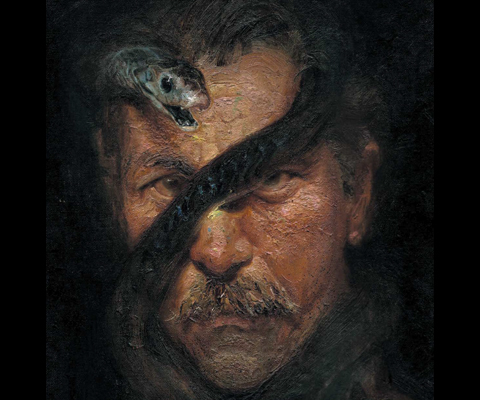

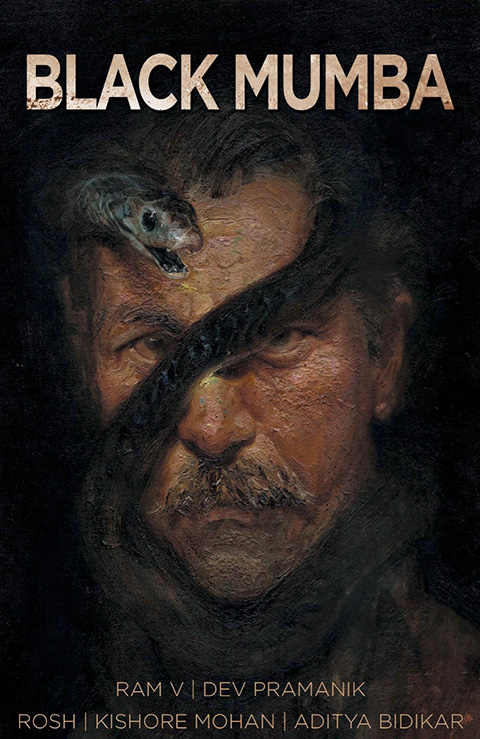

There is a certain sense of trepidation and intrigue that grips you almost instantly when you begin reading Black Mumba. A crowdfunded noir graphic novel created and written by Ram Venkatesan (author of the Aghori series), Black Mumba is characterised by swathes of ink and layered narratives that showcase a few different, dark aspects of Mumbai (thus earning the ‘black’ in its title).

The book is made up of four graphic stories: It’s a Wonderful World, The Witch of Boria House (both illustrated by Devmalya Pramanik), Rats in the Dark (illustrated by by Roshan Kurichiyanil), and Dead Rain (illustrated by Kishore Mohan). The lettering for the stories has been done by Aditya Bidikar and Tomas Marijanovic. Suffice to say, the team behind the book is an extremely talented one and their collective efforts have culminated into this singularly brilliant graphic novel.

In the world of Black Mumba, we see Mumbai through the eyes of Dev and Beri, enforcers of the law; a law that is so elastic that it’s almost a personal moral prerogative for each of them to act. Mumba, no matter how black she gets, has a particular ‘essence’ that is never really lost for those who have fallen in love with the city. It is rare to find such a take on Mumbai, especially in the graphic novel genre.

In an extensive and exclusive interview, Ram Venkatesan and Kishore Mohan talk to us about the finer points of Black Mumba: what inspired the project, the stories that make up the book, and the process of putting together a graphic novel such as this. Read on for excerpts—

What inspired such a dystopian take on Mumbai?

Ram: I don’t think it is any more or less dystopian than the reality of Mumbai for a lot of people. I think that economic and class divisions in India are so incredibly stark that often there are multiple realities in a city like Mumbai depending on what part of society you come from. I’ve had the opportunity to occasionally glimpse these points of view during my time in the city and so the stories reflect that. The medium and the choice of genre supplements the narrative, of course. But the narrative choices came first. The chicken did in fact precede this particular egg.

