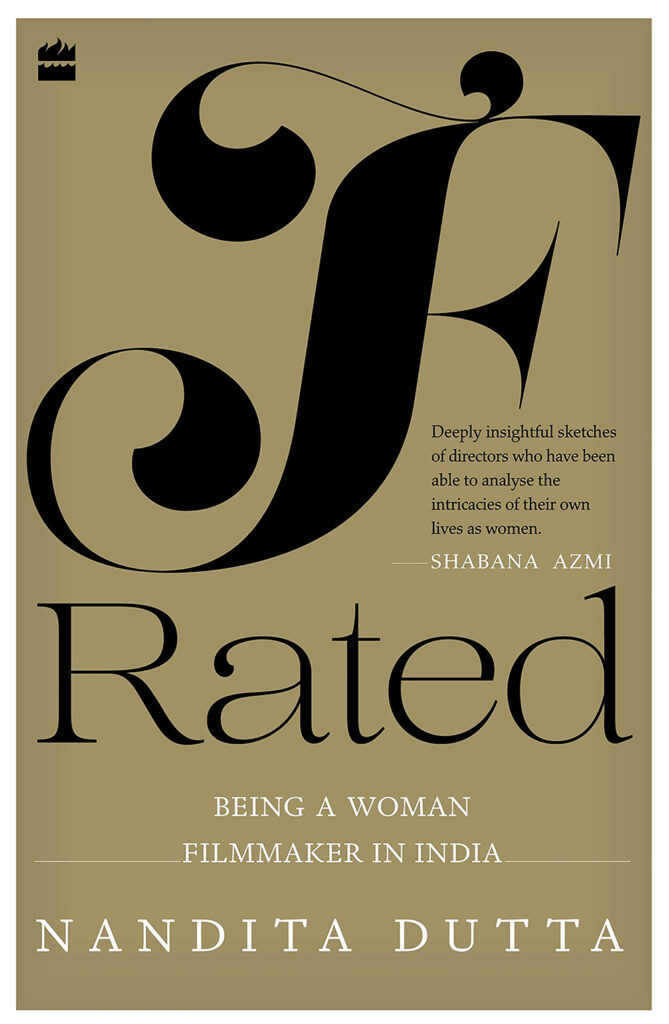

Nandita Dutta’s F-Rated is a book that examines Indian filmmaking through the eyes of eleven women directors who have been central to the industry across decades.

Dutta speaks with influential filmmakers from Farah Khan to Mira Nair and Alankrita Shrivastava about being leaders in a male-dominated field, their common challenges, and the ways in which their paths have diverged. Dutta, who works at the Centre for Studies in Gender and Sexuality at Ashoka University, interviews these women while also incorporating her own analyses of their films and their relationships with feminism in the book. The result is an illuminating and satisfying read filled with intimate details and thoughtful critiques of the state of filmmaking in India today.

Read on for an interview with the author—

In the introduction, you mention that several women you were interviewing withdrew halfway through, saying that they wanted to move beyond gender. Others were reluctant to be called “women filmmakers”. What do you make of this resistance? Did you get a sense that they worried it would be harmful to their careers to be called women filmmakers, or that they might be taken less seriously?

There is definitely that element of wanting to dissociate themselves from the “woman filmmaker” tag because it might make them seem like lesser beings in the filmmaking ecosystem. However, this is a complex question. So, one aspect of it is that they do not want to risk their hard-earned places by being pigeonholed into this category of women filmmakers—the assumption then is that they would only make a certain kind of film that wouldn’t be of interest to a wider audience. It is a vicious cycle, which makes women really wary of labels.

Having said that, some women also resisted the label as they hadn’t really thought hard about how gender affects their professional lives, and for some others, they don’t want the spotlight to be on their gender because it seems like an unnecessary distraction from the kind of work they are doing, which is also a valid concern.

“We have to consciously and constantly challenge our deep-seated cultural conditioning that male stories and experiences are the default.”

There’s a cliché of the solitary artistic genius in filmmaking, but a number of women you spoke with rejected that idea, including Aparna Sen and Shonali Bose. They say filmmaking isn’t separate from their ordinary lives— there isn’t a need to compartmentalise. What do you think about their approach? What are your thoughts on the gender element?

