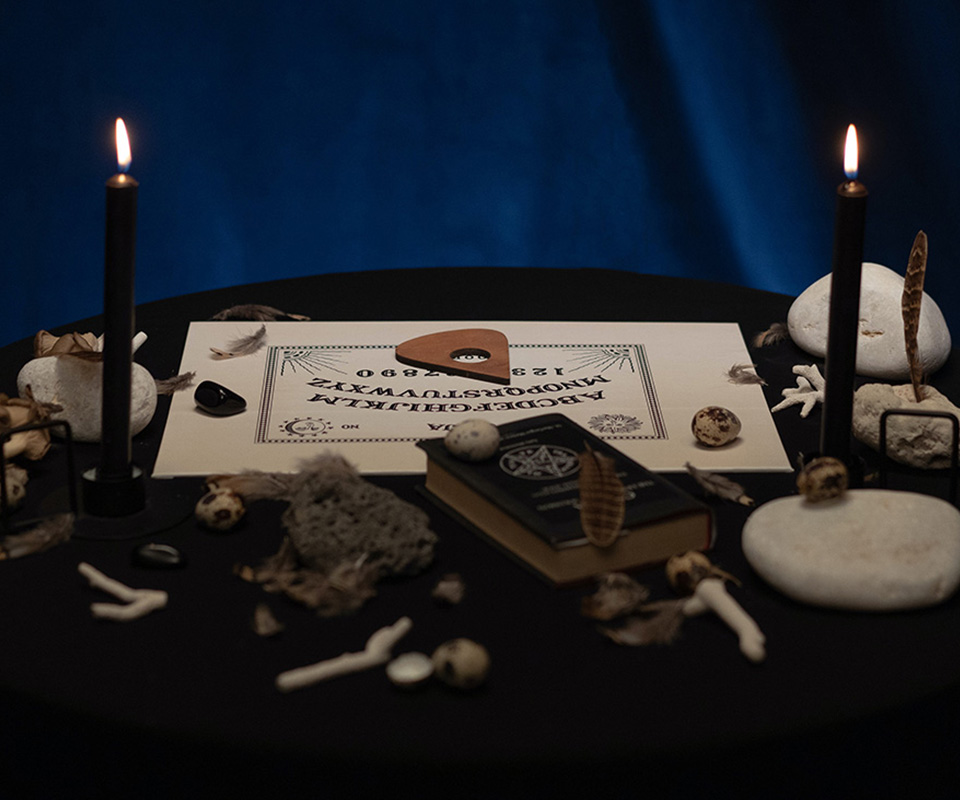

Pachuca is a haunted city for two reasons. First, because the municipal government turned most historic buildings—including a beautiful 20th century cinema—into parking lots. And second, because of how much time Rebo has spent playing ouija board here.

I was not a fan of the ouija board when I arrived at Rebo’s. In fact I had never played it and had no intention of doing so, and so I did two things to prevent him from playing while I was around. First, I asked him to tell me about Pachuca.

He started by telling me the story of one of the leaders of the affordable housing movement, whose name was also Rebo. Rebo was well-loved in Pachuca because he had helped many people keep their homes when the municipal government tried to turn them into parking lots. One day, he went to Mexico City to watch the soccer match between El América and Los Tuzos and, after the match, while drinking at a bar, accidentally got into a fight. He ended up so badly hurt that his opponent thought he was dead and took him to the train tracks outside the city to make it seem like he had gotten run over by a train. Hours later, a train passed over him, but didn’t kill him. When he came back to Pachuca, the municipal government had turned his house into a parking lot. Rebo then painted his whole body gray so nobody would recognize him, and moved to the train station’s awning, where he has lived ever since.

Then he said it was my turn to tell a haunted story. First, I told him about the time I worked as an undercover journalist at Barnacle Farm, writing about the living conditions of seasonal workers. I shared a trailer with Rulo, a self-described nomad who put the electric tea kettle on the stove, and asked me every night why I didn’t want to sleep with him until I decided to just sleep with him so he would stop asking. That strategy didn’t work—Rulo simply tweaked the question: why don’t you want to sleep with me tonight?

The second thing I did to prevent Rebo from playing ouija board while I was around was ask him to play a different game.

— Ouija board is not a board game.

— If it’s a board, and you play it, it’s a board game.

— But you don’t play ouija board, you use the ouija board.

— I see. What if we play a game that has no board, instead of using a board that has no game?

— What game?

— It’s called Twenty Questions.

— Is it about asking questions?

— Yes.

— We could just ask the ouija board.

— The whole point of the game is not to ask the ouija board.

— Why not?

— Yes.

— Is it the ouija board?

— You just said that’s not a game!

But every time there was still the rest of the day, and Rebo knew that I knew that I had to either play ouija board with him or just tell him what I had come to him for, why I had been in Pachuca, staying at his home, for more than a few weeks now. Instead, I did two things.