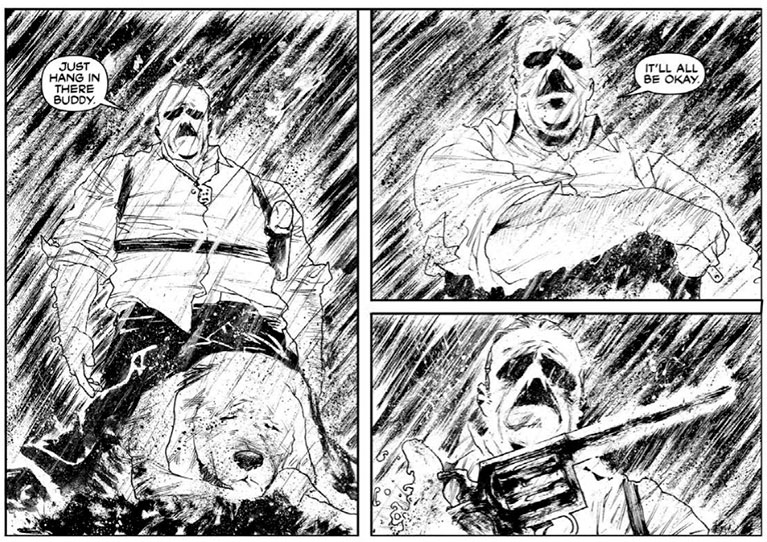

Kishore: To add to what Ram said, especially in my story (Dead Rain), the incessant rain does add to the dystopian mood that the stories have unintentionally acquired. Beneath all its seductiveness, the Mumbai in Black Mumba is just about as desolate and as sentient as the real city is.

How did you go about putting together the team for this project?

Ram: Ahh, that, I think would be a rather convoluted story in itself. To put it simply, I first encountered Kishore and Rosh during their time with Libera Artisti at a Comic Con in Mumbai. A couple of years later, I approached Kishore to work on a 12-page short story with me for an American indie press anthology. Of course, we’d kept in touch and met once or twice by then. The rest of Black Mumba germinated from there. I met Devmalya via the general comics circle in India following my work with Aghori. Most of our interaction was over the Web but we discovered that we had a lot of common influences. The first time I actually met him was after Black Mumba was finished. And now we’re working on a top-secret project!

You have interestingly chosen the policeman—a figure that embodies both authority and is also a subject of hatred (generalised or otherwise)—as your narrator. What was the idea behind choosing such a figure?

Ram: That’s a really good question. It is partly a genre trope of course. The policeman as narrative voice in a crime noir setting—we’ve seen that before. But I felt it had only rarely been done in an Indian context with any sort of subtlety. I’m also a big fan of the ’80s-’90s Indian crime films. Nayakan, Parinda, and it’s younger cousins like Satya and more recently Ab Tak Chappan. I feel Dev is a natural evolution of the morally distressed/ ambiguous characters from flicks like that.

On the question of being a subject of hatred or an authority figure, I think those are institutional traits in India. We examine Dev more as an individual in these stories rather than a product of his institution. He was power in society, certainly, and it lends him agency and the ability to drive the narrative with his choices but his institution doesn’t really feature in the stories beyond that. I’d like to believe that there are still individuals interested in helping others and protecting vulnerable people even if the institution in itself has fallen prey to apathy and corruption.

For me, Mumba as the embodiment of the city was a sheer delight to observe. What is your imagination of Mumbai? Is it mirrored in the novel?

Ram: I think so, and I’m so happy that Mumba worked as a character. My picture of Mumbai is only an amalgamation of my experiences of the city. As a place, I’ve never understood its romance or people who swear by the idea that it is the greatest Indian city. It always struck me as a place that was in love with its younger self. Someone who looks at a photograph of themselves as a 20-year-old and romanticises the nostalgia of the good old days while they fall apart in the present. I think this reflects in all the stories, more through the visuals than anything else. Today’s Mumbai is an unforgiving place in many ways. Stark in its treatment of people. Air-conditioned cars streaming past crowds of nameless people sleeping rough on a sidewalk that forgets them the moment they leave. We embrace this is a reality, we don’t question it. The person who sleeps on the sidewalk doesn’t question it. What does that say about us, about the city? Is that a romantic thing?

And yet it is a place you cannot fall out of love with. Because it sparkles with life in pockets. Whether it’s shuttling around eating Chinese food at four a.m. in some cranny only you know of, or finding the only place with good Irani chai and realising that you’re sitting in a building that’s centuries old. Or eating bhakri in a chawl at the house of a friend you used to play cricket with. A city is also a sum of its people. And Mumbai’s people—the ones who roam its streets, not just paved ones lined with shopping windows but the tiny single-lanes lined with paanwalas and tyre repair shops—they sparkle with life and love, for me.

Tell us about the photographs that prefix every story in the book: how do they supplement the narrative?

Ram: The photographs were an instinctive choice, really. It’s easy to deny the veracity of a place when you see it illustrated. Is it real or is it just ink on a page? As storytellers you use that to bend reality, to dress up the truth. But street photography is more firmly rooted in a place. So I felt they added a layer of truth to the stories. The photographs are from a couple of friends who’ve been doing the kind of street photography that is truly explorative of Mumbai, not clichéd shots of Marine Drive or the Sealink. So when the idea first popped into my head, we ran with it. I approached them and got the pictures that I felt were in keeping with the tone of the story. As to how each photograph relates to the story it precedes, it does so with subtlety and to discuss that would negate it.

Keeping in mind books, novels, and other art forms that have captured the city, what do you think is the dominant narrative as far as Mumbai is concerned? Does your graphic novel strive to deviate?

