One day, back when thick rimmed glasses hadn’t “come back”, quite simply because they hadn’t left yet, Dave Brubeck set out to look for his mojo. This story has a happy ending: he found it soon afterwards.

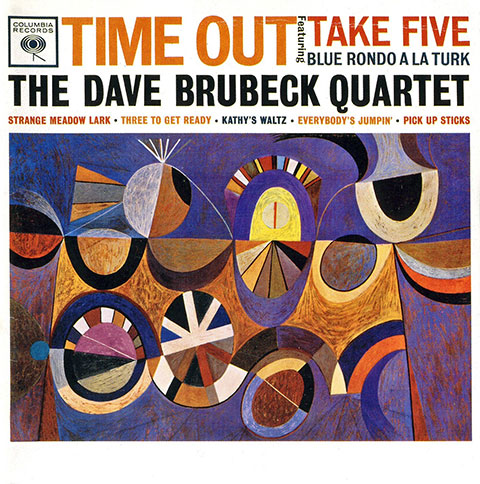

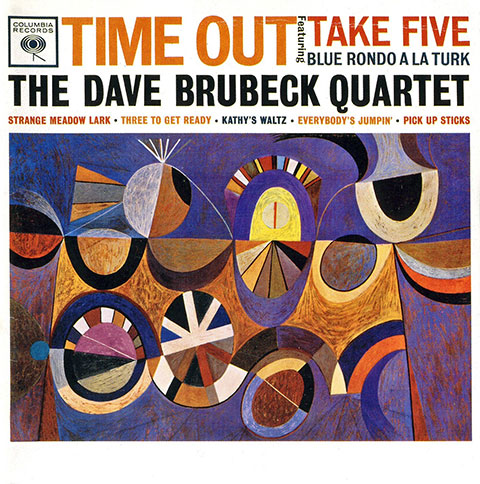

He and his Quartet cut Time Out in 1959, and if sunshine pop hookiness were a planet, and improvised jazz another (of a more metallic kind, maybe with two moons instead of one), then Time Out would be the first of many spaceships to traverse the complicated distance in between, and do it with all the good-natured grace you’d expect of the very gifted men who made it.

The Dave Brubeck Quartet is really the most cheerfully clever thing there is.

And don’t go mistaking this music for the silken charlatanry of Norah Jones and all her wretched kind: the stuff that has come to be known as “jazz-pop” is neither jazz nor pop; it’s just wet. The Quartet, on the other hand, are cerebral and disciplined, among the finest in their field. They bring to jazz a snappy tunefulness and an idiosyncratic way with groove that is wholly of their own invention, and it is a perennial problem with language that putting things this way makes them sound so stern, when the Dave Brubeck Quartet is really the most cheerfully clever thing there is.

Dave Brubeck passed on late last year, and, as when many old men die, this caused not much of a stir. The obituaries were suitably respectful, of a dignified, literate stripe in keeping with the bespectacled man in a suit who played the piano. Few papers ran much more than a short column, Facebook and Twitter didn’t erupt in eulogies; as an item of news, the small amount of traction it might have had was quickly eclipsed by Ravi Shankar’s own death within the week.

Put Dave Brubeck’s entire recorded output from end to end, and you’ll find a man above such mortal shortcomings as fatigue and creative burnout: his last full-length L.P. isn’t 10 years old (there are other appearances on record more recently still), and it is as characteristically well made as it is characteristically Brubeck. The marketplace might have doled out to it the tepid response it saves for artists considered to be “past their prime” (half a century ago, Time Out was the first jazz record to be a hit on a pop chart), but then, the marketplace can’t tell good from bad, and it certainly cannot tell a man whose every circuit is still sparking in his magical, brilliant, vital brain.

And this is what is best. Dave Brubeck was very alive until he wasn’t, and maybe that’s why his dying made scarcely a ripple: being alive is the opposite of turning into a relic, and the passing of a relic might be a national event, but a death is just a death.