Can something be animated, yet unchanging? The paradox may seem whimsical—rhetorical even—but for Richard Linklater, it has been a substantial cinematic motif.

The filmmaker has never orchestrated sudden growth for the sake of voyeurism, instead taking 20 years to give us this century’s most full-fledged romance in the Before trilogy. It is with this attention to the moment, and not to progression, that he also created the most ebulliently real high school movie of all time—Dazed and Confused.

Literature and cinema centred around young to-be-adults is replete with extraordinary stories, but few 17-year-olds witness that much action. Truly, if there is ever such a thing that is not obsolescent, it’s being 17 and harmlessly unoccupied. It isn’t considered discourteous or termed as ‘talking back’ when you voice your opinion—in fact it is encouraged—almost as if you have to prove fifteen years of formal education with your succinct verbiage. Fresh, out-of-uniform discordancy is thought of as age-appropriate, cute even, and not much is expected from you except consistent school grades.

Really, not much happens to you at 17; you happen to life.

Richard Linklater’s oeuvre reflects his uncanny comprehension of what it means to grow up, fledgling and uncertain.

Few people know this better than Richard Linklater. The American filmmaker’s oeuvre reflects his uncanny comprehension of what it means to grow up, fledgling and uncertain. His last movie, the Oscar-nominated Boyhood was an unidealistic chronology of growing, observing, and changing. But for those who’ve sadly remained oblivious to his work, Linklater has always had the ability to look at stories of regular people as an insider, not as a bystander looking in, as most filmmakers often do. There is a certain intimacy that comes to the fore watching a Linklater film—the characters you know and recognise live with you long after, and the story, or the lack of it, often hits home. And if you had to pick one film that lays bare the aesthetic to Linklater’s storytelling technique, it has to be Dazed and Confused.

In 1991, a plotless, arbitrary film by the name of Slacker launched an Austin-based moviemaker to the forefront of American cinema. Rare was the style to have a movie with seemingly random occurrences without so much as a story, and rarer still for a filmmaker to have attempted this with his second film itself. For the creative members of the Austin community, Richard Linklater had already become a distinctive cinematic voice. Having incorporated the non-progressive, un-plotted storyline from his first movie It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books, it had become certain that Linklater was not as much obsessed with stories and their triggers, but more with narratives, characters, and their inherent humanism. None of this would become more established than with the release of Dazed and Confused in 1993.

… which brings us back to being 17 and wavering.

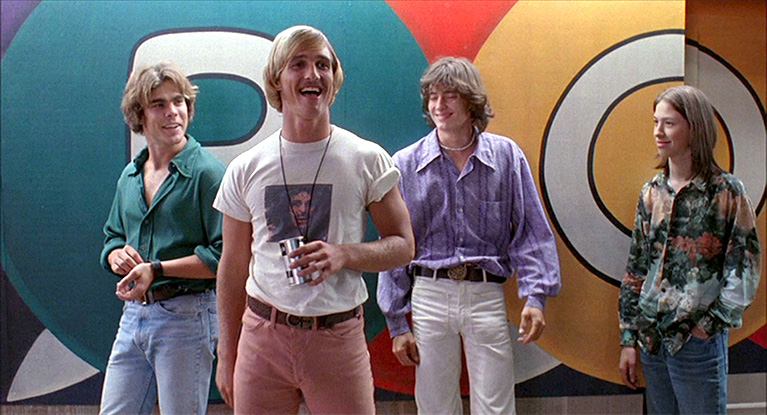

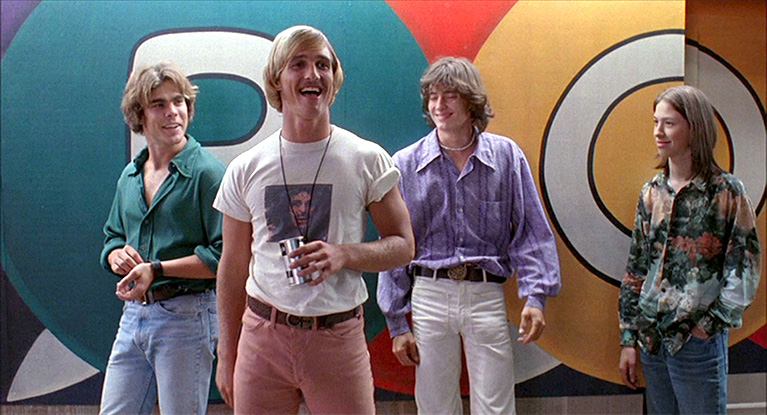

Dazed and Confused was based upon a day in the lives of a bunch of 17-year-olds in 1976—the last day of junior high—and little else. Armed with debauched assertiveness, the upcoming seniors rag and haze the incoming freshmen, have their party busted by poor timing and an unrelenting set of parents, and hit a local field for an impromptu overnight session, helped along by alcohol and marjiuana. They drive around town, kiss each other and chug lots of beer. In the midst of the day’s endless licentiousness would be two central protagonists—Mitch Kramer and Randall ‘Pink’ Floyd. With Mitch aiming to and succeeding by exacting revenge from his hazer—a particularly douchey Ben Affleck—it is Pink who continues to muse over the movie’s pertinent core argument.

In the era of Woodstock, Led Zeppelin, and Aerosmith, it was considered modish to rebel against the system. While the movie’s entire breadth of eccentric characters would be challenging social shackles in their own way, Pink’s rebellion would come in the form of refusing to sign a form that would have him pledge against drug consumption. Truly, if there is ever something that changes from the first few frames to the last, it is Pink voicing this very opinion. Despite being assured of his stance the moment he is handed the form by his Coach, that decision is the one true progression the movie awards you with.

Dazed and Confused remains, to this day, an ethological perception of being young and idealistic.

How did a movie that didn’t really have much to say resonate with an entire generation? For, despite being based in the ’70s, the movie wasn’t simply an insight into the lives of hippy-esque times, but remains, to this day, an ethological perception of being young and idealistic. The characters in Dazed and Confused seem to be conspicuous about what they know, as they exchange existential truths and conspiracy theories with hysterical assuredness. As you watch, you begin to question all you knew at 17 that you could be so sure about. Not enough, certainly. Perhaps that’s why the perceived ‘coolest’ character in the film—a graduate in his twenties (giving birth to Matthew McConaughey’s iconic catchphrase ‘Alright, alright, alright’), who hangs around as some sort of a messiah around the kids—is truly the most depressing for believing that life at 17 is the best it’s going to get, because while we know that it isn’t, we’re constantly afraid that it might just be.

It is his ability to flesh out metaphysical truths that echo with every morbidly indecisive adult that makes Richard Linklater a truly special filmmaker. He continued to explore plotless conversations and relationships in some of his most compelling work after Dazed—in the Before trilogy, SubUrbia, Waking Life, and Boyhood, before succumbing to the charm of rendering Dazed and Confused‘s spiritual sequel in the form of Everybody Wants Some!!. You’re not living the best times of your life, you’re spending most of your time anxiously awaiting the best times. Linklater does not document this despondency, but instead exposes the extraordinary truths one encounters when waiting for something crucial to happen. He understands that the all-too-romanticised plotlines of movies are escapist, and that the real world is far too boring for that.