Akhil Katyal is a bi-lingual poet and translator who grew up in Lucknow and now resides in Delhi. He brings the linguistic complexity of his world into his poems and then sends them back to be read and heard by an audience that is accustomed to speaking in tongues but reading in a single language only.

His research on issues such as Kashmiri politics and gay rights has been published in numerous journals and he has co-authored a critical anthology on American Literature in 2014. In September 2015, his book of poems, Night Charge Extra: Poems, was published by Writers Workshop, Calcutta.

We recently spoke to Katyal about his creative process, the themes he explores in his writing, and his translation work. Read on for excerpts from an exclusive interview with the poet—

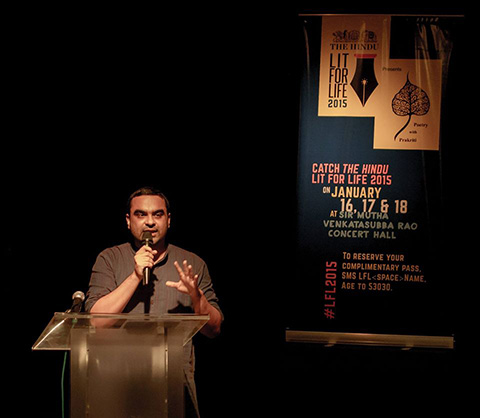

“I send a lot of poems—good and bad—out into the world.” Photograph by Alvin Pang.

You put a lot of poems out into the world—more often than many other writers. I am intrigued—do you set aside time every day to write? Where do you usually write?

That is true. I send a lot of poems—good and bad—out into the world. Agha Shahid Ali used to say of his early poetry years that he used to write “six poems a minute”. I’ve followed his example quite successfully at least as far as quantity is concerned. In fact, poetry as a form can lend itself quite wonderfully to prolificacy. You can write a poem in a day, even in an hour, unlike any other genre. Emily Dickinson wrote nearly 1800 poems in her lifetime. Even the novelist writes something every day but she does not reach her finished form as soon as a poet can. I have the privilege of finishing my unit of work sooner, also because my editing is usually concentrated over a few absolutely manic minutes—in which a word might change ten times before it settles—rather than laid out over drafts that alter over days or weeks.

Quantity is nothing to be proud of but writing poems helps me get by; it ‘dusks my day’, as Mir Taqi Mir would say. But this is tricky, because other than writing a lot I am also a compulsive sharer. The young Shahid might have written six poems a minute but he did not have the poor judgment, like mine, to share all of them or Facebook to do it on. Other than sharing all my poems on my blog, I bomb others’ newsfeeds with them and then wait for the ‘Likes’. I have learned to say entirely without embarrassment that my poems go up on Facebook the night they are written. Sometimes the minute they are written. They reach the book much later. That doesn’t sound very sublime and I am not quite sure what it means for the quality of the verse. But it is really enjoyable to write and share and hear folks on it. I am sure along with some decent fare I also send out half-filth into the world. I’ll stand by both.

Delhi has a strong recurring presence in your poems. What did the years in England do for your writing?

Delhi was the place I came to for college and haven’t left since, other than the three Ph.D. years in London. It was in Delhi that I was away from my family for the first time, which meant unprecedented freedom. It was the first place I really genuinely loitered in, where 2 a.m. became a reasonable time to come back home, the first place where I let ethanol into me. It was the first city in which I had queer friends who took me under their wings and became a wonderful, bumbling sort of family. It was a city of wonderful teachers, long conversations, and late night walks. It was the city of my first kiss and of my first love. During the London years, even as that new city made its claims on me through its riverside and its dark asphalt, its Pakistani food-joints and Nigerian barbers, its drag nights and student parties, its night buses and many other colourful exploits, Delhi remained a point of return, always, pace Eliot, ‘mixing memory and desire’.

Delhi is both in the content of my poems and is itself their habitus. There are poems that start at I.T.O., or near Rajghat at Ring Road, in the Kamani theatre, or at the Indian Oil building in Gautam Nagar, at a bus-stop where I met someone for the last time, or at a street where I first held his hands, in discotheques that first gave shape to desire, or in the metro that let the night sky burn alive with lights. Delhi is a difficult city to love—it is garish, it is rude, its air is grey and heavy, and there are nasty hierarchies you wade through everyday—but once it gets you, once you learn its terms, or how to challenge them if you have to, it is equally difficult to leave.