When women speak against compartmentalising, what they are also implying is that they simply do not have the luxury to compartmentalise. Now, history is full of examples of men who were solitary artistic geniuses, but let me give you an example which is closer to home. A friend recently sent me an interview of Sanjay Leela Bhansali, one of the few he gave after Padmaavat, where he holds forth on how he needs solitude in order to create, which is why he does not even talk to the media. While that narrative is alluring, women who are in caregiving roles simply cannot afford to cut themselves off from the world. You’ll read more than one account in F-Rated of women with babies who used whatever little wiggle room they had early in the morning or late at night to write their scripts. That is the reality of being a mother and a filmmaker, and we need to shine the spotlight on it. As for men, I feel a little tired of them not acknowledging the care work of women—paid or unpaid—that enables their solitary genius.

Were there common themes from your conversations that you weren’t expecting? Anything that really surprised you?

Yes; I wasn’t expecting women to talk at length about the difficulties of managing filmmaking with motherhood. Especially as someone who is not particularly keen on marriage and motherhood, I think I too had this binary in my mind, of the artist and the mother. But irrespective of my personal beliefs, the reality is that many women want both, and are sold the myth that they can easily have both. So, in filmmaking, as in any other profession in this world, the most challenging point in a woman’s career arrives when she decides to have a child. However, unlike other professions, filmmaking is so mired in glamour that nobody wants to talk about these mundane but very real challenges.

You reference a 2017 survey by Oxfam India showing that 30% of males said they would not watch a film with a female lead, and 90% saying they wouldn’t watch an all-female cast. Why do you think that is the case? What would it take for people of all genders to support specifically female-centric films?

That’s a very difficult question. As viewers, I think it will take a phenomenal shift in our gaze. We have to consciously and constantly challenge our deep-seated cultural conditioning that male stories and experiences are the default. We have to seek out more female-centric content. And we have to be patient with it, since female-centric is not a gold star in itself. For every Lipstick Under My Burkha, there will also be a Veere Di Wedding.

The final interview places Alankrita Shrivastava in a category of young filmmakers that are here to shake things up. To you, what makes these filmmakers unique and boundary pushing? What do you think about their approach to the female gaze?

I think pretty much everyone profiled in the book is trying to shake things up. Especially with the younger lot of women filmmakers, you will notice that they are choosing to tell unconventional stories and imbuing their female characters with agency, which goes deeper than portraying them as someone who has the freedom to drink and smoke. While their female characters are well-rounded and unabashed about their desires, their male characters are also more sensitive and empathetic. And empathy is what is central to the female gaze.

“Empathy is what is central to the female gaze.”

Many of the filmmakers discuss the challenges they face when trying to finance their films, even after they have proven themselves. Some, including Alankrita Shrivastava, prefer the creative control that comes from small budgets. Do you see a path forward for women to have better access to funding while also telling the stories they want to tell?

I have grappled with this question quite a bit. Many women want to keep working with smaller budgets because that gives them a lot of creative freedom. With bigger budgets comes bigger responsibility, which might blunt their edges. But then, that creates a vicious cycle, because the common perception becomes that women can’t handle big budgets. With the exception of Farah Khan and Zoya Akhtar, there aren’t any women working with the kind of budgets men usually work with. The only way forward is for production houses to make a conscious effort to invest into female directors, to choose women directors for big-budget projects. However, I think what’s more important is to have a critical mass. So, we need more women directing films, irrespective of the budgets.

You spoke to a range of filmmakers, some of whom entered Bollywood decades ago, and others just starting off. What have been the biggest changes over time? Is there any cause for hope for upcoming women filmmakers in the Indian film industry?

I am tempted to quote Mira Nair here, who said at an event put together by Women in Film Los Angeles that we cannot afford to mistake the passage of time as progress. While Bollywood seems to have warmed up to female-centric content, I don’t see any difference in the number of women filmmakers getting to direct films. Or at least, the rise in numbers has been very, very small. I don’t have any easy answers to your question on hope, but I have tried to talk about the structural issues at play in my book.