Ram: This is a complicated question. I think there are multiple narratives with Mumbai to simplify that into one dominant narrative would be disservice to all the fictionalised versions of Mumbai that do exist out there. But I do feel that the narratives of Mumbai have become disjointed. There’s a way the Indian popular narrative looks at Mumbai. There’s a way the rest of the world looks at Mumbai. There’s the young adult perspective of Mumbai, and so on. There are more nuanced and more observant narratives but they’re rare. I don’t think the narrative of the city in Black Mumba is in reaction to any single narrative. It deviates from more common narratives in that it is a relatively under-explored way of looking at the city, as a dark thing that has its own personality, flaws, and victories. We try to categories cities as developed or progressive or poverty-stricken or corrupt, whereas a city like Mumbai suffers from all of these things and finds both victories and losses in dealing with these things. Cities are like people—they’re complicated and we should stop trying to put them into neat boxes.

Ram Venkatesan and Kishore Mohan

What other media did you derive inspiration from when creating Black Mumba?

Kishore: As far as the artistic process goes, I ended up choosing a visual language that I felt would put the reader in the exact state of mind that Ram wanted them to be at each point in the story. The art style I’ve used in Black Mumba is very different from the ones I’ve used in my previous works. Calling it film noir would be an over simplification, but noir comics like Torpedo (Jordi Bernet) and Blacksad (Juanjo Guarnido) were definitely on my mood-board. There is a constant sense of foreboding throughout the story that felt almost supernatural, and I had to make sure that the elements that I chose to compose each frame subtly hinted that something darker lurked right around the corner. It’s like that ominous musical note you hear in a horror flick when the dog runs up the stairs to inspect the strange sounds. You hear that note and you know instantly that Timmy isn’t coming back. What happens between the frames happens entirely inside the reader’s head and that, in fact, is where the real magic of this medium is supposed to happen.

Ram: Yeah, I think the noir influence is obvious. Old ’40s Bogart films and Hitchcock were my touchstones for creating scenes and using visual cues. In terms of comics, I learned from reading Azarello and Lemire (apart from the staples of Moore, Morrison, Gaiman). As for the literary influences, the idea for Black Mumba germinated after a reading of Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy, although the content and subject matter is nowhere near Auster’s work.

The themes and imagery found in this novel are quite experimental and might be too bold for most people. At the same time, however, the novel was crowdfunded to avoid compromises. What was behind that decision? What implications does it have for work that needs to come out as is, regardless of public demand?

Ram: See, I think even you notice the contradiction at the very beginning of your question. I think it is not the creator’s place to judge what is too experimental for ‘most people’ (which in itself is a dubious term). It assumes that readers are some sort of hive mind that will react to formulas predictably. This might be the way business entities might think because it behooves them to seek safety and predictability in the content they put out. But as a creator I have tremendous respect for readers and none of the need to be profitable at the cost of my own creative desires. Numbers beyond whatever lets me continue to make books and live decently, are pointless. I think people are fundamentally open to new things and curious and enthused by things that are different. Good stories can be told without retreating to the safety of established narratives. The fact that Black Mumba found such backing and support not only from India but also from places where people are curious about comics from India/ Mumbai only goes to show that people react to good stories, regardless of who they are and where they come from.

As for the process of crowdfunding, it was tremendous. The sheer amount of interest and support we got was incredibly heartwarming. I had not imagined that we would receive the kind of backing we did. I’d imagined the project barely making its funding. Instead, we shot past that mark in just five days.

The implications of this are just the same as what they have been before. As a creator your job is to tell the story you want to tell, how you want to tell it. Pursue that and tell a good story and put in the work—things will work out. If anything, the distance between a creator and his/ her audience has never been shorter than it is today.

What was the work dynamic like within your team of contributors? Given that the team of artists has come together from all over India, knowing that they are also acclaimed professionals in their own right and have their own projects and work to take care of, it couldn’t have been the easiest of tasks.

Ram: I think the premise of the project enthused everyone. I remember reactions from Kishore, Devmalya, Rosh, and Aditya, when they saw the stories and that was all I needed to know that we’d get this book done. Then it was only a matter of schedules and time. It takes me a short time to write a script compared to the time it takes for the artist to illustrate the whole thing. So I was very patient but also always enthusiastic. I have to say all of the guys were the same with their stories. I know Kishore did some pages on the go while travelling between projects for his work with the studio. Rosh did this between projects. Devmalya did this while he was working on books for international publishers. But at no point was their interest or enthusiasm in question. That’s all I needed!

Most of the interaction happened over the web. Skype chats and emails and such. These guys are total pros. They all know what they’re doing when it comes to making comics. In fact I learned a lot from them throughout the process.