After all, it is the city of Amrita Pritam, of Mangalesh Dabral, of Ravish Kumar, folks I admire, folks I learn from. It is the city where Agha Shahid Ali studied and taught literature. Where Ambedkar mounted an ambitious constitution. It is the city of Arundhati Roy, of Vrinda Grover, of Nikhil Dey, who keep the horizon lit with hope. And finally, it is the city of Amir Khusro, who is also my neighbour, and whose songs, across centuries, still inebriate the streets, his and mine.

Is there a poem that you return to often? Can you tell us a little about it?

I’ll mention two. Agha Shahid Ali’s two canzones Lenox Hill and After the August Wedding in Lahore, Pakistan. Lenox Hill is a poem he wrote after the death of his mother. It is one of the most powerful poems of the last century. It is the poem in which the death of his mother is spoken of as if in the same breath as the depredations in Kashmir, as if the mourning for the mother is also the mourning for Kashmir. In fact, in both these poems, Shahid has reached the acme of what he said could be a ‘good’ political poem, where the apparently impersonal, large, public subject matter—what India was doing to Kashmir in the ’90s—is appasioned so intensely to one’s heart, that to speak of the loss of Kashmir becomes indistinguishable to speaking of the loss of a lover, or one’s mother. They are both canzones—a very difficult form, but difficult also in its root sense, in that it engages the deepest of our faculties—they are both 65 lines with only five end words for these lines so that a spell is cast by the repetitions. Between these ten words in the two poems—pain, mother, elephant, sing, die, universe, glass, night, and Kashmir (in both poems)—repeating and repeating, Shahid mounts such an elaborate net of loss and beauty that I’m left reeling every time I read them.

Your translations enable the work to travel across time and geography. You are not tied down to the original language, you are willing to adapt to the nuances of the new one. How did you arrive at your current form of translation?

I was from one of those paranoid, elite schools—La Martiniere, Lucknow—where we could be caned for speaking in a language other than English. They fed so much arrogance in us for speaking fluently in English, that some of us used to prance around with our stuttering grasp of Hindi and almost rejoice our not being able to speak well in it. We showed off in front of our colony friends, who belonged to schools that did not take the English-medium-ness very seriously. We paraded our neat diction in front of our parents, who’d ask us, when we were younger, to say ‘bottle’ instead of ‘botal’, ‘rice’ instead of ‘chawal’, an early subliminal training into the pecking order of languages that caught us young. So all in all, we wore this haughtiness associated with English on our sleeves.

But all this was happening alongside an always unmarked, unacknowledged sort of absolute gravitation towards Hindi cinema of the ’90s, a love of the Hindi-Urdu-Punjabi mushairas organised around Diwali that my parents took us to in our Lucknow neighbourhood, a fascination for the Punjabi spoken by my parents to each other, who somehow always spoke to us in a Hindi interspersed with English words. But all this not under the sign of any aspiration, all this was by the by, to be rediscovered later. At school we were still being trained to be snooty English fools.

That was all terrible and stupid. But I realized its stupidity only into the end years of my English literature degree in Delhi University, when I realised—or was made to realise in the classroom, in the staff-room, in the city—that it was an incredible loss to let go of languages that also formed your intimate relation to the world; that gave you your inner blueprint of the world that always exists between languages, not simply in one of them. As the arrogance fed by a colonial Lucknow school receded in Delhi, an entire world of literature and songs, of cinema and poetry, of proverbs and colloquialisms came rushing back again to claim their space. Mangalesh Dabral of Dilli now sat alongside Agha Shahid Ali of Amherst, Bijnor’s Dushyant Kumar alongside the Scottish Jackie Kay, and Hauz Khas’s Amrita Pritam next to Midtown’s Dorothy Parker.

It has been a while since that started happening and now it seems impossible to not be part of this orgy of languages and get off on it every now and then. My world extends to Hindi, English, Urdu, and Punjabi (the last two in the Roman or Devanagari script), so I translate between these languages. Think Langston Hughes or Jackie Kay, Dorothy Parker or Vikram Seth in Hindi, and Amrita Pritam or Mir Taqi Mir, Mangalesh Dabral or Varun Grover in English. Folks tell me my Hindi-to-English is slightly better than my English-to-Hindi but hopefully that will be sorted out soon enough.

Which poet has most recently influenced the way you write?

Agha Shahid Ali, Dorothy Parker, Varun Grover, Rene Sharanya Verma. Shahid has been an important influence to find a restrained and yet eloquent vocabulary for loss. He is insurmountable, of course, but because he wills himself to vulnerability so often in his verse, he seems real enough and it seems possible enough to try and copy him, then fail, sometimes miserably, sometimes moderately, but then try again. His imprint is there in my poems—he might have squirmed hearing this but would still have been encouraging, I safely assume—especially in the long poems I write infrequently. He gave me the elegance of metaphor rather than the tediousness of simile, he gave me a sharper register for pain rather than a cumbersome catalogue of complaints, and finally, he gave me a will to use poetic form which, if done well, often transforms the world into the vessel for one’s emotions rather than the dustbin for one’s self-indulgence.

