A writer, an art critic, a journalist, and an editor all rolled into one, Janice Pariat’s work has appeared in magazines and newspapers as renowned and varied as Eclectica, The Caravan, Nether, Open, and The Asian Age. She founded and edits an online literary journal called Pyrta and contributes to the North-East Blog on IBNLive. Janice graduated from St. Stephen’s College, New Delhi, and went on to study History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London.

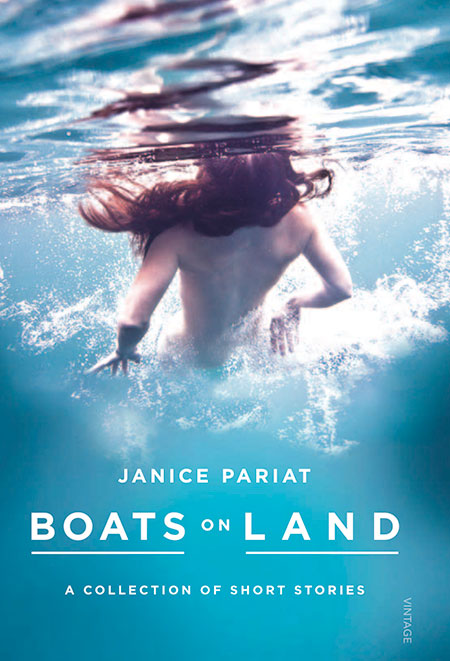

Her poetry and short fiction have appeared in several national publications and her newest collection of short stories, titled Boats on Land, is being released by Random House next month. Boats on Land is inspired by the author’s experience of northeast India, Shillong’s turbulent history, and Khasi folk culture.

The author spoke to us in an exclusive interview about her book, her creative process, and future plans. Read on for excerpts—

“I grew up in a community where, before the ‘civilising effects’ of the Christian missionaries, a largely oral culture flourished.”

It’s generally believed that an author’s first book is semi-autobiographical. Would you say Boats on Land was telling your story?

Since it’s a collection—that would mean many ‘short stories’; 15 to be exact—my life and experiences do inform some details. The cloistered convent school, the sprawling expanse of tea estates, the hum of life in my hometown Shillong. Yet a storyteller must also be a careful listener. I grew up in a community where, before the ‘civilising effects’ of the Christian missionaries, a largely oral culture flourished. Perhaps that’s why Khasis are so terribly fond of stories—mythical, folkloric, scandalous—and make for good storytellers at all sorts of gatherings, funerals, parties, around the fireplace. The stories in Boats on Land are shaped mainly by the narratives of people in and around my life: friends, strangers, family.

2012 has been declared as the year of the short story. Was Boats on Land being an anthology of short stories a conscious decision? Is that your preferred form of writing?

I wasn’t aware of that, so I suppose the short answer is no. I started writing these stories in 2010; some are reworked and even older. I suppose a ‘preferred form of writing’ works well for some—it’s hard to imagine Raymond Carver as a novelist or Dickens as a poet. Yet form is significantly shaped by content. I also write poetry, and have dusty piles of unfinished novels. These stories shaped themselves as they are: as Alice Munro describes them, “worlds seen in a quick, glancing light.”

Could you share any one memory that stands out in the process of writing this book?

There’s a sculpture by Giancarlo Neri called ‘The Writer’: a colossal 30-foot chair and table placed outdoors that he calls a “monument to the loneliness of writing”. Most of my memories consist of pacing floors and staring out windows. Hardly the stuff of pulp fiction. What made me very happy, though, was chancing upon a line that seemed perfect as the opening quote for Boats on Land. In the prologue to his novel The Kingdom of This World, Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier says, “I found the marvelous real with every step,” to describe South America’s unique ‘reality’. It’s a foundational text in the genre of magic realism, and I’d like to (rather ambitiously, some might say) place these stories within a larger context of world literature.

You come from a fairly vibrant and mixed heritage and you’ve lived in many places through your life. Does a particular place inform your writing or is it the oscillation you draw from?

The ‘many places’ would amount to a grand total of three—Delhi, Shillong, London—and they are all woven into my writing. Although less so Delhi, with which I share a rather troubled relationship. Shillong is home only as one of eternal return. A friend once called me a “daughter of colonialism”, and with a mixed Portuguese, British, and Khasi heritage I suppose I am undeniably so. These stories too thrive on cross currents, of people, places, and events, both local and historical. The ‘northeast’ may be seen as a remote, inaccessible place by many, but it is no less shaped by the larger sweeping narratives of world wars, empire, and Christian conversions.

Would it bother you if reviewers and readers alike labelled you a northeastern writer?

Labels often say more about the people doing the labelling rather than the one being labelled. What would it mean to be a ‘northeastern’ writer? Or a ‘north Indian’ writer? I’m not sure, really. The stories are mostly set in Shillong, Cherrapunjee, and pockets of Assam, which fall within the ‘northeast’ region; they are steeped in the folklore, superstition, and political disquiet of these places; but they also strive to be funny, heartbreaking, poignant, and perceptive, all those things that lift a work up into something more universal and gracious.

You’ve just finished an art history course at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London. What’s next for you, your career, your writing?

Conflate the two: write a book on art, create a book that’s a work of art. Perhaps follow Canadian artist Guy Laramee and carve up rare, old books and annoy every single librarian in the world. Honestly, though, I’m intrigued by the novella. So many of my favourite books—The Great Gatsby, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, On Chesil Beach—are exquisite little jewels, crafted like beautiful pieces of sculpture. It would be a challenge, to achieve that precarious balance between short story and novel.

I am actually pretty excited for this book.