In 1940, Superman flew to the Siegfried Line, the defensive line built by Hitler’s forces against France, ripped apart the tanks and fortification and called out to the French forces, “Come and get ‘em”.

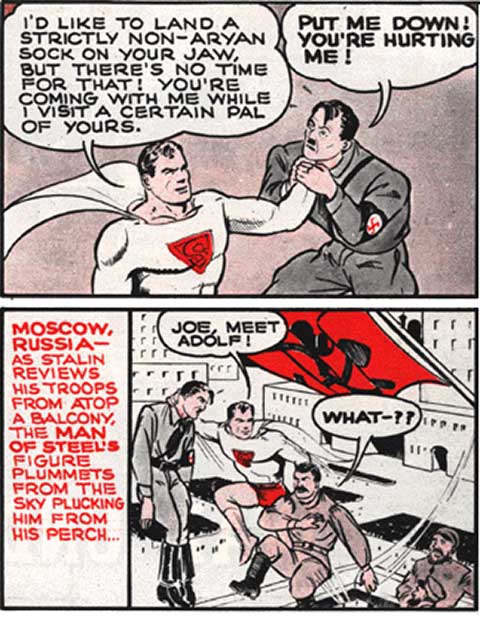

In this two-page comic, written by creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster for the magazine Look, Superman flew to Germany and picked up Adolf Hitler by the collar and then proceeded to do the same with ‘Joe’ Stalin in Moscow (Russia wasn’t an ally of the U.S. at the time). Finally, he delivered the two of them to the League of Nations in Geneva.

While holding a diminutive and comically helpless Hitler aloft in the air, Superman showed characteristic restraint in not brutalising the villain who was so obviously physically mismatched and said, “I’d like to land a strictly non-Aryan sock on your jaw. But there’s no time for that.” For the second-generation Jewish immigrants Siegel and Shuster, Superman—also an immigrant trying to ‘become American’—was the perfect medium with which they could express the impotent rage that Hitler’s brutalities in Europe had led to.

More than 70 years later, in Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel, Superman is no longer a relatively new figure. He has developed into a cultural icon, at once synonymous with American culture and a paragon of American virtues. For decades, he has flown relentlessly, a big, colourful signifier of what it meant to be American.

What has always shown through, in each of his reincarnations through the years, is that Superman is by definition a really nice guy. Umberto Eco, in his exploration titled The Myth of Superman, noted that in spite of being gifted with such powers that “he could actually take over the government, defeat the army or alter the equilibrium of planetary politics”, Superman chooses to be “profoundly kind, moral, faithful to human and natural laws” and “uses his powers only to the end of good”.

His superpowers render him virtually unstoppable, but in a way it makes sense. Societies have always had a fascination with mythological individuals with such incredible abilities who would, after a fashion, represent a certain perfection of qualities. In an industrial society, where man is a statistic and his own decision-making facilities are limited, individual strength, as Eco points out, “is left abased when confronted with the strength of machines” and as a result the “positive hero must embody to an unthinkable degree the power demands that the average citizen nurtures but cannot satisfy”.

By striving towards the elimination of the enemies of America, Superman—who is almost perfectly good and has the most defined moral compass among all superheroes—laid down a clear pattern for American readers. He, along with other superheroes, laid down clear ideological beliefs that were American and hence desirable. But while Superman is still as clearly a representative of American values and ideologies, the Superman seen in Zack Synder’s creation is markedly different from his predecessors. The traditional bright ‘S’ printed boldly on Superman’s chest that represented his ‘Super’-ness and consequently the ‘Super’-ness of all that he represents, has been replaced by a dimmer, grittier ‘S’ that is now also representative of hope.

In Man of Steel, by shifting the focus to the essential human conflicts faced by the superhero, Snyder automatically draws the viewer closer to his character through a process of self-identification. While previously Superman was what people hoped for, now hope itself has become one of the things that Superman—and by definition, America—signifies.

In order to understand this preoccupation with hope, I think it’s important to note the recent resurgence of comic book film franchises in the popular imagination (and box office earnings) in context of the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Centre. Slavoj Žižek in his venomous essay Welcome to the Desert of The Real, notes that the W.T.C. bombings replayed a scene that most American film viewers, especially readers of comic books, were already familiar with: “The land and the shots we saw of the collapsing towers couldn’t but remind us of the most breathtaking scenes in the catastrophe big productions”. Žižek argues that the intense awareness that individuals feel in a capitalist, consumerist society of living in an “insulated artificial universe” generates a constant “notion that an ominous agent is threatening us all the time with total destruction”.