The New Yorker Dorothy Parker always combined high pathos with self-mocking humour and that is a highly infectious strain. She remains one of my favourite poets to translate. Varun Grover, lyricist and screenplay writer, often brings to my world, an unassuming simplicity that has, latent inside it, the power to shatter—consider man kasturi re, jag dasturi re, baat hui na puri re. Rene Sharanya Verma, the extraordinary Delhi poet, brings joy to the writing of her poems as much as to their performance, something that I really admire and try to emulate.

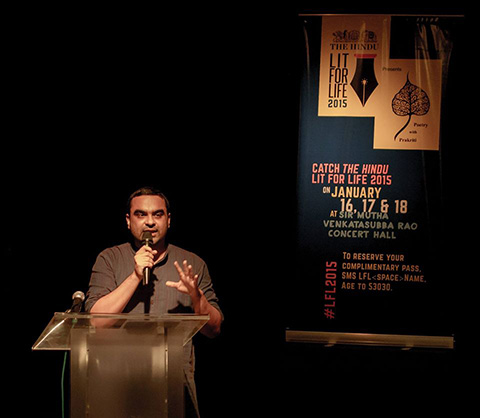

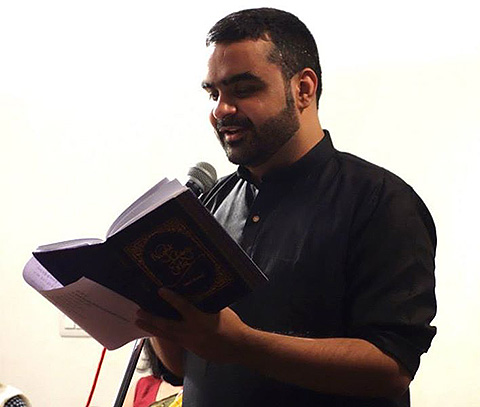

Akhil Katyal reading from Night Charge Extra. Photograph by Inayat Anaita Sabhikhi.

We are moving away from the idea that writers are solitary beings. You are part of a vibrant community of writers. Are there ways in which community is central to you being a writer?

Absolutely. The Delhi poets give me succour, they give me a sense of working in this city together, having a shared narrative of a sort that grounds me here. Some I know well, some I don’t need to know well to have their words take me in. Anannya Dasgupta, Aditi Rao, Vikramaditya Sahai, Aditi Nagrath, Aditi Angiras, Muzaffar Karim, Riya Ray, Mangalesh Dabral, Arun Sagar, Gitanjali Kolanad, Aruni Kashyap, Asad Zaidi, Rene Sharanya Verma, Michael Creighton, Rohit Prakash, Sthira Bhattacharya, Supurna Dasgupta.

They have each, on many occasions, given me a sense that we as poets have a stake in this city, have ways of being in this city, and a meaningful relation with it. That we can do things together. That we can do it in the places for poetry we find together, whether in the India Coffee House or in a D.U. college, whether the park above the Palika parking or a restaurant in Shahpur Jat, whether at Jantar Mantar or in Greater Noida. I explain myself in this city along with my contemporaries. They often do not know how much their words have meant to me, but I always write with them, there’s no other way. A professor at Ambedkar University, Anup Dhar, used the model of prop roots to talk of the autonomous feminist movements of this country. I like that metaphor; we Delhi poets are (and I am sure of it in ideal moments) prop roots. There might have been a central canonical trunk sometime earlier, but that’s passed, and now we’re holding the whole thing up together.

As someone who already prolifically shares, performs, and publishes his poetry, is having a book published an important juncture in your writing life?

I guess it is. I was always told it is. And now I see that the book has brought some new readers, gone to some new places, much like every performance brings some new listeners. The book will travel in circuits and will sit in the shelves, and will lend itself to re-readings, something that the performance could not have, much as, the book wouldn’t have been able to go to Jantar Mantar or to the Constitution Club or a North Campus or a Hauz Khas Village cafe, where the live word moves about. So I guess the book only complements these spaces of poetry rather than spill over them. Talking for myself, I like the poetry flung into the air as much as the poetry stored on the page. But it was cool holding the book in my hands, I won’t deny that. I liked that feeling enough to start preparing my next manuscript.