First I told him about Cándido, who had been to twelve different cities in the U.S., or rather to twelve different prisons in twelve different cities in the U.S. The part of the country Cándido knew best was the section of the desert he walked for days at a time for more than fifteen years, first to try to make a living in El Norte, then to help people from his town get there. Yo he caminado harto. Días en el monte, jamás dejé a nadie tirado—por eso me aprecian aquí. He had crossed the border more times than he could count, but the last time La Migra caught him, he decided not to ever do it again. La mera neta yo soy paisa, le dije a la ley. The first thing he did when he went back to his town was go see the sequoia trees, which are all connected underground.

“Do you know what part of the body the sound comes out of when you sing?”

“The mouth?”

“The bones.”

Then I told him about Omar, the van driver from Oaxaca City down to the coast, whose first words to me were Si se marea, me dice. I vomited three times in the same plastic bag.

— Do you not get carsick anymore?

— ¿Cómo cree? Ésta es la tercera vez en el día que hago esta ruta.

Omar had been on the road for over sixteen hours by then, and still had that trip and one back to complete before he could go home and get some rest.

— Yo crecí en el campo, tengo siete hermanos, pero el campo no da para vivir.

Omar learned to drive in the U.S. He arrived there when he was eighteen, got a job driving people through the Mexico-U.S. border and up into New York City. His boss would send him money to get a new van for every trip because that way La Migra was less suspicious. Omar would take the seats out of the vans in order to fit more people, and would set a support over the wheels to prevent them from getting pushed down by the weight. Then he would drive for days, arrive back in New York, and keep the van and a good amount of money—a lot more than he made now.

But eventually he got caught.

— Me preguntaron quién era mi jefe, que quién conectaba a la raza. Me dijeron que si hablaba me soltaban luego luego. Pero no les dije nada. Les dije que venía yo solo con ellos. Me dijeron que me iban a dar diez años. Para asustarme. El abogado que me estaba ayudando me había dicho que me declarara culpable. Ni madres. Claro, el abogado me lo puso el Estado. Me declaré inocente y salí en seis meses.

That winter, he got a job plowing snow.

— Mi jefe me estuvo llamando para que regresara. Yo le caía bien porque nunca lo eché de cabeza, ni me rajé.

When I finished telling Rebo about Omar, he told me to wait at the kitchen table, and went to get the ouija board. I had one last resource to avoid playing: I asked Rebo to teach me how to sing. First, he told me that teaching was all about choosing the right metaphors. Then he demonstrated—

— Do you know what part of the body the sound comes out of when you sing?

— The mouth?

— The bones.

And made me touch different parts of my own skeleton so I could feel them vibrate with the notes produced by my lungs and my brain.

But to my surprise, he said he preferred it if we just shared more haunted stories. So first I told him about the time I reported on ladderberries, a forest fruit that makes you feel afraid of heights after you eat it.

— Why would they do that?

— That makes no sense, fruit wants to get eaten.

— Fruit doesn’t want anything. Fruit is just fruit.

Then he told me the story of when the municipal government was tearing down the walls of an old woman’s house to build a parking lot and the security guard at the site saw a goblin run away from the property and into the street. The morning after, when the guard woke up, he found his alarm clock completely disassembled. At night, when he came back home after work, the clock was fully put together again. This same event repeated every day for the rest of the guards’ life—his bedside clock disassembled every morning and reassembled again every night.

The next morning when I got up, Rebo was waiting for me in the kitchen with the ouija board all ready on the table. I finally had no option but to play.

I started getting used to the ouija board, just like Rebo started getting used to my presence in the house.

He made me close my eyes and then held my hands. I realized this was a more serious engagement for Rebo than I had given him credit for. The morning light was touching the edge of the kitchen door, and I could feel a slow ray of sun climbing up my back. He put my hands on the planchette and let go. I felt my weight shifting slightly, back and forth, isolated in time from the past and the future, floating in space. Around me I started seeing the train station by my place back in Mexico City. A woman and a child were crouching on the platform, painting each other’s faces to go work in the trains. My vision switched to the inside of the car and I saw them come on. The child told a joke not meant to make people laugh, and then the woman walked down the aisle—una moneda que no afecte su economía. Esta moneda no me va a hacer rica, ni a usted la va hacer pobre.

I opened my eyes and Rebo was calm, his hand on a pen with which he had written down the words I spelled with the planchette.

I started getting used to the ouija board, just like Rebo started getting used to my presence in the house. He would ask, sometimes me and sometimes the ouija board, what I had come to him for, why I was in Pachuca. In response, I would sometimes tell him a haunted story, and sometimes ask him to play a game.

Last night, the ouija board told us that the municipal govern- ment was going to turn the city’s music hall into a parking lot, and there would be one last concert before they demolished everything but the façade. On the walk there, Rebo asked me if I believed in reverse bad memory.

— You mean good memory?

— No, I mean remembering more things than have happened to you.

— I don’t know. I don’t know how to know.

We were late to the concert but still caught a hand moving like a pained tarantula over an upright bass.

Today I asked Rebo to play ouija board with me one last time. Painted all gray, invisible, sitting at the ex-train station’s awning, now a parking lot, we both closed our eyes and put our hands together over the planchette, our fingerprints—the oldest, most democratic printing press—touching.