Imagine losing weight with no effort.

Your cheekbones drop their fleshy curtains, raising your face to the beauty standards you have been made to internalise. Collar bones pierce their way out of your skin, beckoning beautiful pendants to come nest in between. Your stomach sucks in of its own accord, supported by tapering legs that flatter skinny jeans.

This is exactly what happened to me when I was 19, and as a young woman, such an appearance seemed like a dream come true—as it did even in 19th Century England.

As though to help maintain my newfound, seemingly more desirable body, my appetite decreased of its own accord. College assignments began to disguise themselves into an easy excuse for an overenthusiastic student like me to “forget” lunch. I was ready to conquer the world with my bone-popping confidence. In my excitement, I overlooked the feverish chills that crept in every night and made me sweat. They seemed to disappear by the morning, along with my memory of them. The fatigue that I experienced was brushed off as a result of my odd sleeping hours. I was your typically arrogant little college student—constantly biting off more than I could chew and dangerously flirting with my own limits.

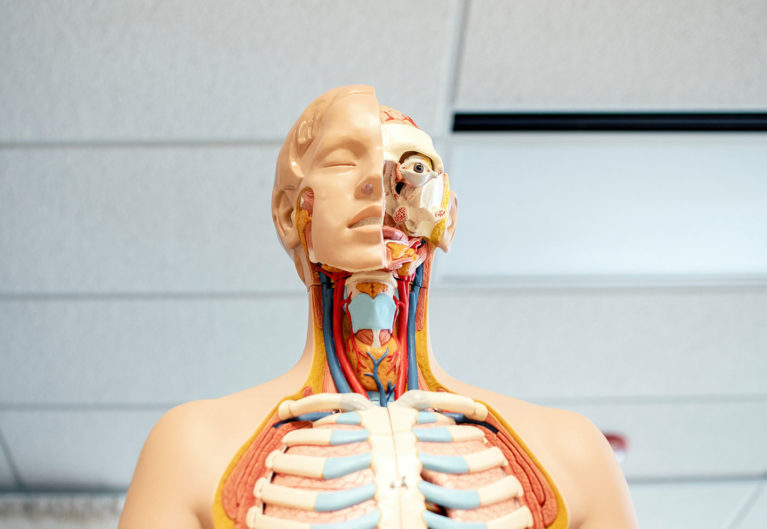

In healthy amounts, however, vanity can do wonders. It’s what helped me spot the lump on my neck as I strolled through a mall in Kerala one day. The doctors called it a swollen lymph node. One biopsy later, it turned out to be an indicator of a losing war my body was waging against latent Tuberculosis (TB). An X-ray revealed tiny white wisps haunting my lungs, making themselves at home. Mycobacterium tuberculosis had made its way to my lymph nodes.

I was prescribed four tablets to be taken daily. These were heavy-duty tablets, and consuming them meant monthly blood tests to ensure that they were not harming my liver—a risky side effect of anti-tuberculosis medication. And much like COVID-19, TB continues to mutate, every new strain proving tougher to defeat than the one that preceded it. Had I been diagnosed with the multi-resistant form of TB, I would also have had to deal with the possibility of more extreme side-effects like hearing loss.

Have you ever felt like a juice box? But instead of a straw it is the needle of a syringe, and instead of juice it is the blood in your veins.

I remember thinking to myself that at least one of the medicines was pretty, as I saw the flaming red and orange capsule that came neatly packed in a bright orange blister pack amidst the other boring white tablets.

The first time I saw reddish-orange urine exit my body, my mind screamed very loudly. It felt like I was standing next to my mind in the washroom stall, watching it scream silently, continuously, without pausing to gasp for air. I waited for it to make sense of things, to figure out what other sicknesses my body had dragged along. Later, images of the red capsules I had ogled at that morning flashed in my mind. I stopped complaining about the white tablets. “Fire and ice,” I thought to myself, as I increased my water intake.

For each day of the six months that the course of medication lasted, I watched the colours in my toilet bowl act like the sun in the sky. At noon, I witnessed the hues of sunrise—bright red blending into a bright orange. By sunset, I saw faint whispers of red drowning in golden yellow, like a hot sunny afternoon. And finally, by night, it was all clear.

The WHO Global Tuberculosis Report 2020 found that tuberculosis had affected 2.64 million Indians in 2019 and claimed nearly 450,000 lives in the country. That is over 1000 deaths due to TB every single day, well before COVID-19 entered the picture. In fact, no country has a higher TB burden than India, which accounts for a quarter of the 10 million global TB cases and 1.4 million TB deaths each year, according to a 2020 study conducted by Rukmini Shrinivasan, Saurabh Rane, and Dr. Madhukar Pai. With the advent of COVID-19, the already limited attention being paid to TB patients has further declined. The healthcare system is too fragile to support more than one disease at a time. As a result, TB patients now have no resources, no access to treatment and medication, and no support.

Today I remember TB as heat. A pathetic, annoying heat vibrating just outside my body. It was my energy slowly ebbing away, leaving me exhausted at the slightest amount of work. Even a little vessel of milk seemed too heavy to lift from the stove. I thought all would be well if I just managed to take my tablets on time. With the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic and the resultant stillness of life, I thought I could sleep away time and the disease, even if it meant skipping important meals like breakfast.

I was wrong. And it was only after almost losing consciousness in the kitchen one evening, as banana fritters were being fried for tea, that I came to understand the importance of nutrition. A well-balanced diet—a minimum of three square meals a day—was mandatory to help me keep up my energy. Along with many fruits, my family also ensured that I ate one boiled egg a day. I would fondly call it ‘Appukuttan’, which is a comforting word to say before and after gobbling down the soft little thing.

By August 2020, after monthly blood tests and regular health check-ups, nutritional diets, clean drinking water, a clean environment, plenty of rest, and a daily supply of medication, I was free from TB. My six-month-long treatment had come to an end, following which I received a bank deposit of ₹500 as part of the Direct Benefit Transfer Scheme by the government towards the nutrition requirements of TB patients. It took that long for the system to register me as a patient, to avail of the scheme. Even if the money had arrived on time, this inadequate amount would not have even begun to cover the costs in today’s economy. By September 2020, a total of ₹1000 had been deposited into my account.

When the rich are cured or protected, the world moves on without realising that it is still very much at risk.

It was a privilege to have recovered smoothly and comfortably, to not have been forced to depend on the government for my recovery. I began to read more about the management of TB in our country and was struck with a feeling that has become increasingly common these days: Survivor’s Guilt. Recovery from TB is a luxury that many cannot afford. This is also the reason why TB is often mistakenly seen as a ‘Poor Man’s Disease’.

I am healthier now, and have realised that being thin is not the same as being healthy. I have a scar on my neck that makes me seem cooler than I am. Curious glances from strangers have also helped me spread awareness. I continue to love my body. But I can’t help but wonder: what if we had been more proactive? If there were more focused drives to eradicate TB among the entire population through early detection and consistent treatment, perhaps I would have been spared this experience. As a country we would have been more equipped to deal with diseases had we paid more attention to this airborne disease that has been around for far too long. For a TB patient, times have always been unprecedented and uncertain.

Stronger mutations will keep coming and they will result in stronger attacks, calling for stronger medications with harsher side-effects. If you see an eerie similarity with the current COVID-19 situation, you have reached the first step. The ugly truth has always been that when the rich are cured or protected, the world moves on without realising that it is still very much at risk.

Sound health demands unity. We need greater awareness and a refusal to forget; to pressure leaders into making quality healthcare more accessible throughout the country with adequate funding. When we make that happen, we can bring about the first wave of change.