This fantasy is played out in each and every episode of a Superman comic. It’s this very situation—where the object of fantasy is the destruction of America—that is depicted in every Superman film. Monstrous creatures, villainous aliens are plotting deviously to destroy America, but Superman—the protector of America—saves them. To summarise, the very point of Superman is to save America from destruction or alternatively reiterate the invincibility of American virtues and the capitalist society so long as the myth of Superman persists.

But if 9/11 brought home the awareness that such acts of destruction and terror actually existed outside the safe realm of fantasy, it also made Superman’s carefully constructed dialectic of good and bad more vulnerable. Further, the war on terror and the subsequent bombing of Afghanistan, a country that has already been reduced to rubble, only served to underscore the increasing impotency of the values that Superman had championed. The financial recession and the weakening of the American economy was the next nail in the bright, ‘boy-scout’ Superman’s coffin.

Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel.

Zack Snyder’s vision of Superman in Man of Steel is weighed down by these concerns. By revisiting the origin story of Superman, he is in fact offering to reimagine Superman’s myth, his values, and his enemies. Superman’s origin story is perhaps the best known story in the comic book universe, but by nature, questions pertaining to what has happened previously in the narrative are a rather hazy matter. In the words of Eco, each “narrator picks up the strand of the event again and again, as if he had forgotten to say something and wanted to add details to what has already been said”. Snyder is no exception, and in his narrative we see Superman rediscovering himself. The stress on this process of rediscovery allows Snyder to explore the Kryptonian’s humanity and outline the various qualities which ultimately make him worthy of being a symbol for America.

The focus, as noted by Time’s Richard Corliss, is not on Superman’s superhuman abilities (those are known), but his “roiling humanity”. In the post-9/11 world, the destruction that had previously been fantastical has been brought to the real world of Superman’s consumers, and this “roiling humanity” is, in essence, a reflection of the confused churning of all the values that had previously been held dear by Superman and his world. Superman’s own doubts about his abilities and what he should do with them parallel the doubts of the capitalist society in a post-9/11 world. It’s no longer possible to view the world in the cheery colours that clear dialectics between good and evil could allow, and the film is noticeably grittier.

Snyder’s Clark Kent—after the death of his adoptive father—travels across the world on a journey of self-discovery. He, unlike Bruce Wayne, doesn’t come from money, and works as a blue-collared worker in a variety of jobs, nonchalantly saving people along the way. Throughout this journey, Kent lives as a shadow, changes identities while dealing with his loss. He finally makes his way to an alien ship, where the preserved consciousness of his biological father Jor-El explains to him that he was sent to earth to give hope to humanity.

This plotline is hardly surprising, but the focus repeatedly remains on Superman’s humanity. General Zod—who in previous franchises has been represented as a villainous, bloodthirsty, and psychotic villain—is humanised to an extent. Zod reveals his desire to create a new Krypton, literally over the corpses of humanity; to create what he feels is a better world—a world where Clark Kent will truly belong and not exist as an outsider and an outcast. Clark Kent’s rejection of Zod’s plan, his eventual foiling of Zod’s colonisation attempt, and finally his annihilation of Zod (after yet another sequence which leads to the near destruction of an American city) truly underscores the new virtues that Superman/Kent embraces. He is no longer merely a Kryptonian stuck on earth. By killing Zod, he rejects Krypton for Earth—or more specifically, America.

That the focus is on Superman’s humanity has two important effects: firstly, it allows the viewer to identify with him to a larger extent, and secondly, and perhaps more importantly, Superman’s acceptance of his country as the place where he belongs (he later helps the American army with projects) underscores the idea that even in the dark and confused world of crumbling capitalist structures and declining American hegemony, the Man of Steel still flies with the country.

In a post-9/11 world, Superman no longer has the ideological clarity to boldly wear the bright yellow-and-red ‘S’ on his chest. He has become grittier and more self-conscious. And in a world finally coming to terms with its own deception, his role is not to champion virtues but to represent the virtue of hope.

Rot in heaven Garol! I think you and your writers are relating things unnecessarily. Man! Were you smoking ganja when you wrote this piece?

P.S.: You got some typos:

“In the post-9/11 word”

“in the in the catastrophe”

What makes you think I am not already rotting in hell? :D And thanks for pointing out the typos. Didn’t get time to go through it properly.